Team:Freiburg/Description

From 2011.igem.org

(→References) |

(→Bacterial artificial chromosome) |

||

| Line 267: | Line 267: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| - | References | + | References: |

| - | + | ||

O'Connor M, Peifer M, Bender W (1989). "Construction of large DNA segments in Escherichia coli". Science 244 (4910): 1307–1312. | O'Connor M, Peifer M, Bender W (1989). "Construction of large DNA segments in Escherichia coli". Science 244 (4910): 1307–1312. | ||

Revision as of 00:02, 22 September 2011

Contents |

Precipitator

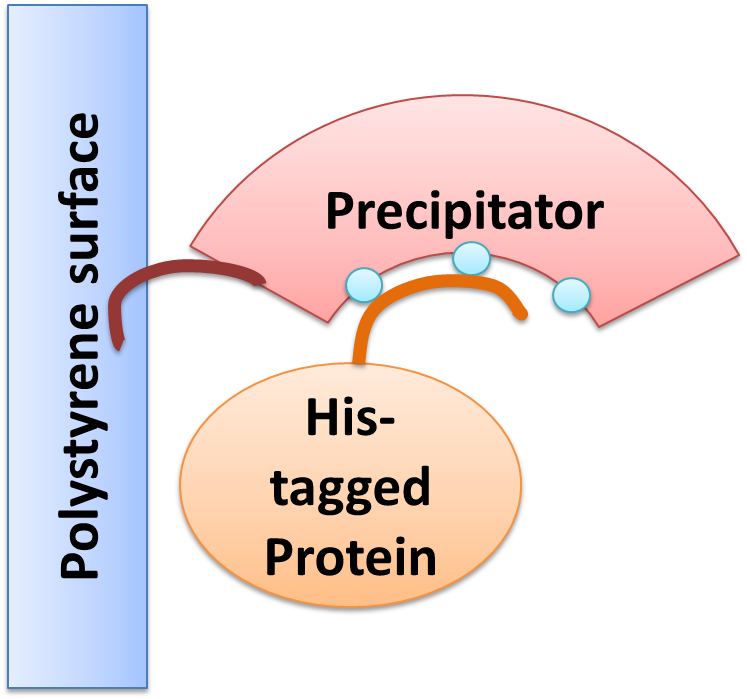

Precipitator binding a polystyrene surface with the plastic binding domain and a His-tagged Protein via Nickel ions |

The Concept

We created a cellular, self-replicating purification device for His-tagged proteins. It is a completely artificial fusion protein, which consists of a repeating LRRNT motif domain, coordinating Ni2+ Ions on its surface capped on N and C terminal ends by a hagfish sequence of a similar LRRNT motif. We named this construct “THE PRECIPITATOR”. A second domain, a short hydrophobic peptide stretch, binds a polystyrene surface, called the plastic binding domain. After expression of the Precipitator in a light inducible E. coli strain, the cells are lysed and the lysate is taken up with a serological pipette, in preparation of the actual protein purification steps. The underlying mechanism is comparable to Ni-NTA columns. Our Precipitator protein binds on the surface of the pipette, presenting the chelated Nickel ions. Free coordination sites of the Nickel ions are exposed, so that a His-tagged protein can attach to them. Cells expressing a His-tagged protein can be dissolved by the heat inducible lysis-device. Subsequently, when the lysate is taken up with a serological pipette coated with the Precipitator protein, the His-tagged proteins bind to it. Cell debris is then washed off, while the His-tagged protein stays and is eluted afterwards, in the same fashion as done in Ni-NTA columns with imidazole solutions, increasing in concentration. The His-tagged protein is finally captured in a distinct fraction.

Part design

The Precipitator [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K608406 BBa_K608406] protein is made of an artificial Leucine Rich Repeat (LRR) as the middle part of our own design, capped by C and N-terminal hagfish domain fragments. This part is one version of three different designed to bind nickel by histidines, grouped together pointing away from the horseshoe shaped protein. Please see modeling for more details

Bacterial LRR Consensus of the central LRR fragment:

