Team:Grinnell/Project

From 2011.igem.org

(→Biofilms) |

(→Biofilms) |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

Due to its extracellular structure, a biofilm can act as a protective barrier for associated cells against various adverse conditions and can aid in the communication between cells(Foley & Gilbert 1996). Cells within a biofilm are frequently found to be more resistant to antimicrobials compared to planktonic cells (Simões & Vieira 2009). Moreover, the EPS serves as a bridge between cells, promoting intercellular communication that may facilitate cells’ (or the biofilm's as a whole) adaptation to changing environment (Davis et al. 1998). | Due to its extracellular structure, a biofilm can act as a protective barrier for associated cells against various adverse conditions and can aid in the communication between cells(Foley & Gilbert 1996). Cells within a biofilm are frequently found to be more resistant to antimicrobials compared to planktonic cells (Simões & Vieira 2009). Moreover, the EPS serves as a bridge between cells, promoting intercellular communication that may facilitate cells’ (or the biofilm's as a whole) adaptation to changing environment (Davis et al. 1998). | ||

| - | |||

These traits make the elimination of biofilms a challenging concern in a wide range of fields, especially in the food, energy, and biomedical industries1. Pathogens such as <i>E. coli</i> O157:H7 and <i>Staphylococcus aureus</i> will contaminate food products, microorganisms in biofilms will catalyze chemical and biological reactions causing metal corrosion in pipelines and tanks, and biofilms reduce heat transfer efficacy if it becomes too thick1 (Mittelman, 1998). | These traits make the elimination of biofilms a challenging concern in a wide range of fields, especially in the food, energy, and biomedical industries1. Pathogens such as <i>E. coli</i> O157:H7 and <i>Staphylococcus aureus</i> will contaminate food products, microorganisms in biofilms will catalyze chemical and biological reactions causing metal corrosion in pipelines and tanks, and biofilms reduce heat transfer efficacy if it becomes too thick1 (Mittelman, 1998). | ||

Revision as of 04:57, 29 September 2011

Project

Project Overview

Biofilms are cells encased in a hydrated extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix that is composed of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids (Lu & Collins 2007). Biofilms act as a protective umbrella for their inhabitants against various adverse conditions and can aid in communication between cells (Foley & Gilbert 1996). Biofilms have recently become a concern in various fields, including health, food, and energy. The structure of biofilms make them difficult to remove once mature. By protecting the cells involved and facilitating horizontal gene transfer biofilms increase virulence of the incorporated bacteria.

Synthetic biologists are beginning to tackle the problem of biofilms, as evidenced by the number of iGEM teams interested in the degradation and inhibition of biofilms in recent years. These projects have been conducted using the workhorse of synthetic biology, E. coli, with a focus on finding ways to kill the bacteria in the biofilm before the biofilm is formed (inhibition) or by infiltrating the biofilm (degradation). Our team approached this problem differently in two ways: we aimed to exploit the rigorous type I secretion pathway of Caulobacter crescentus, and we sought to degrade the EPS rather than kill the involved cells.

We decided to utilize Caulobacter because it has many advatages over E. coli for our purposes. The first of these is the robust TypeI secretion system that Caulobacter uses to secret its paracrystalline S-layer protein, RsaA, which makes up 10-12% of manufactured protein in lab strain CB15N (a strain which is deficient in producing a holdfast). Caulobacter is an aquatic bacterium and it grows well in low-nutrient environments. Like E. coli, Caulobacter is gram-negative and has had its genome sequenced, however Caulobacter is safer for use around humans as it produces 100 times less endotoxin than E. coli, and is unable to survive in a human body. To exploit the secretion pathway, we planned to attach the C-terminal secretion tag from RsaA to a biofilm inhibiting or degrading protein. This allows our system to produce and secrete large quantities of enzyme that are easy to isolate because there is no cell lysis that is necessary.

For the biofilm degrading enzymes that we chose to have Caulobacter secrete, we focused our efforts on a serine protease, Esp (Iwase et al. 2010), from Staphylococcus epidermidis, and a hydrolase, DspB (Kaplan 2003), from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans that have both been shown to degrade biofilms.

The general goals of our project were: 1) to introduce Caulobacter as another potential chassis for synthetic biology, especially in environmental and biomedical-related fields; 2) to create a toolbox of biobrick parts that enable easy exploitation of Caulobacter's typeI secretion system for any protein of interest through fusion to the C-terminal secretion tag; 3) and to develop a system for degrading biofilms by targeting the EPS.

Background

DspB Esp

Esp

Caulobacter crecentus and Type I secretion

Caulobacter crescentus is an aquatic gram-negative bacterium. It is widely used as a model organism for studying cell cycle, cell division and cell differentiation. Caulobacter divides asymmetrically to produce two morphologically different progeny, a swarmer and a stalked daughter cell (Laub et al. 2007). Only the stalked Caulobacter cells can initiate chromosome replication. The swarmer cells differentiate into stalked cells after a period of motility. The stalked cells produce an extremely strong polar adhesive called the holdfast (Toh et al. 2008) which can serve as a biofilm initiator. The Caulobacter strain we used (CB15N) is deficient in the gene that is responsible for producing the holdfast.

