Team:NYMU-Taipei/Design/The CHAMP Design

From 2011.igem.org

(Created page with "==What is the CHAMP design== CHAMP, the computed helical anti-membrane protein, is one of the computational and genetic methods available to engineer antibody-like molecules that...")

Newer edit →

Revision as of 13:31, 8 September 2011

What is the CHAMP design

CHAMP, the computed helical anti-membrane protein, is one of the computational and genetic methods available to engineer antibody-like molecules that target the water-soluble regions of tansmembrane (TM) proteins.

Cited form Supporting Online Material for Computational Design of Peptides That Target Transmembrane Helices Published 30 March 2007, Science 315, 1817 (2007)

Why we use the CHAMP design

Transmembrane helices usually play essential roles in biological processes. However, companion methods to target the TM regions are lacking. The CHAMP design of TM helices that specifically recognize membrane proteins would advance our understanding of sequence-specific recognition in membranes and simultaneously would provide new approaches to modulate protein-protein interactions in membranes.

Since we already known the initial purpose of the CHAMP design, now we want to let the CHAMP design play a pivotal role in our project to modulate the protein-protein interactions in membranes. But why exactly is the CHAMP design so important in our iGEM project this year?

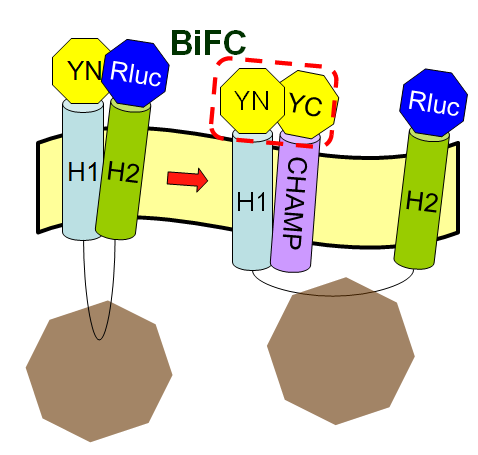

The CHAMP peptide design is the crucial part of this year's Wireless neuro-stimulator (back to Project Introduction) is because we hope that the designed peptide can inhibit the tight interaction between two helices of membrane protein Mms13. And we can then successfully use machanical force to change the conformation of Mms13 to induce the BRET phenomenon. If we don't have the target peptides, the two helices of Mms13 will tightly "stick" together and we can foresee the results with the fundamental knowledge of physics that the magnetic force applied to the bacteria wouldn't make any change to the conformation of the transmembrane protein, Mms13.

How to design the CHAMP peptides

We follow the methods published in 30 March 2007, Science 315, 1817 (2007) Supporting Online Material for Computational Design of Peptides That Target Transmembrane Helices and Understanding Membrane Proteins. How to Design Inhibitors of Transmembrane Protein–Protein Interactions. We try to follow the steps in the papers. However, because of the limited sources we found, we had a little adjusments by using different programs or softwares to approach our final CHAMP design. We also read some references-Helix–helix interaction patterns in membrane proteins and Interaction and conformational dynamics of membrane-spanning protein helices to give us more knowledge in protein-protein interaction in transmembrane domain and help us during the progress of designing our CHAMP design.