LxxLxLxxNxLxxLPxxLPxx

| Protein sequence CPSRCSCSGTEIRCNSKGLTSVPTGIPSS LTQLTKSNNHLHSLPDNLPAS LEVLDVSNNHLHSLPDNLPAS LEVLDVSNNHLHSLPDNLPAS LEVLDVSNNHLHSLPDNLPAS LEVLDVSNNHLHSLPDNLPAS LEVLDVSNNHLHSLPDNLPAS LKELALDTNQLKSVPDGIFDR LTSLQKIWLHTNPWDCSCPRIDY LSRWLNKNSQKEQGSAKCSGSGKPVRSIICP |

|

|

Colorcode (same in the sequence and video) | |

This protein can be used to complex Nickel or Cobalt. Histidines are positioned in such a way, that they can coordinate the ions from two to four orthogonally oriented directions. Free binding sites of the ions are then exposed, so that a His-tagged protein can attach to them. This protein can be used to complex up to 4 nickel or cobalt ions. The underlying design of the protein is of a particular interest, too. LRRs are highly conserved motifs throughout evolution. They appear in all kingdoms of life in almost every thinkable role (ligases, receptors, toxins etc.). Their core is highly conserved and provides a very stable backbone, while the non-conserved aminoacids are almost freely interchangeable. Here we investigated an optimal set of non-conserved aminoacids by analysing large sets of similar proteins and databases. You can use this piece of work as a template to design your own protein and give it any function you like, by simply interchanging aminoacids and fusing other domains on the N or C termini. To guarantee proper folding and to shield off the hydrophobic core, a well studied fragment of an LRR protein coming from hagfish was used. The efficiency of this technique was proven before (Schmidt 2010). To find out the most likely folding, we designed many different protein sequences, trying out a variety of sets of non coding aminoacids for the LRR and submitted these to the I-TASSER structure prediction

We only submitted one of the three versions to the registry to reduce redundancy. Please contact us for any questions.

Plastic binding domain

One of the issues of our project „lab in a cell“ was to use endogenous proteins produced by the cell itself for specific purification and hereby to replace expensive columns. The „precipitator“ designed by our team contains a protein binding domain which complexes nickel and thus enables the binding of His-tagged proteins. After cell lysis the “precipitator” is freely dissolved in the cell lysate. To be able to isolate the “precipitator”-His-tagged-protein-complex from the other cell components it has to be immobilized by another protein domain. The part we designed for this function is the so-called plastic binding domain.

During routine phage display of random peptide libraries, phages were found that bound directly to the plastic surface of the used plastic micro titer plates. The number of plastic binding phages obtained during the phage display experiments depended on the saturation of the plastic micro titer plates with target protein for the antibody-binding phages and could be reduced by the use of blocking proteins as BSA or non-fat milk. Plastic binding phages were resistant to washing steps with PBS alone as well as to PBS in combination with BSA or non-fat dry milk. It was shown that plastic binding phages were even more difficult to recover by acid elution than the “normal” antibody binding phages (Adey et al., 1995).

The binding strength of the plastic binding protein was best on polystyrene plastic surfaces and also observed on PVC-plates (Adey et al., 1995).

The mechanisms by which the phage surface proteins bind to plastic are not well understood. The plastic binding amino acid sequences showed no obvious sequence similarity but where generally enriched by Tyr and Trp residues and are completely devoid of Cys residues. It is possible that the binding comes off non-specific hydrophobic interactions due to partial denaturation of the protein (Cantanero et al., 1980) and potentially due to interactions of the Tyr and Trp residues with the aromatic moieties of the polystyrene plastic surface of micro titer plates.

As well as high hydrophobicity does not necessarily imply plastic binding quality (Menendez et al., 2005) the observed plastic binding phages showed hydrophobic peptide sequences on their surfaces. Expressing such hydrophobic proteins in our host organism E. coli can lead to problems with inclusion bodies or decreased vitality up to cell death.

During our experiments we couldn’t obtain any clones containing both the gene for the plastic binding protein and a constitutive promoter-RBS-construct. We finally succeeded in expressing the plastic binding domain using an inducible promoter. To test the plastic binding domain and get data for our modeling we hereby used an IPTG-inducible promoter. In our completed “Lab in a cell” model the plastic binding domain, as a part of the “precipitator” would be expressed by one of our light inducible promoters.

Green light receptor

Sometimes a regulated and coordinated gene expression and therefore protein production is needed.

We decided to use light-controlled gene expression, because light is everywhere and always available.

The green light receptor is a light-sensing system from the cyanobactrium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803.

It consists of three parts interacting with each other in order to start regulated gene expression.

These parts are the following:

The main receptor is CcaS(1), a cyanobacteriochrome. It is made up of a N-terminal transmembrane helix, a cyanobactreria specific GAF domain, two PAS domains and a C-terminal histidine kinase.

