Team:NYMU-Taipei/optomagnetic-design

From 2011.igem.org

(→The BRET Phenomenon) |

|||

| (141 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | {{:Team:NYMU-Taipei | + | {{:Team:NYMU-Taipei/Templates/Header/menubar}} |

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''Optomagnetic Design'''</font>== | |

| + | <font size=3>In brief, the optomagnetic design bases heavily on a hypothesis that magnetic force may generate conformational alteration on magnetite tight-binding protein, mms13, which finally gives way to BRET / BiFC-base BRET between yellow fluorescence protein (YFP) and Renilla luciferase (rLuc). According to the design, which, in some aspects more likely serves the aim of our project, we have searched desperately for ways to solve numerous obstacles we may encounter. See what we've struggled through the expedition.</font> | ||

| - | + | '''<font size=5><font color=gray>Follow up!</font></font>''' | |

| - | + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''Magnetotactic Bacteria'''</font>== | |

| + | <font size=3>The reason for choosing magnetotactic bacteria lies in its special magnetic field-sensing capabilities. Since the only way to achieving a wireless system is through electromagnetic oscillation, choosing this bacterial strain in shouldering the mission may reasonably suffice an educated attempt.</font> | ||

| - | + | <font size=3>Among the four types of non-contact forces, strong nuclear force and weak nuclear force seem unrelated to biological phenomena, while gravitation shows a great connection yet still incompetent for establishing a system subject to high-frequency stimulation. Among the remaining electromagnetic forces, the establishment of an electric force field requires bare charge, thus only magnetic force field remains and seemed reasonably related to biological systems through the existence of the magnetotactic bacterial species.</font> | |

| + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''Choosing The Anchor Protein mms13'''</font>== | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>Once we have chosen magnetism as our only gateway to wireless probing of biological systems, the problem shifts deeper into the detailed molecular mechanisms situated on '''the very interface''' of magnetic force field and biochemical reactions.</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>We soon realized that the linkage between high-frequency biological responses and electromagnetic oscillation could happen if and only if the ''responses'' are directly driven by the oscillation of magnetic forces, that is, through the vibration of bacterial magnetites. In this sense, though bold for sure, we turned to magnetite tight-binding magnetosome proteins.</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>[[Image:magnetite tight-binding protein SDS-PAGE.gif|thumb|400px|'''Fig a:''' magnetite tight-binding protein on 2-D SDS-PAGE [http://www.jbc.org/content/278/10/8745.abstract Matsunaga T.'', et al.'']]]</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>In the article titled "[http://www.jbc.org/content/278/10/8745.abstract A Novel Protein Tightly Bound to Bacterial Magnetic Particles in ''Magnetospirillum magneticum'' Strain AMB-1]" published by Matsunaga T.'', et al.'' in 2003, the author identified four magnetite tight-binding proteins. Among the four, mms6 has one predicted transmembrane domains and attaches to the magnetite using its N-terminal; mms5 and mms7 are predicted as a peripheral protein or membrane protein with uncertain number of transmembrane domains on the magnetosome membrane and a single transmembrane protein, respectively. Those three show sequence homologies in N-terminal peptides as well as putative transmembrane domains (See Fig. a), thus are predictive of a cluster of N-terminal binding transmembrane protein against bacterial magnetite.</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>[[Image:magnetite tight-binding protein homology.gif|thumb|400px|'''Fig b:''' magnetite tight-binding protein hydrophobic region homologies [http://www.jbc.org/content/278/10/8745.abstract Matsunaga T.'', et al.'']]]</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>Mms13, on the other hand, is of very unique properties. Firstly, it shows no significant homology in hydrophobic regions with mms5, mms5 and, mms7. Secondly, predictive as well as experimental evidence showed signs on its magnetite tight-binding sequences situated on the extracellular loop between the two transmembrane helices. Also, according to subsequent detailed predictive efforts facilitated by numerous bioinformatic tools, this protein shows high consistency in its orientation and organization on secondary structure.</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''Wavelength for Optogenetic Neurostimulation'''</font>== | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>[[Image:channelrhodopsins and YFP.gif|thumb|400px|'''Fig b:''' [http://www.google.com.tw/url?sa=t&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CDYQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.cell.com%2Fneuron%2Fabstract%2FS0896-6273(11)00504-6&ei=ROaMTs2uCuPYmAX5puyPBA&usg=AFQjCNHAd7LbfjrJPi8g0m0vcv6qqzmqpg Karl Deissorth'', et al.'']]]</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>According to an [http://www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273(11)00504-6 outstanding compilation] by Karl Deisseroth'', et al.'' on current channelrhodopsins used in various stimulatory experiments. The emission wavelength of YFP magically spanned through all sorts of channelrhodopsins spanning various time scales from fast inhibition, fast excitation to biochemical modulation. We were just as surprised as this may be for you. But from this we derived our usage of YFP as light donor, indicating that the next question lies in achieving light emission by YFP at ultra-high frequencies.</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | =='''<font size=5><font color=crimson>The BRET Phenomenon</font>'''== | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3> | ||