Mambrane peptide design

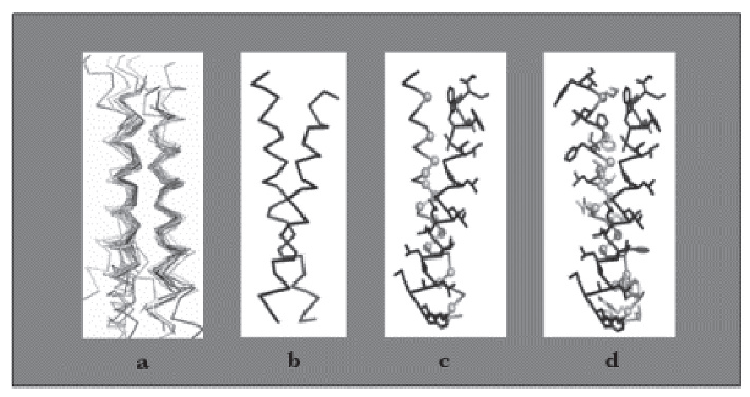

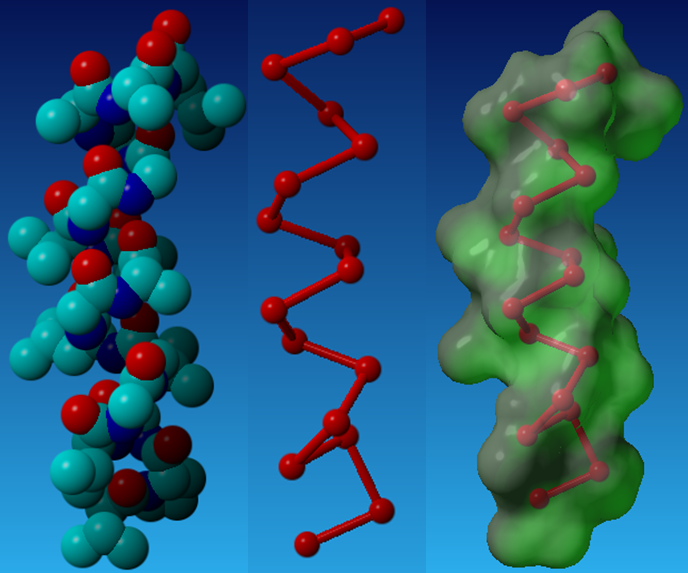

Recently, TM helical peptides that can bind to targets with high specificity and affinity have been designed de novo (Yin et al. 2007). The method consists of four steps: (1) selection of a helical-pair structural motif based on sequence; (2) selection of a nativelike helical-pair backbone within the chosen structural motif; (3) threading the sequence of the targeted TM helix onto one of the two helices of the selected pair; and (4) selection of the amino acid sequence of the designed peptide helix with a side chain repacking algorithm.

Above is the Design process for peptides that bind to transmembrane proteins.

a. Superimposed helicalpair backbones of one structural motif.

b. Selected backbone.

c. Target structure is threaded onto one helix (front helix), positions for repacking are selected on the other helix. Repacked positions are highlighted in light gray with spheres on Cα.

d. The designed helix (farther back) is repacked to have good van der Waals contacts with the target helix. Repacked positions shown in light gray with spheres on Cα.

(Cited from Understanding Membrane Proteins. How to Design Inhibitors of Transmembrane Protein–Protein Interactions)

We will introduce what we do according to those four steps above in detail in the following paragraphs.

Selection of a helical-pair structural motif based on sequence

First, determine the domains of Mms13's amino acid sequence

The full sequence of Mms13 is (A.A.) MPFHLAPYLAKSVPGVGVLGALVGGAAALAKNVRLLKEKRITNTEAAIDTGKETVGAGLATALSAVAATAVGGGLVVSLGTALVAGVAAKYAWDRGVDLVEKELNRGKAANGASDEDILRDELA.

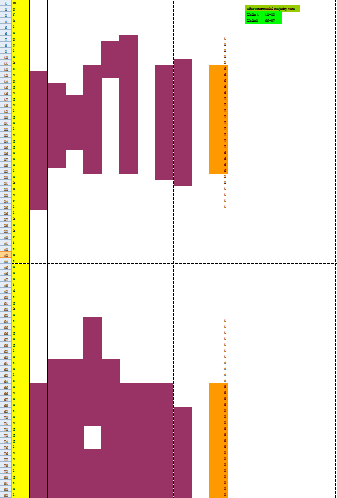

Because the protein, Mms13's structure is not 100% defined and known. We use several online prediction program to specify the domains of Mms13 using amino acid sequences. The prediction programs we use include sosui, DAS(low cut-off), DAS(high cut-off), TMHMM, PredictProtein, TMpred, HMMTOP, MEMSAT-SVM, TopPred. We then merged all the results using the cross-model majority vote and get the two helices of Mms13-Helix 1:a.a.12~29 and Helix2:a.a.65~87.