To be fully functional CcaS has to bind the chromophore Phycocyanobilin (PCB) with its GAF-domain.

The GAF domain in this system has the ligation motif Cys-Leu, instead of the usual plant GAF-domain with Cys-His.

Green light system |

Its response regulator is CcaR (2), it belongs to the family of OmpR regulators. CcaR consists of an N-terminal receiver domain that can be phosphorylated by CcaS and a C-terminal DNA-binding domain that binds directly to the promoter region of cpcG2 (3). CpcG2 is an atypical phycobilisome which is playing a role in the energy transfer to photosystem I.

After light of a wavelength of 532 nm is sensed by the CcaS receptor, it changes its conformation. It undergoes autophosphorylation and the phosphate is transfered to the response regulator CcaR. Once phosphorylated, CcaR can bind to the specific promoter region of cpcG and activate gene expression.

As the green light sensing system was proven by J. J. Tabor to work also in E. coli, our plan is to integrate the genes for CcaS and CcaR into E. coli genome with a BAC (bacterial artificial chromosome). The researchers gene of interest just needs to be inserted behind the cpcG2 promoter region and transferred into "our" E .coli strain to become green light inducible.

References:

Yuu Hirose et al ( 2008 )"Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS is the green light receptor that induces the expression of phycobilisome linker protein." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105: 9528–9533.

Tabor, J. J., Levskaya, A., & Voigt, C. A. (2011). Multichromatic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Journal of Molecular Biology, 405(2), 315-324. Elsevier Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21035461

[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SEz70ClCetM| Blue light] receptor

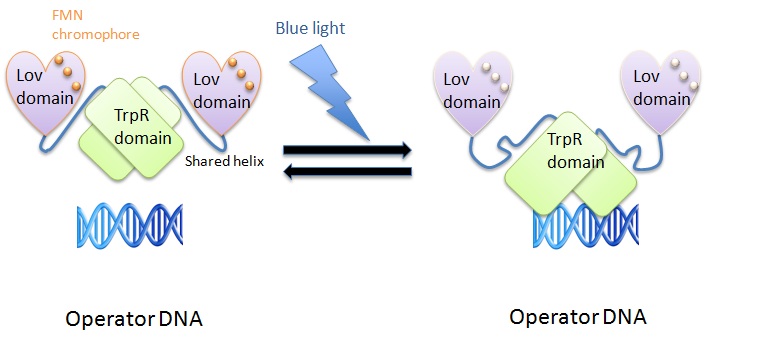

LOV- and tryptophan-activated protein (LovTAP)

We used the LovTAP protein designed by Strickland et al. to induce protein expression using blue light (470 nm). The LovTAP consists of the photoactive LOV2 domain of Avena sativa phototropin1 and the TrpR domain of E. coli as an output module. LOV2 is ligated via its carboxyl-terminal to the amino-terminal of TrpR with an α-helical domain linker. This shared helix couples the two functions of these proteins. The photoactive LOV domain (light, oxygen, voltage) absorbs photons leading to a formation of a covalent adduct between flavin mononucleotide (FMN) cofactor and a conserved cysteine residue (Strickland et al., 2008). The TrpR domain inhibits DNA digestion by nuclease.

blue light system |

The shared helix acts as a rigid lever arm and assoociates with the domains dependent of the light/dark state. This causes a steric overlap. Photoexcitation changes the conformational ensemble of the proteins and also changes the stability of the helix-domain contacts. This change shifts the relative affinity of the shared helix for each of the two domains. Photoexcitation sensed by one domain allows allosterical propagation to the other domain (Strickland et al., 2008).