| + | How to use the conformation change of the Mms13 transmembrane protein to induce the light? <font color=MidnightBlue>We first came up with the idea by using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)</font>. BRET is based on resonance energy transfer between a light-emitting enzyme and a fluorescent acceptor (Johan Bacart, et al., 2008). For example, the energy derived from a luciferase reaction can be used to excite a fluorescent protein when the latter is in close proximity to the luciferase enzyme. Several other methods developed are shown in Table 1. | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3>[[Image: table1_NYMU.png|frame|Table 1: Several BRET methods have been developed.(Cite from: <u>http://www.berthold.com/ww/en/pub/bioanalytik/applikation/bret.cfm)</u>]]</font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3> | ||

| + | We chose the original BRET method using coelenterazine (luciferin) as substrate in BRET 1 method (See Figure 1). What we do is anchoring the YFP on the N-terminus of Mms13 and r-Luciferase on the C-terminus. <font color=mediumblueblue>We expect that when the magnetic force applied on the membrane and changed the conformation of Mms13 would lead to the close proximity between YFP and r-Luciferase and thus induce fluorescent phenomenon by BRET method)(See Figure 1).</font> | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=3> | ||

The advantage of BRET is that it is a non-radioactive and homogeneous technology. There is no auto-fluorescence coming from compounds or cell and buffer components as no light source is required. And the most of all, it make the conformation change of Mms13 possible to induce optomagnetic enlightment in bacteria. So, are we satisfied with our BRET design? The answer is no; the BRET method is good but not good enough in our project. | The advantage of BRET is that it is a non-radioactive and homogeneous technology. There is no auto-fluorescence coming from compounds or cell and buffer components as no light source is required. And the most of all, it make the conformation change of Mms13 possible to induce optomagnetic enlightment in bacteria. So, are we satisfied with our BRET design? The answer is no; the BRET method is good but not good enough in our project. | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| - | = | + | <font size=3> |

| + | [[Image: bifc-bret.png|frame|Fig. 2: The figure in the left is our initial design by using BRET phenomenon to generate light. As for the right one, we made a little change using BiFC-based BRET with the designed peptides to make the light wobbling and induce the on-and-off neural control system.]] | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| - | + | <font size=3> | |

| + | [[Image: bret_NYMU.png|frame|none|Fig. 1: Demonstration of our BRET design.]] | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| - | + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''The BiFC-based BRET Phenomenon'''</font>== | |

| - | + | <font size=3> | |

| + | <font color=mediumblue>It is known that transmembrane (TM) proteins usually have high propensities between the inter-helices</font>. Mms13 possesses two tightly-interacting transmembrane helices present as the major obstacle within our optomagnetic design, since theoretically, BRET will be an constitutive phenomena, leading to uninhibited excitation / unregulated inhibition of target neurons. However, the anticipated model we proposed rooted heavily in induced BRET with conformational wobbling within mms13, functioning as switches for neurons shifting back and forth between '''"ON"''' and '''"OFF"''' states. | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| - | + | <font size=3> | |