In the wild, Caulobacter is found in freshwater lakes and streams, where low nutrient conditions are common. However, Caulobacter cells are well equipped with various environmental sensors and transporters so that they are able to survive. For example, Caulobacter has many more TonB-dependent receptors than most bacteria, which are accountable for gathering carbohydrates from a variety of sources (Ryan et. al, 2010). Caulobacter is even capable of halting cell cycle progression in extreme dilute aquatic environment (Laub et al. 2007).

One feature of Caulobacter that is often overlooked is its surface layer. The S-layer of Caulobacter is composed of a single protein—RsaA, which is secreted and assembled into a hexagonal crystalline array that covers the organism. RsaA provides Caulobacter a measure of protection for the cell from attacking agents such as proteases, viruses and parasitic bacteria (Nomellini et al. 2004). RsaA makes up approximately 10-12% of the total cell protein production. The synthesis of RsaA occurs without need for induction and the protein is produced continuously throughout the life cycle (Nomellini et al. 2004). The secretion system for RsaA is also well studied: secretion is ATP-driven and considered a type I secretion pathway given the fact that the C-terminal secretion signal is not cleaved off after secretion (Awram & Smit 1998). The secretion signal has been shown to be within the C-terminal 82 amino acids of RsaA (Bingle, Nomellini and Smit 2000), and proteins as large as RsaA (98kDa, 1025 amino acids) (Gilchrist, Fisher and Smit 1992) can pass through the cell membrane successfully.

Thus, the reasons we chose Caulobacter as our chassis organism can be summarized as follows: Caulobacters secrete recombinant proteins using the Type I secretion system, not the General Secretory Pathway (GSP), which is more common. The bacteria are obligate aerobes and grow to high densities in minimal media, up to OD 25-30. They do not secret other proteins and have a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that has surprisingly low endotoxin potential. They are easily manipulated in lab and have a sequenced genome. And the yields are usually high for heterologous protein secretion (Nomellini et al. 2004).

Biofilms

Biofilms are a unique community of usually heterogeneous microorganisms that readily attach to rough and hydrophobic surfaces1. They are composed of cells encased in a hydrated extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix that is composed of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids(Lu & Collins 2007).

Due to its extracellular structure, a biofilm can act as a protective barrier for associated cells against various adverse conditions and can aid in the communication between cells(Foley & Gilbert 1996). Cells within a biofilm are frequently found to be more resistant to antimicrobials compared to planktonic cells (Simões & Vieira 2009). Moreover, the EPS serves as a bridge between cells, promoting intercellular communication that may facilitate cells’ (or the biofilm's as a whole) adaptation to changing environment (Davis et al. 1998).

These traits make the elimination of biofilms a challenging concern in a wide range of fields, especially in the food, energy, and biomedical industries1. Pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7 and Staphylococcus aureus will contaminate food products, microorganisms in biofilms will catalyze chemical and biological reactions causing metal corrosion in pipelines and tanks, and biofilms reduce heat transfer efficacy if it becomes too thick1 (Mittelman, 1998).

The Experiments

Constructs

Since Caulobacter crescentus has a G/C rich genome (over 60%) and both esp and dspB coding regions are G/C poor, we had the sequences codon optimized for expression in Caulobacter.

We were also interested to see the difference of gene expression in Caulobacter between the wild type and optimized genes, and we wanted to make the wild type esp gene available for other synthetic biologists to use. Therefore, we acquired the wild type esp gene from Staphylococcus epidermidis by PCR. We obtained our wild type dspB gene from the University of British Columbia.

The promoters we used were Pxyl, PrsaA and BBa_K081005, all functioning at a relatively high efficiency in both E. coli and Caulobacter. Pxyl is a xylose-inducible promoter that originates from Caulobacter; PrsaA is a strong constitutive promoter also native to Caulobacter that is responsible for initiating transcription of rsaA; BBa_K081005 is a strong constitutive promoter that was designed by the 2008 iGEM team from the University of Pavia.

We knew from previously published reports that as few as 80 amino acids of the C-terminal end of RsaA function as a secretion tag for heterologous proteins. However, a larger secretion signal can increase the efficiency of secreting heterologous proteins, so we cloned the C-terminal 120 amino acids from Caulobacter strain CB15N. We engineered the following seven constructs:

| PrsaA | Pxyl | BBa_K081005 | |

| dspB (optimized) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| esp (optimized) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| esp (WT) | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ |

All of the initial cloning was done in E. coli and after each construct was completed, we transferred the biobrick part from pSB1C3 plasmid to pMR10, which replicates in Caulobacter crescentus and E. coli at a low copy number. The pMR10 constructs were transferred into Caulobacter by conjugation.

