Team:Osaka/Project

From 2011.igem.org

(→2. Detection of DNA damage) |

|||

| (39 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Osaka}} | {{Osaka}} | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| - | + | <html> | |

| - | + | <style type="text/css"> | |

| - | < | + | <!-- |

| - | + | ul {list-style:disc;} | |

| - | </ | + | dt {font-weight:bold;} |

| - | < | + | dd {margin:0 0 0 0;} |

| - | + | --> | |

| - | + | </style> | |

| - | + | </html> | |

| - | + | <div class="padding"> | |

| - | < | + | |

| - | + | ||

== Project Details== | == Project Details== | ||

| - | === | + | === DNA damage tolerance=== |

| - | [[File:deinococcus.jpg| | + | ==== <i>D. radiodurans</i> ==== |

| + | [[File:deinococcus.jpg|200px|right|''D.radiodurans'']] | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| - | The bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans shows remarkable resistance to a range of damage caused by ionizing radiation, desiccation, UV radiation, oxidizing agents, and electrophilic mutagens.It is an | + | The bacterium ''Deinococcus radiodurans'' shows remarkable resistance to a range of DNA damage caused by ionizing radiation, desiccation, UV radiation, oxidizing agents, and electrophilic mutagens. It is an aerobically-growing bacterium that is most famous for its extreme resistance to ionizing radiation; it not only can survive acute exposures to gamma radiation that exceed 15,000 Gy, but it can also grow continuously in the presence of chronic radiation (60 Gy/hour) without any effect on its growth rate or ability to express cloned genes. For comparison, <i>E. coli</i> can withstand up to 200 Gy, and an acute exposure of just 5-10 Gy is lethal to a human being.</p> |

| + | <p>We explored various genes from <i>D. radiodurans</i>, implicated in its remarkable DNA damage resistance. By BioBricking selected genes and transforming them into <i>E. coli</i>, we hoped to confer additional DNA damage tolerance to the host cells.</p> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | ==== Radiotolerance genes ==== | |

| + | *'''PprI''' | ||

| + | PprI, which is unique to ''D. radiodurans'', is invoked by present data as the most important protein for radiation response mechanism. | ||

| + | PprI can significantly and specifically induce the gene expression of recA and pprA and enhance the enzyme | ||

| + | activities of catalases. These results strongly suggest that PprI plays a crucial role in regulating multiple DNA repair and protection | ||

| + | pathways in response to radiation stress. | ||

| - | + | *'''PprA''' | |

| - | + | A pleiotropic protein promoting DNA repair, its role in radiation resistance of ''Deinococcus radiodurans'' | |

| - | + | was demonstrated. | |

| + | PprA preferentially binds to double-stranded DNA carrying strand breaks, inhibits ''E. coli'' exonuclease III activity, and stimulates the DNA end-joining reaction catalysed by ATP-dependent and NAD-dependent DNA ligases. These | ||

| + | results suggest that ''D. radiodurans'' has a radiationinduced non-homologous end-joining repair mechanism | ||

| + | in which PprA plays a critical role. | ||

| - | + | *'''PprM''' | |

| + | PprM (a modulator of the PprI-dependent DNA damage response) is a homolog of cold shock protein (Csp). PprM regulates the induction of PprA but not that of RecA. PprM belongs in a distinct clade of a subfamily together with Csp homologs from ''D. geothermalis'' and ''Thermus thermophilus''. | ||

| + | PprM plays an important role in the induction of RecA and PprA and is involved in the unique radiation response mechanism controlled by PprI in ''D. radiodurans''. | ||

| - | === | + | *'''RecA''' |

| + | The ''D. radiodurans'' RecA protein has been characterized and its gene has been sequenced; it shows greater than 50% identity to the ''E. coli'' RecA protein. ''D. radiodurans'' recA mutants are highly sensitive to UV and ionizing radiation. In this context, early work by Carroll et al (1996) reported that ''E. coli'' RecA did not complement an IR-sensitive ''D. radiodurans'' recA point-mutant (rec30) and that expression of ''D. radiodurans'' RecA in ''E. coli'' was lethal. More recently, however, it has been reported that <I>E. coli</I> recA can provide partial complementation to a ''D. radiodurans'' recA null mutant (Schlesinger, 2007). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === DNA damage detection === | ||

| + | ==== SOS response ==== | ||

[[File:SOS response.png|left|sos responce|300px]] | [[File:SOS response.png|left|sos responce|300px]] | ||