| + | We found inspiration from a paper associated with the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) method. The BiFC assay is based on the association between two nonfluorescent fragments of a fluorescent protein. When those fragments are brought in proximity to each other by an interaction between proteins, they would fuse into one functional fluorescent protein (Tom K. Kerppola., 2008). <font color=mediumblue>We came up with the idea by mixing the BiFC method and BRET phenomenon into the BiFC-based BRET design. (See Figure 2)</font> | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| - | = | + | <font size=3> |

| + | In our BiFC-based BRET design, we anchored a half of a YFP fragment (with YFP C-terminus) on the inter-helical inhibitor (the CHAMP peptide design). By using the inhibitor, we can affect the tight interaction between Mms13’s two helices, and the constant light induced form BRET phenomenon can also be blocked. The rest of the design is to get the other half of the YFP (with YFP N-terminus) anchored on the N-terminus of Mms13 and anchored the r-Luciferase on C-terminus of Mms13. The result is that when there is no magnetic force applied to Mms13, two helices of Mms13 will have further inter-helical distance due to the inhibitor (CHAMP design) and the BRET phenomenon will not perform due to the lack of close proximity between two helices. When we apply magnetic force to Mms13, the helices of the transmembrane protein will be pulled together and will induced the BRET phenomenon to emit fluorescence. | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| - | CHAMP | + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''The CHAMP Design'''</font>== |

| - | + | <font size=3> | |

| + | CHAMP, the computed helical anti-membrane protein, is designed by one of the computational and genetic methods available to engineer antibody-like molecules that target the water-soluble regions of tansmembrane (TM) proteins (Hang Yin, et al., 2007). | ||

| - | == | + | <font color=mediumblue>In the project, we want to use this designed peptide, CHAMP sequence, to inhibit the tight interaction between two helices of membrane protein Mms13 so that we can successfully use mechanical force to change the conformation of Mms13 to induce the BiFC-based BRET phenomenon.</font> The details of the CHAMP design is shown in [https://2011.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Team:NYMU-Taipei/modelling-protein-structure-champ-design protein modelling]. |

| + | </font> | ||

| + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''Our Constructs'''</font>== | ||

| + | <font size=3> | ||

We have six constructs for our design including both positive and negative controls. | We have six constructs for our design including both positive and negative controls. | ||

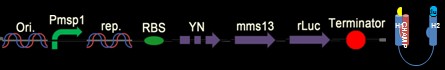

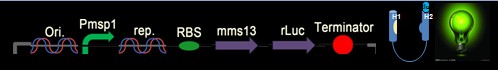

| - | [[Image: | + | [[Image: c1_NYMU.png|frame|none|Fig. 3: The main design construct. Ori is the origin of replication of AMB-1. Pmsp1 is the promoter for AMB-1.]] |

| - | + | [[Image: c2_NYMU.png|frame|none|Fig. 4: A construct without YC on the CHAMP is our negative control in our design. It would not light up no matter there is magnetic field applied or not.]] | |

| - | + | [[Image: c3_NYMU.png|frame|none|Fig. 5:. We design this construct with the whole YFP on the N-terminus of Mms13 and the CHAMP design to induce the BRET phenomenon. We suppose that with the CHMAP design, the construct will light up only when magnetic force is applied.]] | |

| - | [[Image: | + | [[Image: c4_NYMU.png|frame|none|Fig. 6: This design is constructed with the whole YFP on the N-terminus of Mms13 but “without” the CHAMP design. The construct should be a positive control with constant light no matter whether force is applied or not.]] |

| - | + | [[Image: c5_NYMU.png|frame|none|Fig. 7: The design construct is similar with construct in Fig. 5. Why we construct this design with the whole YFP on the C-terminus of the CHAMP design instead of Mms13’s N-terminus is that we try to avoid the interferences of DNA transformation with sequences added in front of the natural construct. The construct is supposed to light up when force pull the Mms13 and turn off if no magnetic field is applied.]] | |