One issue that gave us a hard time in the beginning of our project was that when we made the esp or dspB fusion with the rsaA C-terminal secretion signal using the standard biobrick prefix and suffix a stop codon was formed in the scar between the two genes that terminated the expression before the RsaA C-terminal secretion signal. Later, we solved the issue by modifying the suffix of the upstream gene and the prefix of the downstream gene so that the stop codon would no longer be in frame.

Data & Results

The following results show that most of our chimeric proteins were expressed and secreted from Caulobacter and had significantly greater activity against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms than the WT Caulobacter strain.

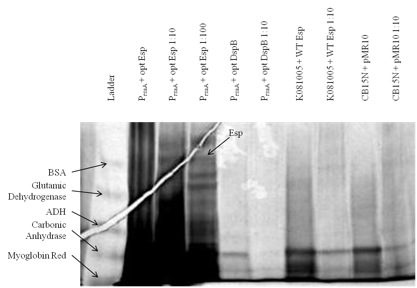

Figure 1. Expression and secretion of chimeric proteins from Caulobacter. We cultured each of our Caulobacter secretion strains and collected the supernatants from equal numbers of cells. The proteins in the supernatants were precipitated with TCA, run on a 6-18% polyacrylamide gel, and silver stained. Results show that proteins of the expected size were secreted from PrsaA with chimeric Esp/RsaA C-terminal construct. However, even though we used gradient gel and silver staining, bands did not appear easily: only those constructs that presumably had a high yield of heterologous protein had bands corresponding to the desired biofilm inhibitor protein.

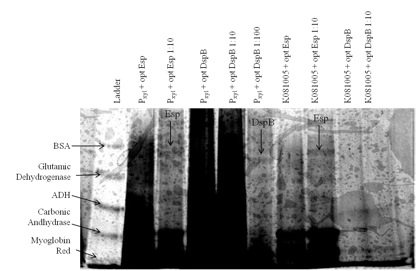

Figure 2. Expression and secretion of chimeric proteins from Caulobacter. We cultured each of our Caulobacter secretion strains and collected the supernatants from equal numbers of cells. The proteins in the supernatants were precipitated with TCA, run on a 6-18% polyacrylamide gel, and silver stained. Results show that proteins of the expected size were secreted from the following strains: both DspB and Esp constructs with Pxyl inducible promoter and chimeric Esp with promoter [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K081005 BBa_K081005].

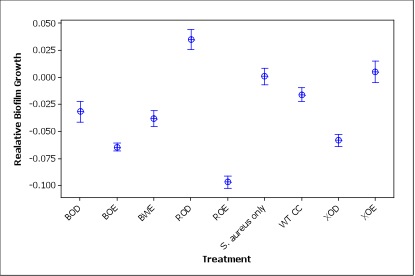

Figure 3. Relative S. aureus biofilm growth after treatment with different engineered Caulobacter strains (three letters abbreviation for constructs: B for BBa_K081005, R for PrsaA, X for Pxyl, O for optimized, W for wild type, E for Esp, D for DspB, and CC for WT Caulobacter crescentus). Relative biofilm growth is calculated by subtracting the ODmean of S. aureus only treatment from the OD of each well.

Compared to S. aureus only treatment, most of the other treatments had significantly lower biofilm growth (p<0.001) except XOE construct (p=0.743) and wild type Caulobacter (p=0.085) treatments show no significant differences from the S. aureus treatment. Notably, the ROD construct induced S. aureus biofilm formation to some extent, which is worth further investigation. The failure of XOE is explainable: xylose, the inducer of the Pxyl promoter of this construct, is usually consumed by the cells after 4h but we incubated cell cultures with xylose for more than 24 h. Therefore, Esp might have been produced by the Caulobacter strain in the first several hours but then xylose was used up and therefore new Esp was not being produced during the biofilm inhibiting step.

The inhibition effect on biofilm growth of different proteins, the efficiency of different promoters and the expression level of wild type esp and optimized esp in Caulobacter were also compared among constructs.

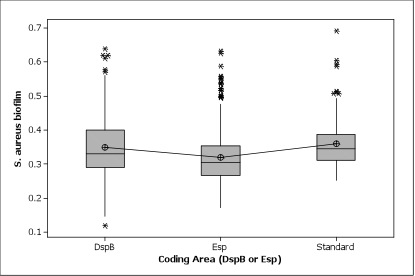

Figure 4. Here the standard group was composed of S. aureus only and WT groups. Both DspB and Esp can inhibit the biofilm growth. Though not statistically significant, the biofilm assay data showed a general trend that Esp, which is known to target for S. aureus biofilm specifically, has a better inhibition effect than DspB, which is generally targeting most biofilms.

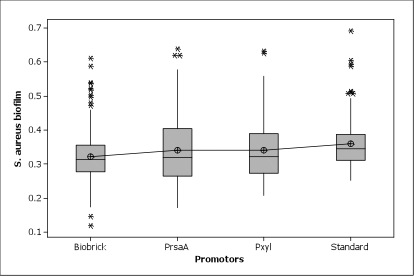

Figure 5. All promoters were working great in Caulobacter. No significant difference among three promoters were shown.

"

"