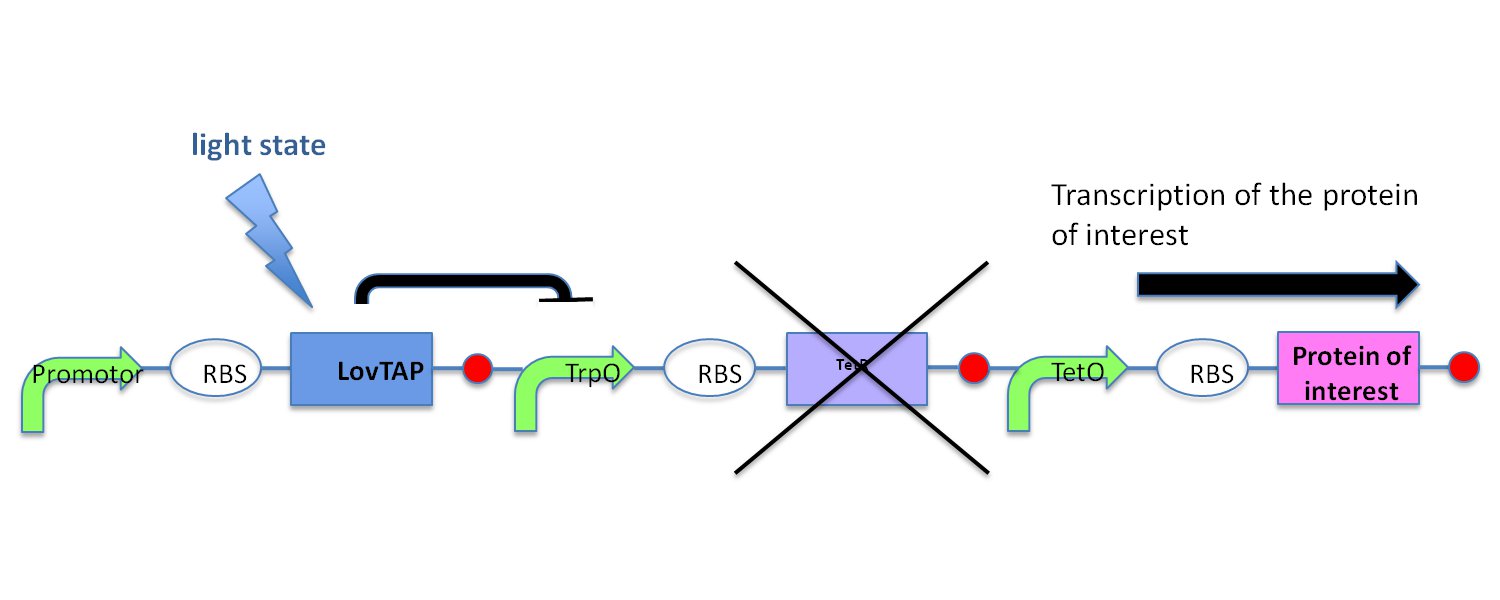

In the light state the LovTAP binds to the operator DNA and inhibits the gene expression. To avoid this inhibition, we cloned a Not-Gate after the LovTAP. Not-Gate is like an inverter, because it changes the input to its opposite. The Not-Gate consists of a tetracycline repressor and a TetR repressible promoter . In the light state the LovTAP binds to operator DNA and inhibits the expression of tetracycline repressor and the TetR promoter is active. In the dark state the tryptophan repressor is expressed and inhibits the expression of the protein of interest.

LovTAP with Not-Gate |

Problems arose during the cloning of the LovTAP and Not-Gate in pSB1C3 vector. A reason might be that the mutation of the SpeI restriction site to NehI in the suffix wasn´t succesful and therefore the digestion with NehI did not work. Somehow we could only clone the Not-Gate successful in the vector without the LovTAP.

References:

Strickland et al. 2008

“Light-activated DNA binding in a designed allosteric protein”

National Academy of Sciences (2008) 10709-10714

Red light receptor

The red light sensing system was used by various iGEM teams in the past,

that’s why we thought it shouldn’t be too difficult to integrate it into our project.

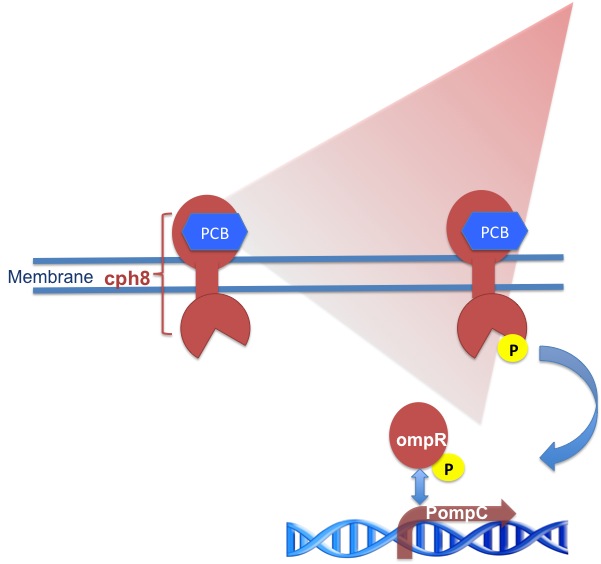

the red light receptor system |

It consists of a transmembrane part called cph8 , its response regulator OmpR and a co-responding promoter region PompC. Like the green light receptor it needs a chromophore like Phycocyanobilin (PCB) to be fully functional.