| + | [[Image: c6_NYMU.png|frame|none|Fig. 8: In this last construct, only r-luciferase anchored on Mms13’s C-terminus. It will light up in yellow light (with 580 nm wavelength) due to the luciferase reaction, instead of the green light induced from BRET phenomenon (540 nm wavelength).]] | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''Modeling For Optomagnetic Design'''</font>== | ||

| + | <font size=3> | ||

| + | Though we have already done the design part of our project, we may be challenged by whether it can function in reality or not. We consulted with Professor Chun-Min Lo who has a professional background in biomechanics. One of his research interests is to apply magnetic force on the super magnetic particles contact on the cell membrane and measure the cell’s morphology and biomechanics to study the growth of cells. <font color=mediumblue>After we told him about our project and our final goal to achieve, he showed interest and was willing to help us in calculating and modeling our optomagnetic design and he also generously supplied electromagnets, a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by the flow of electric current, in his lab.</font> We then modeled and calculated the force and magnetic field applied to the magnetic bacteria by using Professor Chun-Min Lo’s devices. (CM Lo, et al., 1998) | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image: fdevice.png|frame|Fig. 4: Magnetic bead force application. A schematic of the experimental setup, with the electromagnet device shown in cross section. (Joseph N. Fass, et al., 2003) The difference between our project and the study is that there is no need to bind the magnetic particles on cell membrane, since AMB-1 has its own magnetic beads (magnetosomes) and AMB-1 can be simply put on the medium they used to live and grow without adding other chemicals.]] | ||

| + | </font> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''Activation-Required Magnetic Force'''</font>== | ||

| + | <font size=3> | ||

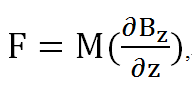

We calculated the force per unit volume of magnetosome by electronic balance, and also from the measured field of the permanent magnet. (Glogauer and Ferrier, 1998) The magnitude of the magnetic force per unit volume of iron oxide beads would be | We calculated the force per unit volume of magnetosome by electronic balance, and also from the measured field of the permanent magnet. (Glogauer and Ferrier, 1998) The magnitude of the magnetic force per unit volume of iron oxide beads would be | ||

| Line 52: | Line 110: | ||

Where M is the magnetization of the beads and δBz/δz is the gradient of the magnetic field along the normal line to the center of the pole face. | Where M is the magnetization of the beads and δBz/δz is the gradient of the magnetic field along the normal line to the center of the pole face. | ||

| - | The magnetosome crystal is known to have high chemical purity so its magnetization can reach to the saturation limit for 3*10 | + | The magnetosome crystal is known to have high chemical purity so its magnetization can reach to the saturation limit for 3*10<sup>5</sup> A/m. The average diameter of the magnetosome is 46 nm in magnetic bacteria, so the volume per bead will be 4.077*10<sup>-22</sup> m<sup>3</sup>. By calculating the data in the paper, we discovered that the cell can have very large scale of deformation when only around 2 nN is applied. With just 2 nN force, we can that track that cell and we can then trace back to the gradient of the magnetic field we should apply to the bacteria. |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | The average number of magnetosomes in magnetic bacteria is 20 particles. We should apply 2 nN/20=0.1 nN to one magnetosome. Dividing this by the total magnetosome volume (4.077*10<sup>-22</sup> m<sup>3</sup>), there would be 0.1 nN / (4.077*10<sup>-22</sup> m<sup>3</sup>)≈2.453*10<sup>11</sup> N/m<sup>3</sup> for force per volume. The gradient we need can be measured by dividing the force applied per volume to the saturated magnetization, which is: (2.453*10<sup>11</sup> N/m<sup>3</sup>)/(3*10<sup>5</sup> A/m)≈8.176*10<sup>5</sup> T/m. | |

| - | + | However, we certainly do not need the high gradient of up to 8.176*10<sup>5</sup> T/m. Because the need to pull the membrane and change the conformation of proteins would not require that much force. If the devices we apply now would not strong enough to change Mms13’s conformation, there is still nothing to worry about because we can add more turns per unit length of electromagnet to increase the magnetic gradient and thus induce stronger force to fulfill our goal. | |

