Team:UC Davis/PartFamilies

From 2011.igem.org

(Difference between revisions)

Aheuckroth (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (31 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

<h1>Make Your Own Part Families</h1> | <h1>Make Your Own Part Families</h1> | ||

<div class="floatbox3"> | <div class="floatbox3"> | ||

| - | Part families are a great asset to the Parts Registry. Our process for expanding basic parts into part families is quick, easy, and prioritizes the use of materials that most iGEM teams already have on hand. By following these steps, you can improve the utility of your favorite part and | + | Part families are a great asset to the Parts Registry. Our process for expanding basic parts into part families is quick, easy, and prioritizes the use of materials that most iGEM teams already have on hand. By following these steps, you can improve the utility of your favorite part and contribute to a strong foundation of useful parts for synthetic biologists around the world. |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="floatbox2"> | <div class="floatbox2"> | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Our part family expansion process is broken down into four major steps:<br><br> | Our part family expansion process is broken down into four major steps:<br><br> | ||

| - | <b>Selection</b>: Choose your basic part of interest and obtain a DNA sample.<br> | + | <b>Part Selection</b>: Choose your basic part of interest and obtain a DNA sample.<br> |

<b>Mutagenesis</b>: Create a library of mutants from your basic part.<br> | <b>Mutagenesis</b>: Create a library of mutants from your basic part.<br> | ||

<b>Screening</b>: Select a range of mutants that will offer the most utility for future projects.<br> | <b>Screening</b>: Select a range of mutants that will offer the most utility for future projects.<br> | ||

| - | <b>Characterization</b>: Collect detailed information on each mutant to document its behavior. | + | <b>Characterization</b>: Collect detailed information on each mutant to document its behavior.<br><br> |

| - | <br><br> | + | You can hear Nick and Aaron discuss our process on our <a href="http://www.soundcloud.com/igem-at-uc-davis/part-families-rock">Soundcloud</a> page. |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="floatbox2"> | <div class="floatbox2"> | ||

<h2>Selection</h2> | <h2>Selection</h2> | ||

| - | The <a href="http://partsregistry.org" target=_blank>Parts Registry</a> has a wide selection of basic parts that are good candidates for part family expansion. This includes promoters, repressors, reporter proteins, and many others. For our process to work properly, selected parts must contain standard VF2 and VR sites around the region of interest. <br><br> | + | The <a href="http://partsregistry.org" target=_blank>Parts Registry</a> has a wide selection of basic parts that are good candidates for part family expansion. This includes promoters, repressors, reporter proteins, and many others. For our process to work properly, selected parts must contain standard VF2 and VR sites around the region of interest. |

| + | <img src="http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6220/6283226081_f44225c7b6.jpg" width="300" height="200" align="right"> <br><br> | ||

Ideal parts are around 200 base pairs or more in length, as smaller parts show reduced levels of transformation success. Part selection is also key to the success of later screening and characterization steps: measuring the activity of parts often requires the use of a fluorescent reporter like GFP, so your parts must affect the expression of this reporter in some way. For example, promoter mutants can be used to transcribe different levels of reporter mRNA, and differences in the activity of reporter mutants can be measured directly.<br><br> | Ideal parts are around 200 base pairs or more in length, as smaller parts show reduced levels of transformation success. Part selection is also key to the success of later screening and characterization steps: measuring the activity of parts often requires the use of a fluorescent reporter like GFP, so your parts must affect the expression of this reporter in some way. For example, promoter mutants can be used to transcribe different levels of reporter mRNA, and differences in the activity of reporter mutants can be measured directly.<br><br> | ||

| - | We also recommend that parts be selected with their future utility in mind -- we chose to work with repressible promoters because they are frequently used in designing genetic circuits. This will help frame the paramater space over which mutants will be selected for final characterization, and helps judge the | + | We also recommend that parts be selected with their future utility in mind -- we chose to work with repressible promoters because they are frequently used in designing genetic circuits. This will help frame the paramater space over which mutants will be selected for final characterization, and helps judge the degree of mutagenesis required to achieve good mutant library resolution. |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="floatbox2"> | <div class="floatbox2"> | ||

| - | <h2> | + | <h2>Mutagenesis</h2> |

| - | Mutagenesis creates the genetic variation that leads to changes in part behavior. This can be achieved in a number of ways, but we | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/c/c5/Ucd_Pcrmutdiag.png" height="365" align="right"> |