This is how it should work in theory:

The cph8 is a fusion protein of the phytochrome cph1 from Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 and the E. coli histidine kinase EnvZ. When cph8 is phosphorylated it passes a phosphoryl group to OmpR which binds to and activates transcription from PompC . (x) . OmpR is the response regulator for osmoregulation and as it is part of an important regulatory pathway in E. coli, you have to use an E. coli-strain deficient of EnvZ to make your system light dependent.

To establish this genes you need a part design like the one of [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_M30109 BBa_M30109] , but like other iGEM teams we had difficulties with this part and decided to assemble it ourselves.

References:

Tabor, J. J., Levskaya, A., & Voigt, C. A. (2011). Multichromatic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Journal of Molecular Biology, 405(2), 315-324. Elsevier Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21035461

Lysis cassette

The Concept

The idea behind our lysis cassette was to be able to achieve cell lysis by simply heating the bacteria to 42°C for a short period of time. This was accomplished by combining the biobricks [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K098995 BBa_K098995] (temperature sensitive promoter) and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K124017 BBa_K124017] (Bacteriophage λ lysis genes). Sequencing of these parts (carried out by GATC Biotech GmbH) showed some fundamental inconsistencies leading to a lot of time spent on fixing them.

The sequences were corrected and the new biobricks [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K608351 BBa_K608351] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K608352 BBa_K608352] were sent to the registry, although the novel temperature sensitive lysis cassette composite's sequence was verified some 18 hours before the Wiki-freeze, so that it could not be sent to the registry on time.

Nevertheless some preliminary OD-measurement results did hint at the expected functionality of the newly developed composite part.

Part Design

The temperature sensitive promoter ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K608351 BBa_K608351])