| - | <p>If DNA is damaged | + | <p>If DNA is significantly damaged (eg by exposure to UV radiation or chemicals), synthesis of several DNA damage-related proteins occurs quickly. |

| - | This reaction to DNA damage is SOS response.</p> | + | This reaction to DNA damage is the SOS response.</p> |

| - | <p>RecA is a 38 kilodalton Escherichia coli protein essential for the repair and maintenance of DNA. RecA has multiple activities, all related to DNA repair. In the bacterial SOS response, it has a co-protease function in the autocatalytic cleavage of the LexA repressor and the λ repressor. LexA is expressed constitutively and prevents damage-related proteins | + | <p>RecA is a 38 kilodalton <I>Escherichia coli</I> protein essential for the repair and maintenance of DNA. RecA has multiple activities, all related to DNA repair. In the bacterial SOS response, it has a co-protease function in the autocatalytic cleavage of the LexA repressor and the λ repressor. LexA is expressed constitutively and prevents expression of damage-related proteins by binding to SOS box as a repressor. RecA is activated by binding to single-stranded DNA, and the activated RecA then turns on LexA protease activity. Self-cleavage of LexA derepresses the expression of damage-related proteins enabling a response to be mounted. </p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>We decided to employ the promoter of the RecA gene ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_J22106 BBa J22106]) to detect DNA damage. While RecA is an inducer of SOS genes, it itself is an SOS gene that is auto-induced upon DNA damage. Expression of genes downstream of this promoter is induced by DNA damage.</p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | Bio-dosimeter must | + | |

| + | ==== Lycopene biosynthesis ==== | ||

| + | [[File:Pigment.jpg|280px|right]] | ||

| + | <p>Our Bio-dosimeter must have some sort of visible output to alert users to radioactivity (detected as DNA damage). In a previous iGEM project, "colrcoli", we attempted to use <I>E.coli</I> as a paint tool. To that end, we examined biosynthesis of carotenoid pigments as a way of producing color. Here, we attempted to use biosynthesis of the carotenoid lycopene as a reporter for DNA damage.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Carotenoid is a family of natural pigments. Many plants such as fruits and vegetables contain these pigments. For example, tomato has lycopene(red), carrot has carotene(orange). Xanthophyll(yellow) is found in almost all plants.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Biosynthesis of carotenoid pigments starts from FPP(FARNESYL DIPHOSPHATE). FPP is formed from isopentenylpyrophosphate(IPP) and dimethylallylpyrophosphate(DMAPP), which can be biologically produced by two distinct pathways, the mevalonate and non-mevalonate pathways. In <i>E.coli</i>, FPP is formed through the non-mevalonate pathway. By the introduction of heterologous enzymatic genes colorless FPP is then converted to orange-red lycopene, which has a peak absorbance at 407nm that is easily measured. </p> | ||

| + | <p>As shown in the figure on the right, the heterologous enzymes CrtE, CrtB, CrtI were introduced into <i>E. coli</i> to complete the biosynthesis of lycopene. We used a lycopene biosynthetic gene cluster provided by 2009 Cambridge (<partinfo>K274100</partinfo>).<br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

=== References=== | === References=== | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| - | <li>[1] Y. Hua et al., “PprI: a general switch responsible for extreme radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 306, no. 2, pp. 354-360, Jun. 2003.</li> | + | <li>[1] Y. Hua et al., “PprI: a general switch responsible for extreme radioresistance of ''Deinococcus radiodurans'',” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 306, no. 2, pp. 354-360, Jun. 2003.</li> |

| - | <li>G. Gao, B. Tian, L. Liu, D. Sheng, B. Shen, and Y. Hua, “Expression of Deinococcus radiodurans PprI enhances the radioresistance of Escherichia coli,” DNA Repair, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 1419-1427, Dec. 2003.</li> | + | <li>G. Gao, B. Tian, L. Liu, D. Sheng, B. Shen, and Y. Hua, “Expression of ''Deinococcus radiodurans'' PprI enhances the radioresistance of ''Escherichia coli'',” DNA Repair, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 1419-1427, Dec. 2003.</li> |

| - | <li>I. Narumi, K. Satoh, S. Cui, T. Funayama, S. Kitayama, and H. Watanabe, “PprA: a novel protein from Deinococcus radiodurans that stimulates DNA ligation,” Molecular Microbiology, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 278-285, Oct. 2004.</li> | + | <li>I. Narumi, K. Satoh, S. Cui, T. Funayama, S. Kitayama, and H. Watanabe, “PprA: a novel protein from ''Deinococcus radiodurans'' that stimulates DNA ligation,” Molecular Microbiology, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 278-285, Oct. 2004.</li> |