| + | Mutagenesis creates the genetic variation that leads to changes in part behavior. This can be achieved in a number of ways, but we designed this process with the use of our suped-up <a href=https://2011.igem.org/Team:UC_Davis/Protocols#ER-PCR>error-prone PCR protocol</a> in mind. This protocol has been optimized specifically for creating mutants of Registry parts: it uses standard VF2 and VR primers, produces a large number of mutations per reaction for rapid library generation and visual screening, and it uses materials that are already present in most iGEM team labs. <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since the degree of mutation required to produce desirable levels of phenotype variation is not generally known before this step has been completed, we suggest performing several rounds of mutagenic PCR in succession, saving the products from each reaction, then digesting, ligating and transforming the results separately. This will produce plates of mutant transformants at different degrees of mutation from wild-type. <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We found that our protocol produces about 1 to 7 base pair mutations per kilobase each round of error-prone PCR, which was enough to visually identify GFP mutants (~800bp) on transformation plates after just one round and LacI promoter mutants (~200bp) after three rounds. We also observed a qualitative increase in successfully transformed colonies when we used a PCR purification kit on our PCR products before cutting them with restriction enzymes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="floatbox2"> | ||

| + | <h2>Screening</h2> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/e/e5/UCDScreeningdiagram.png" align="right" height="600"> | ||

| + | This is perhaps the most difficult step in the process of generating part families. All parts present a unique challenge: each part has a different set of characteristics that will be modified by mutagenesis over a theoretical range of useful values.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | First, a vector must be prepared into which the digested error-prone PCR products can be ligated for screening and characterization. This vector should associate reporter activity with the function of a mutant part. We have designed a generic screening plasmid, K611018, which can be used to assay promoters, repressors, and other regulatory sequences. It can be prepared for use with repressible promoters, for example, by ligating the wild-type repressor to the 3' end prior to digestion and ligation with promoter mutants.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting is a terrific tool for selecting individual bacteria based on reporter expression, but the cost of owning or renting a FACS machine can be prohibitive to many teams. As an alternative, we found that visually screening for GFP expression is an efficient way to initially screen mutant libraries. The increased mutation rate of our mutagenic PCR protocol is high enough that a range of colonies, from nearly-white to bright green, can generally be seen on successful transformation plates. The use of a hand-held long-wave UV lamp may assist in this process. While colonies across a wide range of GFP expression can be selected, not all variations in part behavior will be visible based on GFP fluorescence under these conditions. For this reason, many more colonies should be selected than will be expected to become part family members.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Further rounds of screening must be performed to narrow the choice of mutants down further. We used a Tecan InfiniTe M200 plate reader to measure the fluorescence activity of 250 uL liquid cultures of cells containing our promoter mutants. Fluorescence plate readers are an excellent tool for quantifying the activity of wild-type and mutant parts, but they are also expensive to purchase and take at least 12 hours to produce data on a set of cultures. Initial visual screening helps to reduce the total amount of plate reader access time required to select final mutants, and our team is currently exploring alternative options for the screening and characterization of cell cultures.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | While intermediate screening can be performed on single samples of cell culture, mutants should be run in triplicate at least once to ensure that their deviation from wild-type activity is repeatable. All plate reader runs should contain a wild-type control containing the part from which the mutants were generated ligated into the same screening vector, an optical density negative control containing only growth media and no cells, and a cell fluoresence control containing cell culture without reporter expression. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="floatbox2"> | ||

| + | <h2>Characterization</h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/f/f5/UCD_Characterizationdiagram.png" height="450" align="right"> | ||

| + | This step is important to ensuring that members of your part family will be usable by other synthetic biologists. Once you have selected your final set of mutants, miniprep them and send the DNA to be sequenced. Sequence data is essential for submission of parts to the Registry, and it can be used to associate changes in part functionality to mutations in DNA. <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The characterization process is much like screening, but performed in greater detail and with a limited number of samples. We used the same plate reader to perform our characterization, but instead of running many mutants on the same plate, we selected only a few and ran them under multiple conditions. These conditions will vary depending on the nature of the basic part you started with. Our regulatory mutant screening plasmid allows modulation of repressor or activator concentration by arabinose induction, and our LacI mutants were tested in response to IPTG, which binds the LacI repressor protein.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | When selecting reaction conditions to test, we suggest starting with the minimum and maximum values present in literature. For example, IPTG concentrations in liquid culture are generally around 1 mM, so we initially tried to characterize our LacI mutants at 0, .25, .5 and 1 mM. With this initial data, we realized we were far below the maximum induction strength for IPTG, and increased our maximum concentration to 5 mM instead. If possible, test the wild-type part against as many reaction conditions as possible to identify which ones produce the largest changes in activity, and then narrow down the number of samples to only those conditions.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Characterization data can be processed using tools like <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:UC_Davis/Attributions#Octave">Octave</a>. This data can be presented either in graphical images, or for web-based media, in a widget like the one found on our <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:UC_Davis/Data_LacI">LacI Data Page</a>. If you collect data that would benefit from being displayed in 3D, we encourage you to use our 3D Javascript plotting library, <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:UC_Davis/KO3D">KO3D</a>.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Submit your characterized part family members to the <a href="http://partsregistry.org" target=_blank>Parts Registry</a> in sequential order whenever possible. Include all characterization data and reference the basic part from which the family was derived. Provide information on your mutant library on the original part's experience page. We are currently pursuing ways advertising the presence of part families on the Registry. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | .. | ||