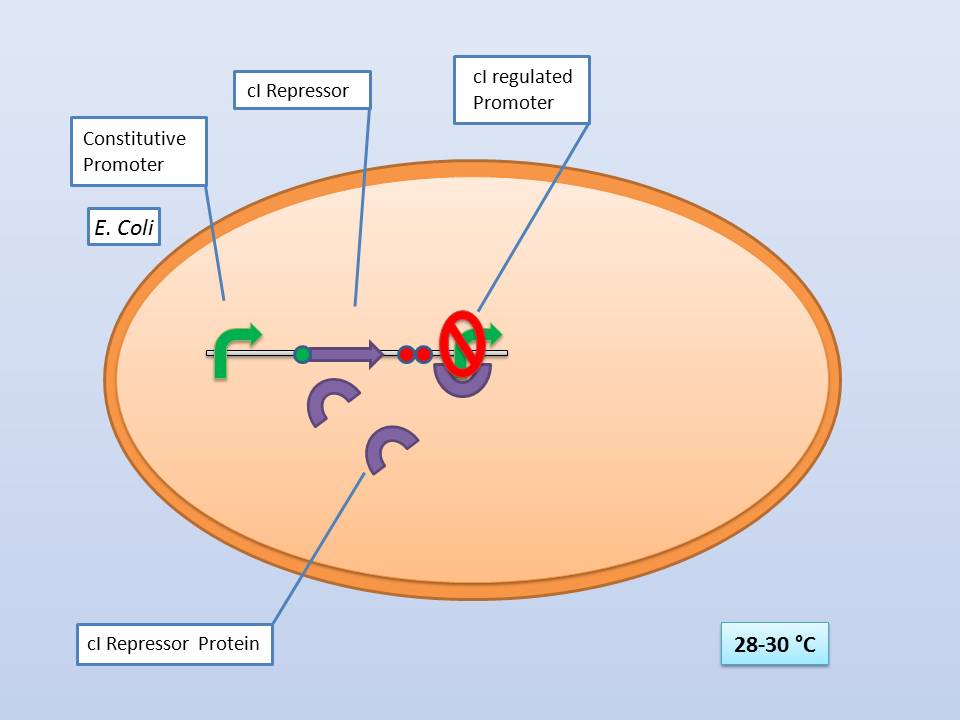

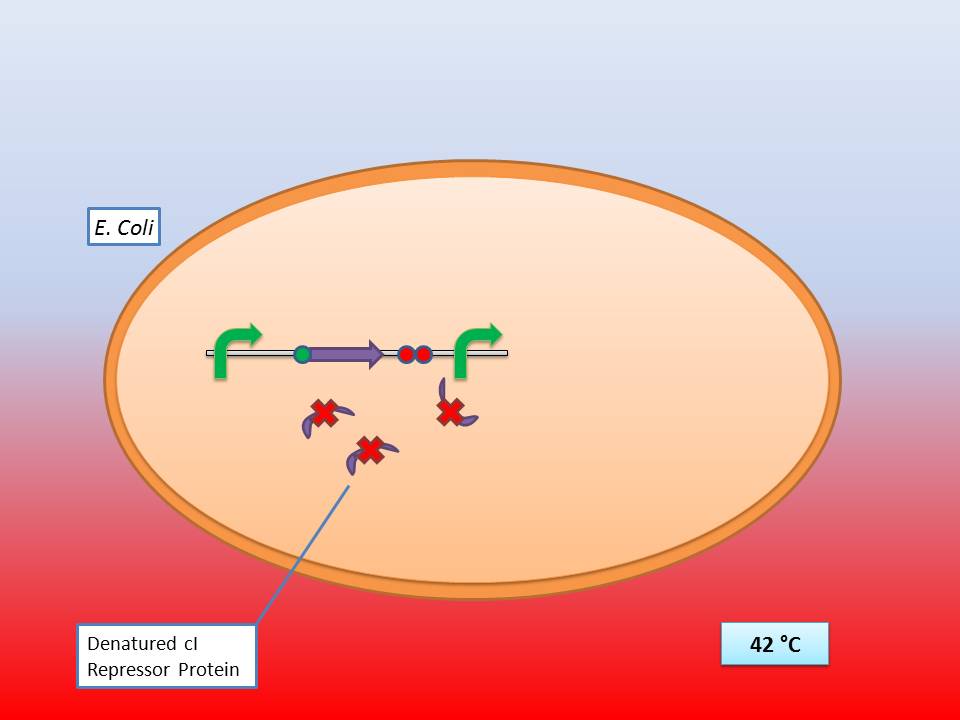

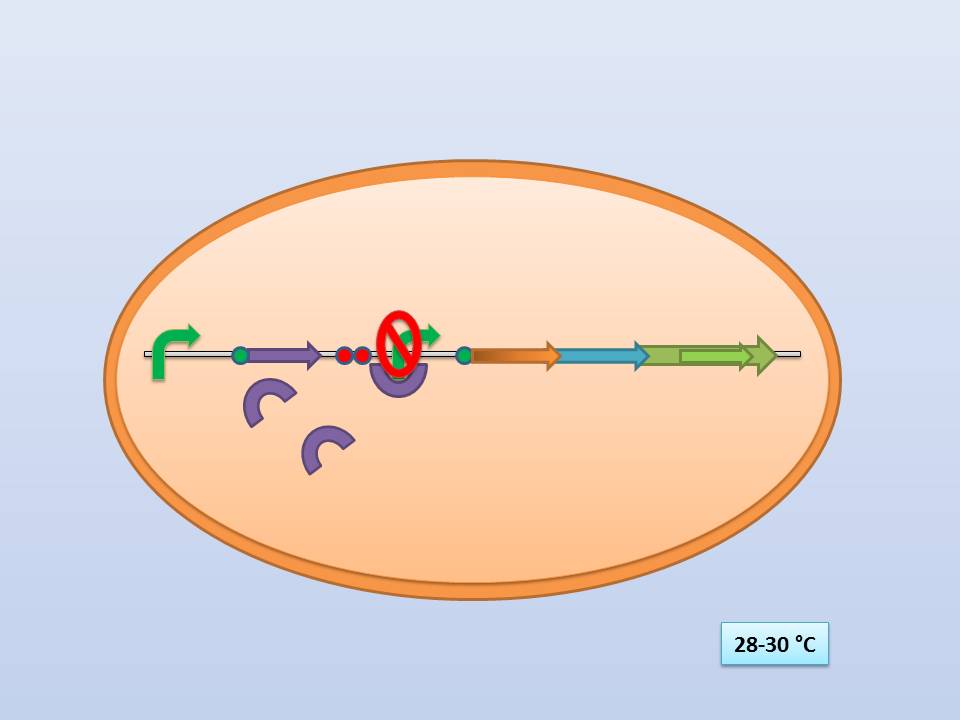

It consists of a constitutive promoter ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J23114 BBa_J23114]), the temperature sensitive λ cI repressor protein which has a cI857 mutation that results in denaturation of the repressor when the temperature is raised from 30°C to 42°C, and a cI regulated promoter based on the λ pR promoter ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0051 BBa_R0051]).