Below is part of the results of majority vote:

Below is the whole results of majority vote:

Second, selection of a helical-pair structural motif based on sequence

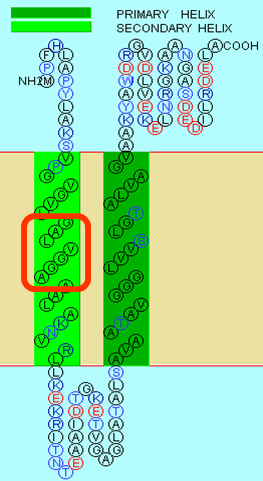

We choose the TM helix which have a G-X3-G sequence motif. GxxxG motifs exist in many TMDs and can induce their interaction. The contribution of GxxxG to an interface is apparently driven by a complex mixture of attractive forces and entropic factors (MacKenzie and Engelman 1998). It has been suggested that it leads to formation of a flat helix surface that maximizes van der Waal’s interactions and that the loss of side-chain entropy upon association is minimal for Gly (Russ and Engelman 2000). Moreover, the Gly residues reduce the distance between the helix axes and thus may facilitate hydrogen bond formation between their Cα-hydrogens and the backbone carbonyl of the partner helix (Senes et al. 2001a). After we search along the helices of Mms13, we found the critical G-X3-G sequence motifs on helix1 of the Mms13(Picture shown below).

Selection of a nativelike helical-pair backbone within the chosen structural motif

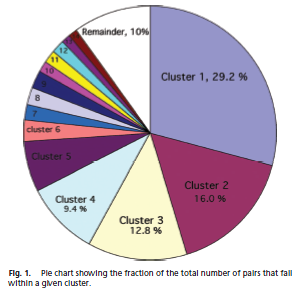

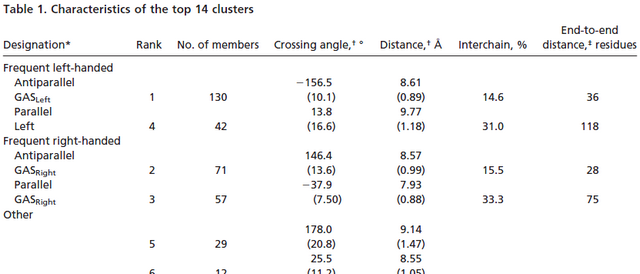

After we found the G-X3-G motif on Mms13 helix1, we have to select a nativelike helical-pair backbone as the templates of our CHAMP design. We study Helix-packing motifs in membrane proteins as the reference and follow the instructions to select the template cluster of our CHAMP design. In this paper, a library of 445 helical pairs from 31 proteins were clustered into groups based on their three-dimensional similarity. Different clusters have specific features and also show varying degrees of homogeneity. Because the helices of Mms13 are antiparallel and there's some traits of right-handed crossing angle in helix1 (ex. The helix1 of Mms13 have small residues at the helix–helix interface, and they are spaced at four-residue intervals just as in the right-handed antiparallel GASRight motif. However, in the left-handed antiparallel GASLeft motif instead have four-residue, the seven-residue spacing is observed in the cluster.) Due to those evidence we found in helix 1 of Mms13, finally, we choose cluster 2-the antiparallel GASRight cluster as our template candidates.

Below in the left is the pie chart showing the fraction of the total number of pairs that fall within a given cluster; in the right is one part of the Table 1. Characteristics of the top 14 clusters in Helix-packing motifs in membrane proteins.

However, after we select one cluster of our CHAMP design, we still have 71 candidates in cluster 2 for us to choose. We have to minimize the number of the possible candidates. Because ranking the structures based on calculated energies was difficult(We had no consistent baseline by which to compare

structures arising from templates of different lengths), the final rank was based on the uniformity of packing, which was assessed by finding structures with the minimal number of inter-atomic contacts that are closer than 1.0 Å from the expected van der Waals minimum distance (this is particularly important because of the linear dampening of the Lennard-Jones potential). So we submitted the sequence of Mms13 and got the predicted van der Waals minimum distance between two helices, and the result is 10 Å. After we got the result, we deselected the candidates in the cluster whose interhelical distance is out of the range of +/- 1.0 Å compared to 10 Å. And then, the remain candidates was minimized to only 27 candidates.