[[Image: electromagnet.png|frame|Fig. 6: A magnetic trap for high-force cell probing is typically composed of an electromagnet with a sharp tip on a micromanipulator. (Hayden Huang, et al., 2004) If the force is not strong enough to change Mms13’s conformation we can add more turns per unit length of electromagnet to increase the magnetic gradient and thus induce stronger force to fulfill our goal.]] | [[Image: electromagnet.png|frame|Fig. 6: A magnetic trap for high-force cell probing is typically composed of an electromagnet with a sharp tip on a micromanipulator. (Hayden Huang, et al., 2004) If the force is not strong enough to change Mms13’s conformation we can add more turns per unit length of electromagnet to increase the magnetic gradient and thus induce stronger force to fulfill our goal.]] | ||

| - | [[Image: | + | [[Image: cell_NYMU.png|frame|none|Fig. 5: Neurite initiation and elongation in response to applied force of only 450 pN. (Joseph N. Fass, et al., 2003)]] |

| - | + | <center>[[Image: device.png|frame|none|Fig. 7: Measurements of magnetic devices-Electromagnet Gausses at Measured Distances by AZeer Enterprises, LLC]]</center> | |

| + | </font> | ||

| + | ==<font size=5><font color=crimson>'''References'''</font>== | ||

| + | <font size=3> | ||

* Johan Bacart, Caroline Corbel, Ralf Jockers, Stéphane Bach, Cyril Couturier Dr. (2008) The BRET technology and its application to screening assays. Biotechnology Journal Volume 3, Issue 3: 311–324 | * Johan Bacart, Caroline Corbel, Ralf Jockers, Stéphane Bach, Cyril Couturier Dr. (2008) The BRET technology and its application to screening assays. Biotechnology Journal Volume 3, Issue 3: 311–324 | ||

| Line 72: | Line 131: | ||

* Tom K. Kerppola. (2008) Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) Analysis as a Probe of Protein Interactions in Living Cells. Annu Rev Biophys 37: 465–487. | * Tom K. Kerppola. (2008) Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) Analysis as a Probe of Protein Interactions in Living Cells. Annu Rev Biophys 37: 465–487. | ||

| - | * Hang Yin, Joanna S. Slusky, Bryan W. Berger, Robin S. Walters, Gaston Vilaire, | + | * Hang Yin, Joanna S. Slusky, Bryan W. Berger, Robin S. Walters, Gaston Vilaire, Rustem I. Litvinov, James D. Lear, Gregory A. Caputo, Joel S. Bennett, William F. DeGrado (2007). Supporting Online Material for Computational Design of Peptides That Target Transmembrane Helices. Science 315, 1817. |

| - | Rustem I. Litvinov, James D. Lear, Gregory A. Caputo, Joel S. Bennett, William F. | + | |

| - | DeGrado (2007). Supporting Online Material for Computational Design of Peptides That Target Transmembrane Helices. Science 315, 1817. | + | |

* J. S. Slusky, H. Yin and W. F. DeGrado. (2009) Understanding Membrane Proteins. How to Design Inhibitors of Transmembrane Protein—Protein Interactions. PROTEIN ENGINEERING Nucleic Acids and Molecular Biology 22, 315-337. | * J. S. Slusky, H. Yin and W. F. DeGrado. (2009) Understanding Membrane Proteins. How to Design Inhibitors of Transmembrane Protein—Protein Interactions. PROTEIN ENGINEERING Nucleic Acids and Molecular Biology 22, 315-337. | ||