- Troubleshooting: http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K098995:Experience

|

The temperature sensitive promoter functioning at 28-30°C |

|

|

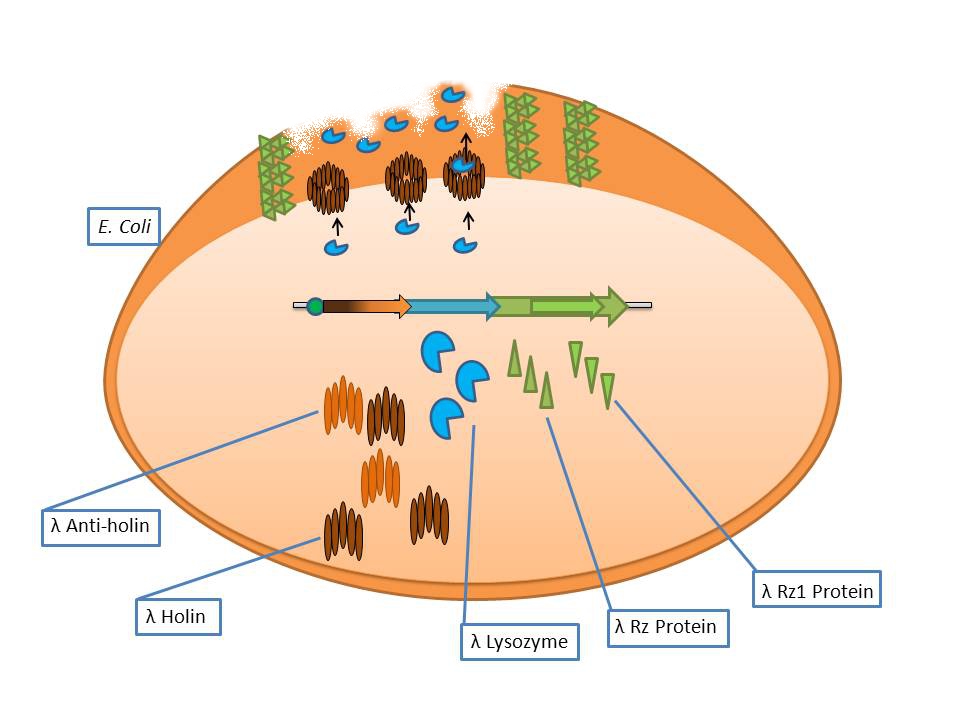

The λ lysis genes ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K608352 BBa_K608352])

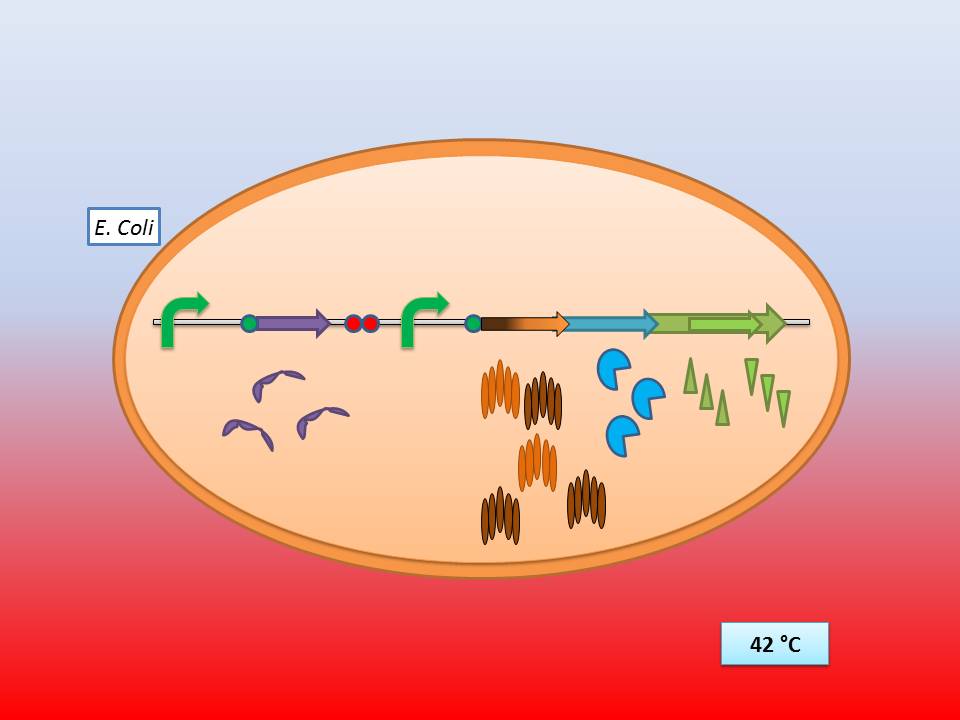

It consists of the standard bacteriophage λ lysis genes, ie S/S’, R, Rz/Rz1, coded in overlapping sequences with phase 1 and 2 frameshifts.