Latest revision as of 23:56, 28 October 2011

Start a Family

Got a favorite BioBrick? Check our our process for expanding basic parts into part families.Criteria

View our judging criteria for iGEM 2011 here.

Make Your Own Part Families

Part families are a great asset to the Parts Registry. Our process for expanding basic parts into part families is quick, easy, and prioritizes the use of materials that most iGEM teams already have on hand. By following these steps, you can improve the utility of your favorite part and contribute to a strong foundation of useful parts for synthetic biologists around the world.

Our Method

Our part family expansion process is broken down into four major steps:Part Selection: Choose your basic part of interest and obtain a DNA sample.

Mutagenesis: Create a library of mutants from your basic part.

Screening: Select a range of mutants that will offer the most utility for future projects.

Characterization: Collect detailed information on each mutant to document its behavior.

You can hear Nick and Aaron discuss our process on our Soundcloud page.

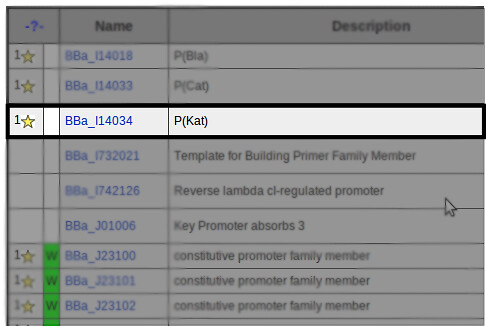

Selection

The Parts Registry has a wide selection of basic parts that are good candidates for part family expansion. This includes promoters, repressors, reporter proteins, and many others. For our process to work properly, selected parts must contain standard VF2 and VR sites around the region of interest.

Ideal parts are around 200 base pairs or more in length, as smaller parts show reduced levels of transformation success. Part selection is also key to the success of later screening and characterization steps: measuring the activity of parts often requires the use of a fluorescent reporter like GFP, so your parts must affect the expression of this reporter in some way. For example, promoter mutants can be used to transcribe different levels of reporter mRNA, and differences in the activity of reporter mutants can be measured directly.

We also recommend that parts be selected with their future utility in mind -- we chose to work with repressible promoters because they are frequently used in designing genetic circuits. This will help frame the paramater space over which mutants will be selected for final characterization, and helps judge the degree of mutagenesis required to achieve good mutant library resolution.

Mutagenesis

Mutagenesis creates the genetic variation that leads to changes in part behavior. This can be achieved in a number of ways, but we designed this process with the use of our suped-up error-prone PCR protocol in mind. This protocol has been optimized specifically for creating mutants of Registry parts: it uses standard VF2 and VR primers, produces a large number of mutations per reaction for rapid library generation and visual screening, and it uses materials that are already present in most iGEM team labs.

Mutagenesis creates the genetic variation that leads to changes in part behavior. This can be achieved in a number of ways, but we designed this process with the use of our suped-up error-prone PCR protocol in mind. This protocol has been optimized specifically for creating mutants of Registry parts: it uses standard VF2 and VR primers, produces a large number of mutations per reaction for rapid library generation and visual screening, and it uses materials that are already present in most iGEM team labs. Since the degree of mutation required to produce desirable levels of phenotype variation is not generally known before this step has been completed, we suggest performing several rounds of mutagenic PCR in succession, saving the products from each reaction, then digesting, ligating and transforming the results separately. This will produce plates of mutant transformants at different degrees of mutation from wild-type.