| - | <li>S. Kota and H. S. Misra, “PprA: A protein implicated in radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans stimulates catalase activity in Escherichia coli,” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 790-796, Oct. 2006.</li> | + | <li>S. Kota and H. S. Misra, “PprA: A protein implicated in radioresistance of ''Deinococcus radiodurans'' stimulates catalase activity in ''Escherichia coli'',” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 790-796, Oct. 2006.</li> |

| - | <li>H. Lu et al., | + | <li>H. Lu et al., “''Deinococcus radiodurans'' PprI switches on DNA damage response and cellular survival networks after radiation damage,” Molecular & Cellular Proteomics: MCP, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 481-494, Mar. 2009.</li> |

| - | <li>H. Ohba, K. Satoh, H. Sghaier, T. Yanagisawa, and I. Narumi, “Identification of PprM: a modulator of the PprI-dependent DNA damage response in Deinococcus radiodurans,” Extremophiles: Life Under Extreme Conditions, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 471-479, May 2009.</li> | + | <li>H. Ohba, K. Satoh, H. Sghaier, T. Yanagisawa, and I. Narumi, “Identification of PprM: a modulator of the PprI-dependent DNA damage response in ''Deinococcus radiodurans'',” Extremophiles: Life Under Extreme Conditions, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 471-479, May 2009.</li> |

</ol> | </ol> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 23:40, 28 October 2011

Project Details

DNA damage tolerance

D. radiodurans

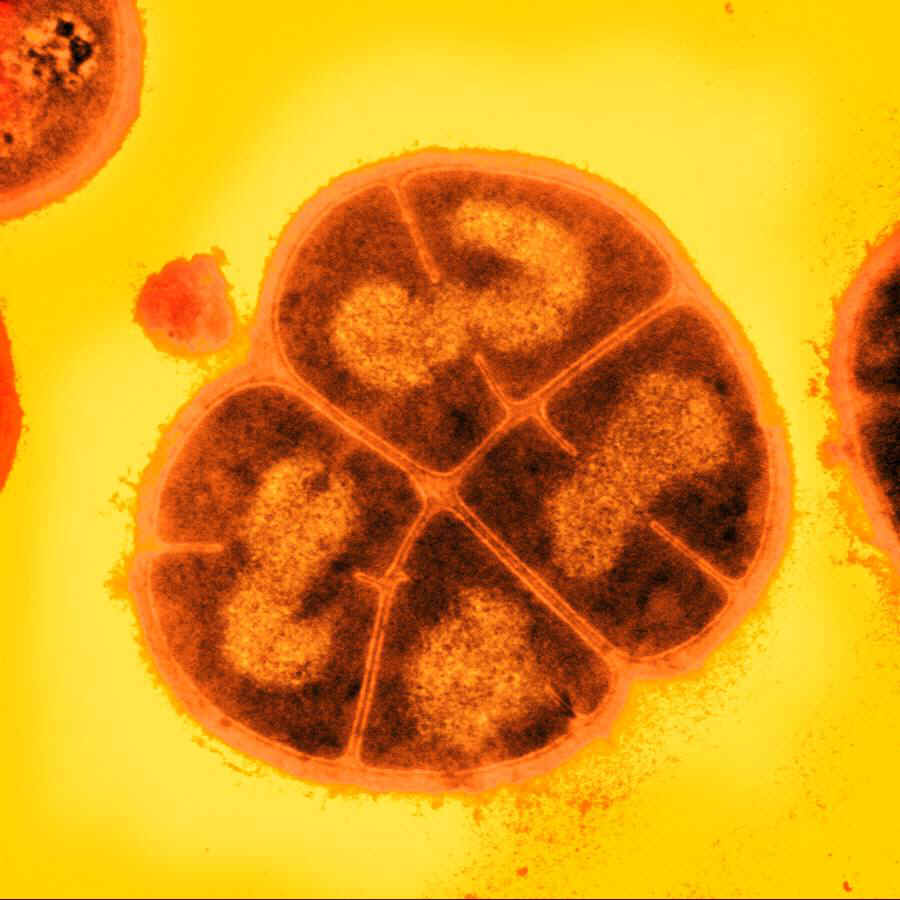

The bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans shows remarkable resistance to a range of DNA damage caused by ionizing radiation, desiccation, UV radiation, oxidizing agents, and electrophilic mutagens. It is an aerobically-growing bacterium that is most famous for its extreme resistance to ionizing radiation; it not only can survive acute exposures to gamma radiation that exceed 15,000 Gy, but it can also grow continuously in the presence of chronic radiation (60 Gy/hour) without any effect on its growth rate or ability to express cloned genes. For comparison, E. coli can withstand up to 200 Gy, and an acute exposure of just 5-10 Gy is lethal to a human being.