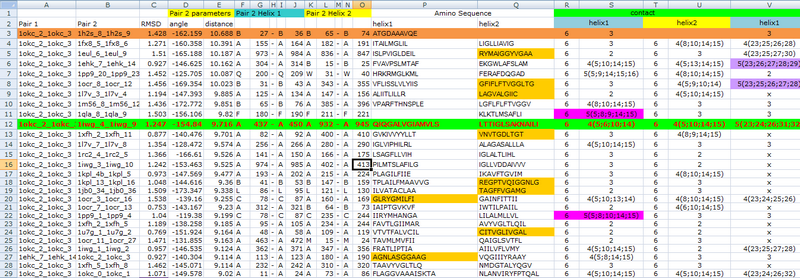

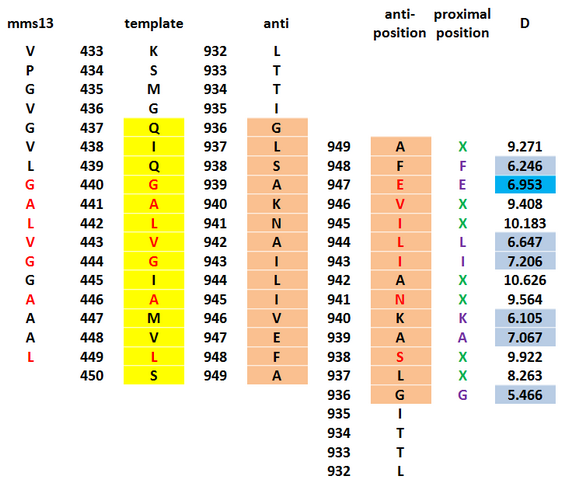

To get the most precise templates of our CHAMP design, we use the online program-TMhit(Lo A., Chiu Y.Y., Rødland E.A., Lyu P.C., Sung T.Y., and Hsu W.L. (2009) Predicting helix-helix interactions from residue contacts in membrane proteins, Bioinformatics (2009) 25: 996-1003. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp114), which is a method for inferring helix-helix interactions from residue contact prediction in transmembrane (TM) proteins. We select the best template pair by finding the templates whose one helix has the most residue contacts with Mms13 helix1 and whose sequence of another helix have the most residue alignments with Mms13. After all the exhausted compare progress, we choose protein 1iwg: A437-A450 and A932-A945 as the template pair of our CHAMP design. Below is part of data during the the exhausted compare progress of choosing the final candidate.

Threading the sequence of the targeted TM helix onto one of the two helices of the selected pair

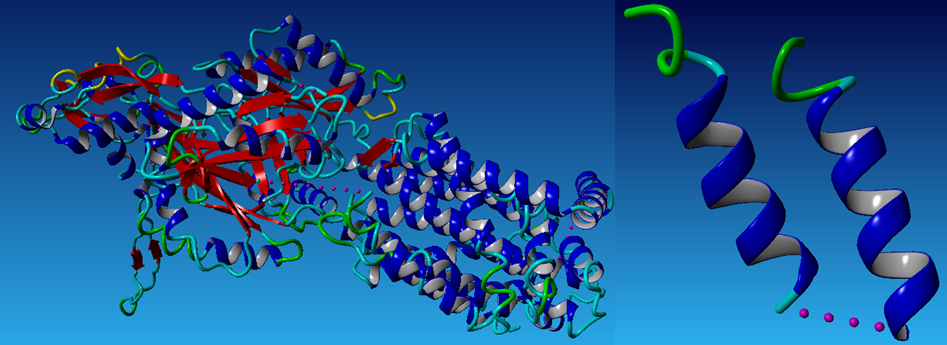

We use the online program-ProtMod-Protein Structure Modeling-Alignment to do the first time repacking to get the pdb file of the result Mms13 structure aligned with the helix of the chosen template-1iwg: A437-A450. Below (1)is the aligned Mms13 and (2)in the left is a whole protein of 1iwg; in the right is the selected template pairs: 1iwg: A437-A450 and A932-A945. The pictures are graphed by a molecular-graphics, -modeling and -simulation program -YASARA(Prof. Dr. Gregor Högenauer, Prof. Dr. Günther Koraimann, Prof. Dr. Andreas Kungl, Prof. Dr. Gert Vriend)

(1)

(2)