Bacteriophage λ lysis genes at work |

- S: λ Anti-Holin

- S’: λ Holin

- R: λ Endolysin

- Rz: Putative type-II signal anchor protein

- Rz1: Outer membrane lipoprotein

The phage λ lysozyme (R Endolysin) hydrolyses the beta-1,4-glycosidic bond between N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), but in order to degrade the cell wall it requires a small transmembrane protein called holin which perforates the membrane for endolysin to gain access to the murein [Ry Young et al].

The auxiliary lysis proteins Rz and Rz1 have long been known to play a vital role but have yet to be assigned a specific function stemming from functional and structural analysis. The assumption is that they form a complex spanning the periplasm and fuse the outer and inner membranes, removing the last physical barrier for cell lysis [Joel Berry et al].

- Troubleshooting: The biobrick did not have a RBS upstream of the CDS, so we had to clone the RBS [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0034 BBa_B0034] in order to make a translational unit for cloning with the temperature sensitive promoter

The temperature sensitive lysis cassette

The much anticipated part that we frustratingly could not clone in time to send to the registry.

Theoretically 28°C - 30°C incubation should repress the lysis genes, while a shift to 42°C would lead to their expression and finally cell lysis.

|

The temperature sensitive lysis cassette at 28-30°C |

|

References:

Nils B. Adey et al. 1995

“Characterization of phage that bind plastic from phage-displayed random peptide libraries”

Gene 156 (1995) 27-31

Alfredo Menendez & Jamie K. Scott 2005

“The nature of target-unrelated peptides recovered in the screening of phage-displayed random peptide libraries with antibodies”

Anal. Biochem. 336 (2005) 145-157

L. A. Cantarero et al. 1980

“The absorptive characteristics of proteins for polystyrene and their significance in solid phase immunoassays”

Anal. Biochem. 105 (1980) 375-382

Ry Young et al

“Phages will out: strategies of host cell lysis”

Trends in Microbiology Vol 8, Issue 3 (2000) 120-128

Joel Berry et al

“The final step in the phage infection cycle: the Rz and Rz1 lysis proteins link the inner and outer membranes”

Molecular Microbiology 70 (2008) 341–351

Bacterial artificial chromosome

Bacterial artificial chromosome a vector based on the single copy plasmid F-factor from Escherichia coli, which can host inserts from bacteria or other sources between 150 and 350 kilo base pairs (kbp) but up to 700 kbp, and hold them for more then 100 generations. The BAC vector has some common gene components that are: the oriS and repE which are responsible for the not bidirectional replication. The parA and parB genes control the copy number of the BAC. In addition there is a selection marker commonly an antibiotic resistance and finally the cloning segment with the restriction sites. This cloning segment will be flanked by a T7 and SP6 promoter. Usually BACs are used to build up libraries or genetically screening, through its stability.

We want to put most of our parts in a BAC so you can use it as our “Lab in a cell” system.

If you see all the different parts in our constructed system you recognize that it is impossible to put them all in one plasmid. But most of our parts if not all of them, are needed in every cell which should produce the proteins of interest. So this would be on the one hand a complicated way because you need more then three different plasmids and antibiotic resistance which is difficult and not stable, on the other hand it is an extremely time-consuming task to clone these whole things together.

To have a BAC which contains our precipitator, the lysis cassette and the most parts of our light inducible systems should not to be underestimated. It would be an easy, timesaving and stable construct.

References:

O'Connor M, Peifer M, Bender W (1989). "Construction of large DNA segments in Escherichia coli". Science 244 (4910): 1307–1312.

Shizuya H, Birren B, Kim U-J, Mancino V, Slepak T, Tachiiri Y, Simon M (1992). "Cloning and stable maintenance of 300-kilobase-pair fragments of human DNA in Escherichia coli using an F-factor-based vector". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89 (18): 8794–8797.

"

"

Contact

Contact