We explored various genes from D. radiodurans, implicated in its remarkable DNA damage resistance. By BioBricking selected genes and transforming them into E. coli, we hoped to confer additional DNA damage tolerance to the host cells.

Radiotolerance genes

- PprI

PprI, which is unique to D. radiodurans, is invoked by present data as the most important protein for radiation response mechanism. PprI can significantly and specifically induce the gene expression of recA and pprA and enhance the enzyme activities of catalases. These results strongly suggest that PprI plays a crucial role in regulating multiple DNA repair and protection pathways in response to radiation stress.

- PprA

A pleiotropic protein promoting DNA repair, its role in radiation resistance of Deinococcus radiodurans was demonstrated. PprA preferentially binds to double-stranded DNA carrying strand breaks, inhibits E. coli exonuclease III activity, and stimulates the DNA end-joining reaction catalysed by ATP-dependent and NAD-dependent DNA ligases. These results suggest that D. radiodurans has a radiationinduced non-homologous end-joining repair mechanism in which PprA plays a critical role.

- PprM

PprM (a modulator of the PprI-dependent DNA damage response) is a homolog of cold shock protein (Csp). PprM regulates the induction of PprA but not that of RecA. PprM belongs in a distinct clade of a subfamily together with Csp homologs from D. geothermalis and Thermus thermophilus. PprM plays an important role in the induction of RecA and PprA and is involved in the unique radiation response mechanism controlled by PprI in D. radiodurans.

- RecA

The D. radiodurans RecA protein has been characterized and its gene has been sequenced; it shows greater than 50% identity to the E. coli RecA protein. D. radiodurans recA mutants are highly sensitive to UV and ionizing radiation. In this context, early work by Carroll et al (1996) reported that E. coli RecA did not complement an IR-sensitive D. radiodurans recA point-mutant (rec30) and that expression of D. radiodurans RecA in E. coli was lethal. More recently, however, it has been reported that E. coli recA can provide partial complementation to a D. radiodurans recA null mutant (Schlesinger, 2007).

DNA damage detection

SOS response

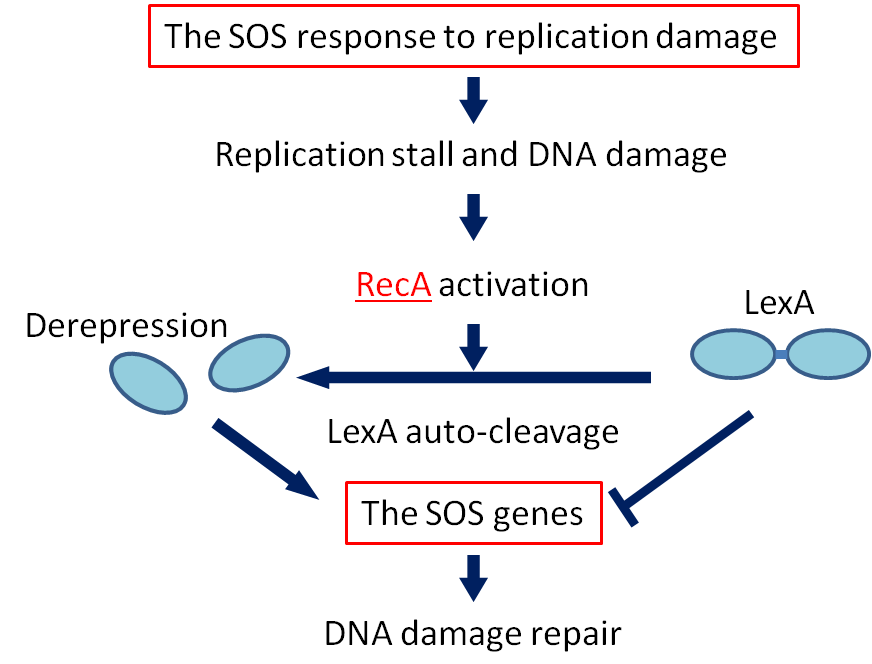

If DNA is significantly damaged (eg by exposure to UV radiation or chemicals), synthesis of several DNA damage-related proteins occurs quickly. This reaction to DNA damage is the SOS response.