| Line 87: | Line 144: | ||

* Hayden Huang, Jeremy Sylvan, Maxine Jonas, Rita Barresi, Peter T. C. So, Kevin P. Campbell, and Richard T. Lee. (2005) Cell stiffness and receptors: evidence for cytoskeletal subnetworks. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C72–C80. | * Hayden Huang, Jeremy Sylvan, Maxine Jonas, Rita Barresi, Peter T. C. So, Kevin P. Campbell, and Richard T. Lee. (2005) Cell stiffness and receptors: evidence for cytoskeletal subnetworks. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C72–C80. | ||

| + | </font> | ||

Latest revision as of 22:35, 28 October 2011

Optomagnetic Design

In brief, the optomagnetic design bases heavily on a hypothesis that magnetic force may generate conformational alteration on magnetite tight-binding protein, mms13, which finally gives way to BRET / BiFC-base BRET between yellow fluorescence protein (YFP) and Renilla luciferase (rLuc). According to the design, which, in some aspects more likely serves the aim of our project, we have searched desperately for ways to solve numerous obstacles we may encounter. See what we've struggled through the expedition.

Follow up!

Magnetotactic Bacteria

The reason for choosing magnetotactic bacteria lies in its special magnetic field-sensing capabilities. Since the only way to achieving a wireless system is through electromagnetic oscillation, choosing this bacterial strain in shouldering the mission may reasonably suffice an educated attempt.

Among the four types of non-contact forces, strong nuclear force and weak nuclear force seem unrelated to biological phenomena, while gravitation shows a great connection yet still incompetent for establishing a system subject to high-frequency stimulation. Among the remaining electromagnetic forces, the establishment of an electric force field requires bare charge, thus only magnetic force field remains and seemed reasonably related to biological systems through the existence of the magnetotactic bacterial species.

Choosing The Anchor Protein mms13

Once we have chosen magnetism as our only gateway to wireless probing of biological systems, the problem shifts deeper into the detailed molecular mechanisms situated on the very interface of magnetic force field and biochemical reactions.

We soon realized that the linkage between high-frequency biological responses and electromagnetic oscillation could happen if and only if the responses are directly driven by the oscillation of magnetic forces, that is, through the vibration of bacterial magnetites. In this sense, though bold for sure, we turned to magnetite tight-binding magnetosome proteins.

In the article titled "[http://www.jbc.org/content/278/10/8745.abstract A Novel Protein Tightly Bound to Bacterial Magnetic Particles in Magnetospirillum magneticum Strain AMB-1]" published by Matsunaga T., et al. in 2003, the author identified four magnetite tight-binding proteins. Among the four, mms6 has one predicted transmembrane domains and attaches to the magnetite using its N-terminal; mms5 and mms7 are predicted as a peripheral protein or membrane protein with uncertain number of transmembrane domains on the magnetosome membrane and a single transmembrane protein, respectively. Those three show sequence homologies in N-terminal peptides as well as putative transmembrane domains (See Fig. a), thus are predictive of a cluster of N-terminal binding transmembrane protein against bacterial magnetite.

Mms13, on the other hand, is of very unique properties. Firstly, it shows no significant homology in hydrophobic regions with mms5, mms5 and, mms7. Secondly, predictive as well as experimental evidence showed signs on its magnetite tight-binding sequences situated on the extracellular loop between the two transmembrane helices. Also, according to subsequent detailed predictive efforts facilitated by numerous bioinformatic tools, this protein shows high consistency in its orientation and organization on secondary structure.

Wavelength for Optogenetic Neurostimulation

According to an [http://www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273(11)00504-6 outstanding compilation] by Karl Deisseroth, et al. on current channelrhodopsins used in various stimulatory experiments. The emission wavelength of YFP magically spanned through all sorts of channelrhodopsins spanning various time scales from fast inhibition, fast excitation to biochemical modulation. We were just as surprised as this may be for you. But from this we derived our usage of YFP as light donor, indicating that the next question lies in achieving light emission by YFP at ultra-high frequencies.

