Team:Cambridge/Project/In Vivo

From 2011.igem.org

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Template:Team:Cambridge/CAM_2011_TEMPLATE_HEAD}} | {{Template:Team:Cambridge/CAM_2011_TEMPLATE_HEAD}} | ||

| - | |||

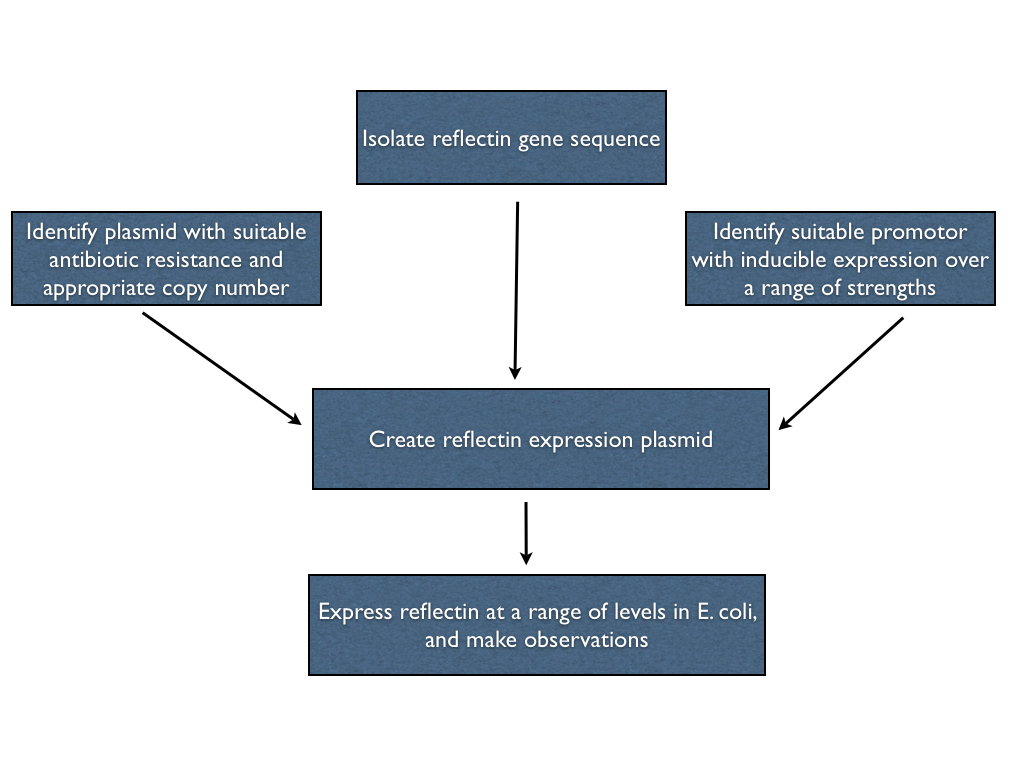

Our first objective was to try to express reflectin, in any shape or form, in E. coli. Ideally, we'd be able to express reflectin in the bacteria at a range of levels using a single construct, so we can both overexpress (for ''in vitro'' studies) or underexpress (to promote ''in vivo'' folding) straightforwardly. In order to do this, we had to create an expression plasmid for reflectin with which we could transform the bacterial cells. Hence, we had to isolate a reflectin gene sequence, choose a suitable promotor and join them on an appropriate backbone in order to engineer what we wanted. These steps are outlined below. | Our first objective was to try to express reflectin, in any shape or form, in E. coli. Ideally, we'd be able to express reflectin in the bacteria at a range of levels using a single construct, so we can both overexpress (for ''in vitro'' studies) or underexpress (to promote ''in vivo'' folding) straightforwardly. In order to do this, we had to create an expression plasmid for reflectin with which we could transform the bacterial cells. Hence, we had to isolate a reflectin gene sequence, choose a suitable promotor and join them on an appropriate backbone in order to engineer what we wanted. These steps are outlined below. | ||

[[File:camflow_1.jpg | centre | 600px | Objective One]] | [[File:camflow_1.jpg | centre | 600px | Objective One]] | ||

Revision as of 15:25, 10 August 2011

Our first objective was to try to express reflectin, in any shape or form, in E. coli. Ideally, we'd be able to express reflectin in the bacteria at a range of levels using a single construct, so we can both overexpress (for in vitro studies) or underexpress (to promote in vivo folding) straightforwardly. In order to do this, we had to create an expression plasmid for reflectin with which we could transform the bacterial cells. Hence, we had to isolate a reflectin gene sequence, choose a suitable promotor and join them on an appropriate backbone in order to engineer what we wanted. These steps are outlined below.

Contents |

Isolating the reflectin gene

This was more complicated than we initially expected. Our first idea was to attempt to clone reflectin genes from genomic DNA, extracted from the same squid specimens that we dissected for our [preliminary observations]. We started with a very crude genomic extraction protocol, but unfortunately we did not manage to successfully clone reflectin using this method (details of the experiment can be found [here]). We then attempted two cleaner genomic extraction protocols (described [here]), but unfortunately we remained unsuccessful. After some discussion with Dr. Wendy Goodson, a researcher who was one of the first to study reflectin, we found out that cloning from cephalopod genomic DNA is notoriously difficult, although the cause for this is not understood. She then very kindly offered to send us a quantity of cloning plasmids containing reflectin genes that she has worked with in the past; in this way we obtained genes for reflectin A1, A2 and 1B that had already been codon optimised for expression in E. coli. The amplification of these plasmids is described [here].

Selecting the promotor

Selecting the backbone

Creating the expression plasmid

Hopefully coming soon!

Expression in E. coli

Hopefully coming soon!

"

"