RecA is a 38 kilodalton Escherichia coli protein essential for the repair and maintenance of DNA. RecA has multiple activities, all related to DNA repair. In the bacterial SOS response, it has a co-protease function in the autocatalytic cleavage of the LexA repressor and the λ repressor. LexA is expressed constitutively and prevents expression of damage-related proteins by binding to SOS box as a repressor. RecA is activated by binding to single-stranded DNA, and the activated RecA then turns on LexA protease activity. Self-cleavage of LexA derepresses the expression of damage-related proteins enabling a response to be mounted.

We decided to employ the promoter of the RecA gene ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_J22106 BBa J22106]) to detect DNA damage. While RecA is an inducer of SOS genes, it itself is an SOS gene that is auto-induced upon DNA damage. Expression of genes downstream of this promoter is induced by DNA damage.

Lycopene biosynthesis

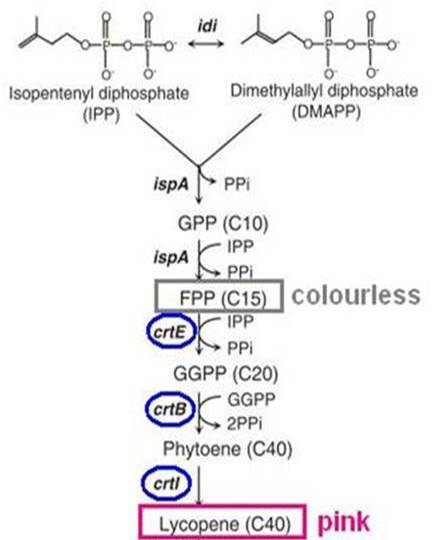

Our Bio-dosimeter must have some sort of visible output to alert users to radioactivity (detected as DNA damage). In a previous iGEM project, "colrcoli", we attempted to use E.coli as a paint tool. To that end, we examined biosynthesis of carotenoid pigments as a way of producing color. Here, we attempted to use biosynthesis of the carotenoid lycopene as a reporter for DNA damage.

Carotenoid is a family of natural pigments. Many plants such as fruits and vegetables contain these pigments. For example, tomato has lycopene(red), carrot has carotene(orange). Xanthophyll(yellow) is found in almost all plants.

Biosynthesis of carotenoid pigments starts from FPP(FARNESYL DIPHOSPHATE). FPP is formed from isopentenylpyrophosphate(IPP) and dimethylallylpyrophosphate(DMAPP), which can be biologically produced by two distinct pathways, the mevalonate and non-mevalonate pathways. In E.coli, FPP is formed through the non-mevalonate pathway. By the introduction of heterologous enzymatic genes colorless FPP is then converted to orange-red lycopene, which has a peak absorbance at 407nm that is easily measured.

As shown in the figure on the right, the heterologous enzymes CrtE, CrtB, CrtI were introduced into E. coli to complete the biosynthesis of lycopene. We used a lycopene biosynthetic gene cluster provided by 2009 Cambridge (<partinfo>K274100</partinfo>).

References

- [1] Y. Hua et al., “PprI: a general switch responsible for extreme radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 306, no. 2, pp. 354-360, Jun. 2003.

- G. Gao, B. Tian, L. Liu, D. Sheng, B. Shen, and Y. Hua, “Expression of Deinococcus radiodurans PprI enhances the radioresistance of Escherichia coli,” DNA Repair, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 1419-1427, Dec. 2003.

- I. Narumi, K. Satoh, S. Cui, T. Funayama, S. Kitayama, and H. Watanabe, “PprA: a novel protein from Deinococcus radiodurans that stimulates DNA ligation,” Molecular Microbiology, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 278-285, Oct. 2004.

- S. Kota and H. S. Misra, “PprA: A protein implicated in radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans stimulates catalase activity in Escherichia coli,” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 790-796, Oct. 2006.

- H. Lu et al., “Deinococcus radiodurans PprI switches on DNA damage response and cellular survival networks after radiation damage,” Molecular & Cellular Proteomics: MCP, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 481-494, Mar. 2009.

- H. Ohba, K. Satoh, H. Sghaier, T. Yanagisawa, and I. Narumi, “Identification of PprM: a modulator of the PprI-dependent DNA damage response in Deinococcus radiodurans,” Extremophiles: Life Under Extreme Conditions, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 471-479, May 2009.

"

"