We found that our protocol produces about 1 to 7 base pair mutations per kilobase each round of error-prone PCR, which was enough to visually identify GFP mutants (~800bp) on transformation plates after just one round and LacI promoter mutants (~200bp) after three rounds. We also observed a qualitative increase in successfully transformed colonies when we used a PCR purification kit on our PCR products before cutting them with restriction enzymes.

Screening

This is perhaps the most difficult step in the process of generating part families. All parts present a unique challenge: each part has a different set of characteristics that will be modified by mutagenesis over a theoretical range of useful values.

This is perhaps the most difficult step in the process of generating part families. All parts present a unique challenge: each part has a different set of characteristics that will be modified by mutagenesis over a theoretical range of useful values.First, a vector must be prepared into which the digested error-prone PCR products can be ligated for screening and characterization. This vector should associate reporter activity with the function of a mutant part. We have designed a generic screening plasmid, K611018, which can be used to assay promoters, repressors, and other regulatory sequences. It can be prepared for use with repressible promoters, for example, by ligating the wild-type repressor to the 3' end prior to digestion and ligation with promoter mutants.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting is a terrific tool for selecting individual bacteria based on reporter expression, but the cost of owning or renting a FACS machine can be prohibitive to many teams. As an alternative, we found that visually screening for GFP expression is an efficient way to initially screen mutant libraries. The increased mutation rate of our mutagenic PCR protocol is high enough that a range of colonies, from nearly-white to bright green, can generally be seen on successful transformation plates. The use of a hand-held long-wave UV lamp may assist in this process. While colonies across a wide range of GFP expression can be selected, not all variations in part behavior will be visible based on GFP fluorescence under these conditions. For this reason, many more colonies should be selected than will be expected to become part family members.

Further rounds of screening must be performed to narrow the choice of mutants down further. We used a Tecan InfiniTe M200 plate reader to measure the fluorescence activity of 250 uL liquid cultures of cells containing our promoter mutants. Fluorescence plate readers are an excellent tool for quantifying the activity of wild-type and mutant parts, but they are also expensive to purchase and take at least 12 hours to produce data on a set of cultures. Initial visual screening helps to reduce the total amount of plate reader access time required to select final mutants, and our team is currently exploring alternative options for the screening and characterization of cell cultures.

While intermediate screening can be performed on single samples of cell culture, mutants should be run in triplicate at least once to ensure that their deviation from wild-type activity is repeatable. All plate reader runs should contain a wild-type control containing the part from which the mutants were generated ligated into the same screening vector, an optical density negative control containing only growth media and no cells, and a cell fluoresence control containing cell culture without reporter expression.

Characterization

This step is important to ensuring that members of your part family will be usable by other synthetic biologists. Once you have selected your final set of mutants, miniprep them and send the DNA to be sequenced. Sequence data is essential for submission of parts to the Registry, and it can be used to associate changes in part functionality to mutations in DNA.

This step is important to ensuring that members of your part family will be usable by other synthetic biologists. Once you have selected your final set of mutants, miniprep them and send the DNA to be sequenced. Sequence data is essential for submission of parts to the Registry, and it can be used to associate changes in part functionality to mutations in DNA. The characterization process is much like screening, but performed in greater detail and with a limited number of samples. We used the same plate reader to perform our characterization, but instead of running many mutants on the same plate, we selected only a few and ran them under multiple conditions. These conditions will vary depending on the nature of the basic part you started with. Our regulatory mutant screening plasmid allows modulation of repressor or activator concentration by arabinose induction, and our LacI mutants were tested in response to IPTG, which binds the LacI repressor protein.

When selecting reaction conditions to test, we suggest starting with the minimum and maximum values present in literature. For example, IPTG concentrations in liquid culture are generally around 1 mM, so we initially tried to characterize our LacI mutants at 0, .25, .5 and 1 mM. With this initial data, we realized we were far below the maximum induction strength for IPTG, and increased our maximum concentration to 5 mM instead. If possible, test the wild-type part against as many reaction conditions as possible to identify which ones produce the largest changes in activity, and then narrow down the number of samples to only those conditions.

Characterization data can be processed using tools like Octave. This data can be presented either in graphical images, or for web-based media, in a widget like the one found on our LacI Data Page. If you collect data that would benefit from being displayed in 3D, we encourage you to use our 3D Javascript plotting library, KO3D.

Submit your characterized part family members to the Parts Registry in sequential order whenever possible. Include all characterization data and reference the basic part from which the family was derived. Provide information on your mutant library on the original part's experience page. We are currently pursuing ways advertising the presence of part families on the Registry.

"

"