The BRET Phenomenon

How to use the conformation change of the Mms13 transmembrane protein to induce the light? We first came up with the idea by using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). BRET is based on resonance energy transfer between a light-emitting enzyme and a fluorescent acceptor (Johan Bacart, et al., 2008). For example, the energy derived from a luciferase reaction can be used to excite a fluorescent protein when the latter is in close proximity to the luciferase enzyme. Several other methods developed are shown in Table 1.

We chose the original BRET method using coelenterazine (luciferin) as substrate in BRET 1 method (See Figure 1). What we do is anchoring the YFP on the N-terminus of Mms13 and r-Luciferase on the C-terminus. We expect that when the magnetic force applied on the membrane and changed the conformation of Mms13 would lead to the close proximity between YFP and r-Luciferase and thus induce fluorescent phenomenon by BRET method)(See Figure 1).

The advantage of BRET is that it is a non-radioactive and homogeneous technology. There is no auto-fluorescence coming from compounds or cell and buffer components as no light source is required. And the most of all, it make the conformation change of Mms13 possible to induce optomagnetic enlightment in bacteria. So, are we satisfied with our BRET design? The answer is no; the BRET method is good but not good enough in our project.

The BiFC-based BRET Phenomenon

It is known that transmembrane (TM) proteins usually have high propensities between the inter-helices. Mms13 possesses two tightly-interacting transmembrane helices present as the major obstacle within our optomagnetic design, since theoretically, BRET will be an constitutive phenomena, leading to uninhibited excitation / unregulated inhibition of target neurons. However, the anticipated model we proposed rooted heavily in induced BRET with conformational wobbling within mms13, functioning as switches for neurons shifting back and forth between "ON" and "OFF" states.

We found inspiration from a paper associated with the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) method. The BiFC assay is based on the association between two nonfluorescent fragments of a fluorescent protein. When those fragments are brought in proximity to each other by an interaction between proteins, they would fuse into one functional fluorescent protein (Tom K. Kerppola., 2008). We came up with the idea by mixing the BiFC method and BRET phenomenon into the BiFC-based BRET design. (See Figure 2)

In our BiFC-based BRET design, we anchored a half of a YFP fragment (with YFP C-terminus) on the inter-helical inhibitor (the CHAMP peptide design). By using the inhibitor, we can affect the tight interaction between Mms13’s two helices, and the constant light induced form BRET phenomenon can also be blocked. The rest of the design is to get the other half of the YFP (with YFP N-terminus) anchored on the N-terminus of Mms13 and anchored the r-Luciferase on C-terminus of Mms13. The result is that when there is no magnetic force applied to Mms13, two helices of Mms13 will have further inter-helical distance due to the inhibitor (CHAMP design) and the BRET phenomenon will not perform due to the lack of close proximity between two helices. When we apply magnetic force to Mms13, the helices of the transmembrane protein will be pulled together and will induced the BRET phenomenon to emit fluorescence.

The CHAMP Design

CHAMP, the computed helical anti-membrane protein, is designed by one of the computational and genetic methods available to engineer antibody-like molecules that target the water-soluble regions of tansmembrane (TM) proteins (Hang Yin, et al., 2007).

In the project, we want to use this designed peptide, CHAMP sequence, to inhibit the tight interaction between two helices of membrane protein Mms13 so that we can successfully use mechanical force to change the conformation of Mms13 to induce the BiFC-based BRET phenomenon. The details of the CHAMP design is shown in protein modelling.

Our Constructs

We have six constructs for our design including both positive and negative controls.

Modeling For Optomagnetic Design

Though we have already done the design part of our project, we may be challenged by whether it can function in reality or not. We consulted with Professor Chun-Min Lo who has a professional background in biomechanics. One of his research interests is to apply magnetic force on the super magnetic particles contact on the cell membrane and measure the cell’s morphology and biomechanics to study the growth of cells. After we told him about our project and our final goal to achieve, he showed interest and was willing to help us in calculating and modeling our optomagnetic design and he also generously supplied electromagnets, a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by the flow of electric current, in his lab. We then modeled and calculated the force and magnetic field applied to the magnetic bacteria by using Professor Chun-Min Lo’s devices. (CM Lo, et al., 1998)

Activation-Required Magnetic Force

We calculated the force per unit volume of magnetosome by electronic balance, and also from the measured field of the permanent magnet. (Glogauer and Ferrier, 1998) The magnitude of the magnetic force per unit volume of iron oxide beads would be

Where M is the magnetization of the beads and δBz/δz is the gradient of the magnetic field along the normal line to the center of the pole face.