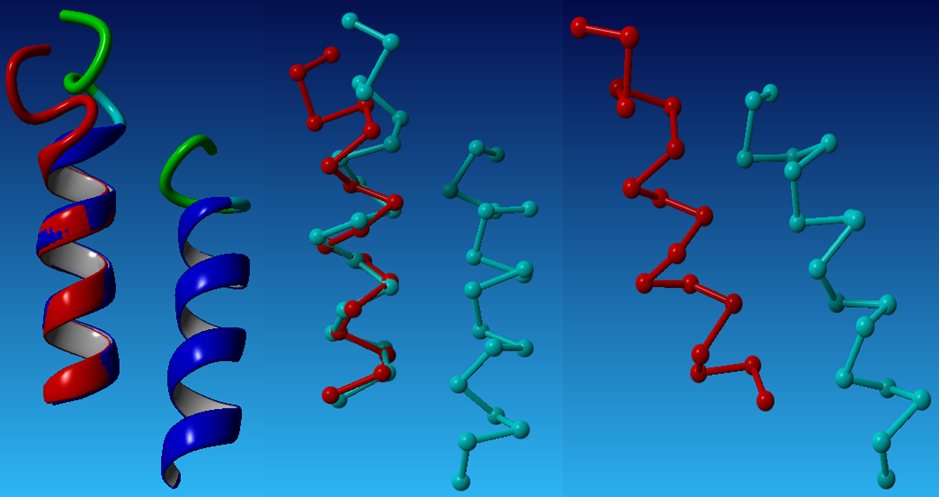

After we had the materials:the aligned Mms13 and the selected template pairs-1iwg: A437-A450 and A932-A945, we then started to thread the sequence of the targeted TM helix onto one of the two helices of the selected pair. The alignment for the threading was determined by matching the locations of the glycines in the G-X3-G motif of Mms13 helix1 to the glycines in the G-X3-G motif of the template structure. The backbones of the complex were then minimized to remove clashes with the threaded Mms13 sequence. The result after threading is graphed below.

Selection of the amino acid sequence of the designed peptide helix with a side chain repacking algorithm

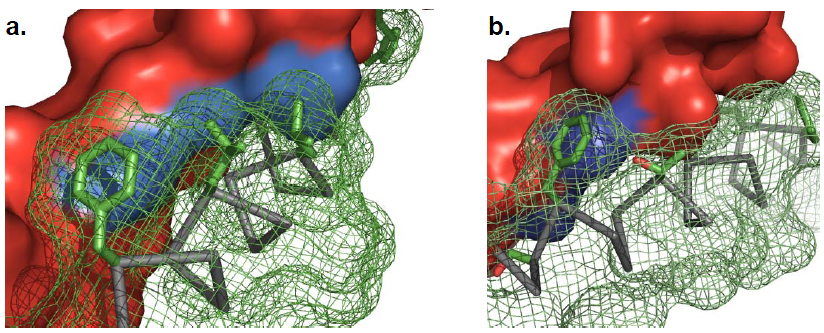

After threading, we then give a second stage repacking of the minimized structure and select a candidate that showed a uniformly packed interior. First, we tried to find the proximal positions between the Mms13 and the CHAMP template. We use the program, YASARA to calculate the minimal interhelical distances and use the program, VMD to show the hydrophobic regions to specify the proximal positions. The results are shown below.

On the CHAMP anti-mms13 helix, seven proximal positions were selected for repacking based on their proximity to the mms13-threaded helix for anti-mms13. As for how we choose the residues of the proximal positions, we use .

Because the natural backbones that were used were positioned such that they had nativelike interhelical hydrogen bonding, hydrogen bonding did not need to be encoded in the potential energy function. The potential that was used was very simple and consisted of only two terms: a van der Waals term and a statistical depth-dependent potential (Senes et al. 2007) in lieu of a solvation term. The ability of the designed peptides to discriminate between similar targets testifies to the importance of the shape complementarity in membrane protein oligomerization. To illustrate the method, peptides were designed that specifically recognize the TM helices of two closely related integrins (αIIbβ3 and αvβ3). The affinity and

specificity of this design was verified using a large number of experimental methods.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer assays and analytical ultracentrifugation

in micelles demonstrated the affinities of the designed peptides for their

targets. A dominant negative ToxCAT assay in E. coli membranes established that

the designed peptides acted specifically on their targets to the exclusion of other

homologous proteins. Platelet assays and force spectroscopy demonstrated that the

designed peptides activated their targets in vivo. More work will be needed to verify

that this method can be used for a wider variety of protein targets, but it seems

likely that this method has many diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

"

"