Team:Harvard/Technology/MAGE

From 2011.igem.org

(→Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE): Editing the Bacterial Genome) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{:Team:Harvard/Template:TechBar}} | {{:Team:Harvard/Template:TechBar}} | ||

{{:Team:Harvard/Template:TechGrayBar}} | {{:Team:Harvard/Template:TechGrayBar}} | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<div class="whitebox"> | <div class="whitebox"> | ||

| - | To see how we used MAGE to build our selection strain, go to our [https://2011.igem.org/Team:Harvard/ | + | To see how we used MAGE to build our selection strain, go to our [https://2011.igem.org/Team:Harvard/Project/Test#Building_the_selection_strain:_MAGE Test] page. |

| + | |||

| + | For a step-by-step procedure, see our [https://2011.igem.org/Team:Harvard/Protocols#MAGE MAGE Protocols]. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="whitebox"> | ||

| + | __NOTOC__ | ||

| + | =MAGE= | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:HARVmage.jpg|thumb|Each cell contains a different set of mutations, producing a heterogeneous population of rich diversity (denoted by distinct chromosomes in different cells). Degenerate oligo pools that target specific genomic positions enable the generation of a diverse set of sequences at each chromosomal location. (Wang et al)]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Summary (Adapted from Wang et al)<sup>[[#References|[2]]],[[#References|[3]]]</sup>== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The breadth of genomic diversity found among organisms in nature allows populations to adapt to diverse environments. However, genomic diversity is difficult to generate in the laboratory and new phenotypes do not easily arise on practical timescales. Although in vitro and directed evolution methods have created genetic variants with usefully altered phenotypes, these methods are limited to laborious and serial manipulation of single genes and are not used for parallel and continuous directed evolution of gene networks or genomes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) is a new method for large-scale programming and evolution of cells. MAGE simultaneously targets many locations on the chromosome, thus producing combinatorial genomic diversity. Because the process is cyclical and scalable, MAGE facilitates rapid and continuous generation of a diverse set of genetic changes (mismatches, insertions, deletions). This multiplex approach embraces engineering in the context of evolution by expediting the design and evolution of organisms with new and improved properties. | ||

| + | |||

| + | MAGE provides a highly efficient, inexpensive and automated solution to simultaneously modify many genomic locations (for example, genes, regulatory regions) across different length scales, from the nucleotide to the genome level. | ||

| + | |||

| - | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="whitebox"> | <div class="whitebox"> | ||

| + | |||

=Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE): Editing the Bacterial Genome= | =Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE): Editing the Bacterial Genome= | ||

| Line 20: | Line 34: | ||

==Oligo Design:== | ==Oligo Design:== | ||

| - | |||

The design of the MAGE oligo is critical to the success of the procedure. Typically 90 bases long, with the first four 5’ bases phosphorothioated, the oligo must match the sequence of the region of interest (with the exception of the desired mutations) such that it will be incorporated into the lagging strand during replication. To determine which genomic strand to use as the template, it is necessary to determine whether the gene is in replichore 1 or 2 and whether it is on the + or - strand (see Figure 2). The mismatches, insertions, and/or deletions in the sequence must be centered on the oligo, and there should be as few alterations as possible, since each change will lower the efficiency of incorporation into the genome (see Figure 3). | The design of the MAGE oligo is critical to the success of the procedure. Typically 90 bases long, with the first four 5’ bases phosphorothioated, the oligo must match the sequence of the region of interest (with the exception of the desired mutations) such that it will be incorporated into the lagging strand during replication. To determine which genomic strand to use as the template, it is necessary to determine whether the gene is in replichore 1 or 2 and whether it is on the + or - strand (see Figure 2). The mismatches, insertions, and/or deletions in the sequence must be centered on the oligo, and there should be as few alterations as possible, since each change will lower the efficiency of incorporation into the genome (see Figure 3). | ||

| Line 28: | Line 41: | ||

[[File: HARVMAGEtech3.png|450px|Figure 3: Efficiency of incorporation for different types of sequence modifications]] | [[File: HARVMAGEtech3.png|450px|Figure 3: Efficiency of incorporation for different types of sequence modifications]] | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="whitebox"> | ||

| + | ==References:== | ||

| + | '''1.''' Harris H. Wang, Farren J. Isaacs, Peter A. Carr, Zachary Z. Sun, George Xu, Craig R. Forest, George M. Church. Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. (2009). ''Nature'', 460(7257):894-8. [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v460/n7257/full/nature08187.html] | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | '''2.''' Isaacs FJ, Carr PA, Wang HH, Lajoie MJ, Sterling B, Kraal L, Tolonen AC, Gianoulis TA, Goodman DB, Reppas NB, Emig CJ, Bang D, Hwang SJ, Jewett MC, Jacobson JM, Church GM. (2011). Precise manipulation of chromosomes in vivo enables genome-wide codon replacement. ''Science'', 333(6040):348-53. [http://www.sciencemag.org/content/333/6040/348.short] | |

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 00:56, 22 October 2011

Overview | MAGE | Chip-Based Synthesis | Lambda Red | Protocols

To see how we used MAGE to build our selection strain, go to our Test page.

For a step-by-step procedure, see our MAGE Protocols.

MAGE

Summary (Adapted from Wang et al)[2],[3]

The breadth of genomic diversity found among organisms in nature allows populations to adapt to diverse environments. However, genomic diversity is difficult to generate in the laboratory and new phenotypes do not easily arise on practical timescales. Although in vitro and directed evolution methods have created genetic variants with usefully altered phenotypes, these methods are limited to laborious and serial manipulation of single genes and are not used for parallel and continuous directed evolution of gene networks or genomes.

Multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) is a new method for large-scale programming and evolution of cells. MAGE simultaneously targets many locations on the chromosome, thus producing combinatorial genomic diversity. Because the process is cyclical and scalable, MAGE facilitates rapid and continuous generation of a diverse set of genetic changes (mismatches, insertions, deletions). This multiplex approach embraces engineering in the context of evolution by expediting the design and evolution of organisms with new and improved properties.

MAGE provides a highly efficient, inexpensive and automated solution to simultaneously modify many genomic locations (for example, genes, regulatory regions) across different length scales, from the nucleotide to the genome level.

Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE): Editing the Bacterial Genome

How MAGE works:

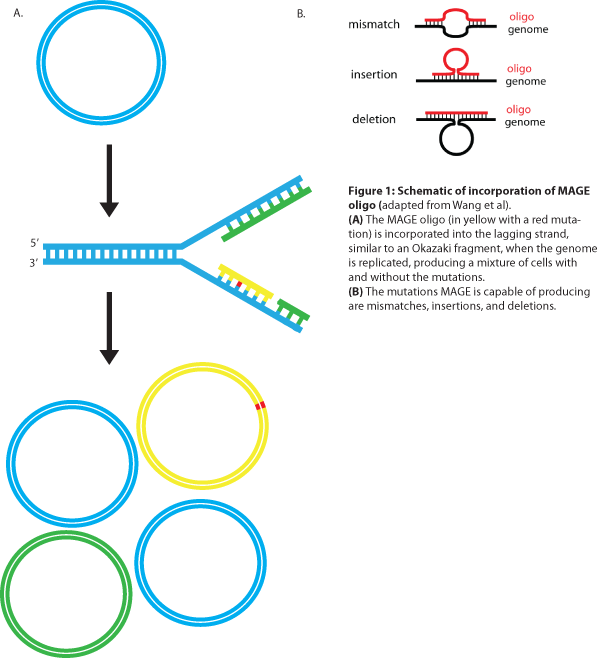

MAGE is a recently developed technique capable of editing the genome by making small changes in existing genomic sequences. This is accomplished by inserting single-stranded oligos that contain the desired mutations into the cell, and more than one gene can be targeted at a time simply by using multiple oligos. Mediated by λ-Red ssDNA-binding protein β, the oligos are incorporated into the lagging strand of the replication fork during DNA replication, creating a new allele that will spread through the population as the bacteria divide (see Figure 1). The efficiency of oligo incorporation depends on several factors, but the frequency of the allele can be increased by performing multiple rounds of MAGE on the same cell culture. Currently, researchers must perform each round by hand, a procedure requiring several hours, but automated processes are being developed to run many rounds of MAGE in succession. Together, these properties make MAGE a highly useful tool for synthetic biology, allowing researchers to easily modify the bacterial genome and generate diversity within a population.

Oligo Design:

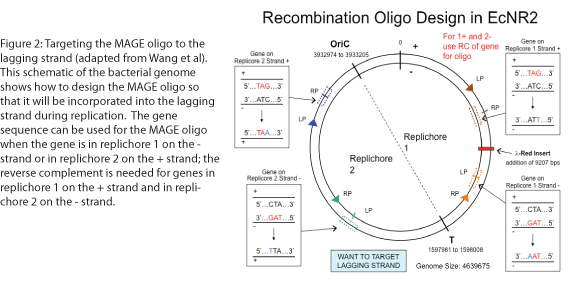

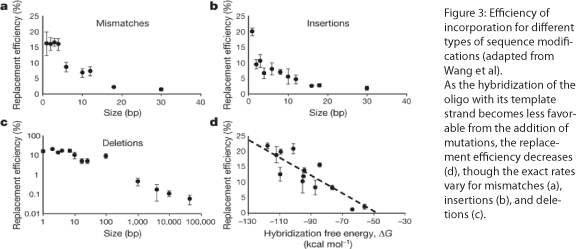

The design of the MAGE oligo is critical to the success of the procedure. Typically 90 bases long, with the first four 5’ bases phosphorothioated, the oligo must match the sequence of the region of interest (with the exception of the desired mutations) such that it will be incorporated into the lagging strand during replication. To determine which genomic strand to use as the template, it is necessary to determine whether the gene is in replichore 1 or 2 and whether it is on the + or - strand (see Figure 2). The mismatches, insertions, and/or deletions in the sequence must be centered on the oligo, and there should be as few alterations as possible, since each change will lower the efficiency of incorporation into the genome (see Figure 3).

References:

1. Harris H. Wang, Farren J. Isaacs, Peter A. Carr, Zachary Z. Sun, George Xu, Craig R. Forest, George M. Church. Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. (2009). Nature, 460(7257):894-8. [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v460/n7257/full/nature08187.html]

2. Isaacs FJ, Carr PA, Wang HH, Lajoie MJ, Sterling B, Kraal L, Tolonen AC, Gianoulis TA, Goodman DB, Reppas NB, Emig CJ, Bang D, Hwang SJ, Jewett MC, Jacobson JM, Church GM. (2011). Precise manipulation of chromosomes in vivo enables genome-wide codon replacement. Science, 333(6040):348-53. [http://www.sciencemag.org/content/333/6040/348.short]

"

"