The magnetosome crystal is known to have high chemical purity so its magnetization can reach to the saturation limit for 3*105 A/m. The average diameter of the magnetosome is 46 nm in magnetic bacteria, so the volume per bead will be 4.077*10-22 m3. By calculating the data in the paper, we discovered that the cell can have very large scale of deformation when only around 2 nN is applied. With just 2 nN force, we can that track that cell and we can then trace back to the gradient of the magnetic field we should apply to the bacteria.

The average number of magnetosomes in magnetic bacteria is 20 particles. We should apply 2 nN/20=0.1 nN to one magnetosome. Dividing this by the total magnetosome volume (4.077*10-22 m3), there would be 0.1 nN / (4.077*10-22 m3)≈2.453*1011 N/m3 for force per volume. The gradient we need can be measured by dividing the force applied per volume to the saturated magnetization, which is: (2.453*1011 N/m3)/(3*105 A/m)≈8.176*105 T/m.

However, we certainly do not need the high gradient of up to 8.176*105 T/m. Because the need to pull the membrane and change the conformation of proteins would not require that much force. If the devices we apply now would not strong enough to change Mms13’s conformation, there is still nothing to worry about because we can add more turns per unit length of electromagnet to increase the magnetic gradient and thus induce stronger force to fulfill our goal.

References

- Johan Bacart, Caroline Corbel, Ralf Jockers, Stéphane Bach, Cyril Couturier Dr. (2008) The BRET technology and its application to screening assays. Biotechnology Journal Volume 3, Issue 3: 311–324

- Kevin D G Pfleger, Karin A Eidne. (2006) Illuminating insights into protein-protein interactions using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). Nature Methods 3:165 - 174

- Tom K. Kerppola. (2008) Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) Analysis as a Probe of Protein Interactions in Living Cells. Annu Rev Biophys 37: 465–487.

- Hang Yin, Joanna S. Slusky, Bryan W. Berger, Robin S. Walters, Gaston Vilaire, Rustem I. Litvinov, James D. Lear, Gregory A. Caputo, Joel S. Bennett, William F. DeGrado (2007). Supporting Online Material for Computational Design of Peptides That Target Transmembrane Helices. Science 315, 1817.

- J. S. Slusky, H. Yin and W. F. DeGrado. (2009) Understanding Membrane Proteins. How to Design Inhibitors of Transmembrane Protein—Protein Interactions. PROTEIN ENGINEERING Nucleic Acids and Molecular Biology 22, 315-337.

- Michael Glogauer and J. Ferrier. (1998) A new method for application of force to cells via ferric oxide beads. PFLÜGERS ARCHIV EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSIOLOGY 435, 2:320-327.

- Chun-Min Lo, Michael Glogauer, Marisa Rossi and J. Ferrier. (1998) Cell-substrate separation: effect of applied force and temperature. EUROPEAN BIOPHYSICS JOURNAL 27, 1: 9-17

- Hayden Huang, Roger D. Kamm, and Richard T. Lee. (2004) Cell mechanics and mechanotransduction: pathways, probes, and physiology. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1–C11.

- Joseph N. Fass and David J. Odde. (2003) Tensile Force-Dependent Neurite Elicitation via Anti-b1 Integrin Antibody-Coated Magnetic Beads. Biophysical Journal Volume 85:623–636 623.

- Hayden Huang, Jeremy Sylvan, Maxine Jonas, Rita Barresi, Peter T. C. So, Kevin P. Campbell, and Richard T. Lee. (2005) Cell stiffness and receptors: evidence for cytoskeletal subnetworks. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C72–C80.

"

"