Team:Glasgow/Biofilm/P. aeruginosa

From 2011.igem.org

Chris Wood (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (13 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

<h2><i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i></h2> | <h2><i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i></h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <a name="top"></a><h6> Contents</h6> | ||

| + | <ul> <a href="#biofilms"><i>P.aeruginosa</i> Biofilms</a></ul> | ||

| + | <ul> <a href="#properties"><i>Properties of <i>P. Aeruginosa Biofilms</i></a></ul> | ||

| + | <ul> <a href="#discoli">P. aeruginosa</i> in DISColi</a></ul> | ||

| + | <ul> <a href="#chassis">New Chassis</a></ul> | ||

| + | <ul> <a href="#ref2">References</a></ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h6>Biofilm forming organisms</h6> | ||

| + | <ul> <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:Glasgow/Biofilm/Nissle">E. coli Nissle 1917</a></ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h6> <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:Glasgow/BiofilmResults">Results obtained from experimentation</a></h6> | ||

| + | <h6><a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:Glasgow/Biofilm">Back to Biofilms</a></h6> | ||

| + | <h6><a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:Glasgow/Results">Back to Results</a></h6> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<table> | <table> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

| - | <p><i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> is an opportunistic pathogen of a wide range of | + | <p><i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> is an opportunistic pathogen of a wide range of organisms that includes humans. Normally it lives in soil and water however it can be found in skin flora and artificial environments like the surface of a catheter. It is a rod shaped gram-negative bacteria that has unipolar flagellae for motility. Although it is aerobic it can survive in hypoxic conditions leading some microbiologists to consider it a facultative anaerobe. <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> naturally produces the coloured pigments pyocyanin (blue-green), pyoverdine (yellow-green) and pyorubin (red-brown). (Todar, K 2011) |

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | As an opportunistic pathogen it can cause nosocomial infections most commonly in the elder or immunocompromised. Most can lead to infections of the kidneys, lung or urinary tracts which are had to treat with conventional antibiotics after it has formed biofilm biofilms.(Chen, S 2010) <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> is commonly found in the gut of humans where it exists in a benign state and does not express any toxins that cause organ damage. However low levels of phosphate have been found to trigger the production of these toxins. This is significant as after organ surgery levels of inorganic phosphate in the body falls. (Koppes, S 2009) | ||

</br> | </br> | ||

| - | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

| - | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/d/d6/PAglasgow.jpg" /> | + | <div><center><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/d/d6/PAglasgow.jpg" /></center></div> |

| + | <div><b>Figure 1: Electron micrograph of <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i>.</b> This image shows clearly the unipolar flagella that provide cellular motility pili that aid adhesion. Photo by Dennis Kunkel Microscopy</div> | ||

| + | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | <h6> <a href="#top">Return to top</a></h6> | ||

| - | <h2><i>P.aeruginosa</i> Biofilms</h2> | + | <a name="biofilms"></a><h2><i>P.aeruginosa</i> Biofilms</h2> |

<p> | <p> | ||

| - | <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa </i> is the standard organism for the investigation of biofilms, as it is very adept at forming them. This ability is mainly due to the production of exopolysaccharides (EPS), most notably the protein alginate, that is produced by the mucoid strains of <i>P. aeruginosa</i> and leads to the production of notably thicker and more stable biofilms,though it is not essential for biofilm formation</p> | + | <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> is the standard organism for the investigation of biofilms, as it is very adept at forming them. This ability is mainly due to the production of exopolysaccharides (EPS), most notably the protein alginate, that is produced by the mucoid strains of <i>P. aeruginosa</i> and leads to the production of notably thicker and more stable biofilms,though it is not essential for biofilm formation</p> |

<p>The strain that was chosen for this project is the wild type PA01 strain, that forms stable smooth, and more homogenous biofilms.</p> | <p>The strain that was chosen for this project is the wild type PA01 strain, that forms stable smooth, and more homogenous biofilms.</p> | ||

<div><img src="http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6179/6170658008_ee5d0dab3b.jpg"><p><font size="1" color="grey">Figure1: Biofilm architecture in muciod and non-mucoid P.aeruginosa strains. a) Typical biofilm architecture of the mucoid (alginate over-expressing) SG81 strain b)The smoother biofilm architecture typical of non-mucoid strains such as the wild type PA01 that was used in this project </font></p></div></br> | <div><img src="http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6179/6170658008_ee5d0dab3b.jpg"><p><font size="1" color="grey">Figure1: Biofilm architecture in muciod and non-mucoid P.aeruginosa strains. a) Typical biofilm architecture of the mucoid (alginate over-expressing) SG81 strain b)The smoother biofilm architecture typical of non-mucoid strains such as the wild type PA01 that was used in this project </font></p></div></br> | ||

| Line 34: | Line 54: | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

<img src="http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6177/6170913398_6e217cc778_m.jpg"/> | <img src="http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6177/6170913398_6e217cc778_m.jpg"/> | ||

| - | <p><font size="1" color="grey">Image 1: EM of P. aeruginosa biofilm, showing its densely packed structure </br>(courtesy of Dan Walker, University of Glasgow</font></p> | + | <p><font size="1" color="grey">Image 1: 1000x EM of P. aeruginosa biofilm, showing its densely packed structure </br>(courtesy of Dan Walker, University of Glasgow)</font></p> |

</td> | </td> | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

| - | <img src="http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6171/6170367511_51e5363dbd_m.jpg"/> | + | <img src="http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6171/6170367511_51e5363dbd_m.jpg" width="230" height="170"/> |

| - | <p><font size="1" color="grey"> Image 2: EM of E.coli for comparison. No fimbriae or EPS is visible. (courtesy of Rocky Mountain Laboratories)</font></p> | + | <p><font size="1" color="grey"> Image 2: 15,000x EM of E.coli for comparison. No fimbriae or EPS is visible. (courtesy of Rocky Mountain Laboratories)</font></p> |

</td> | </td> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | <h2> Properties of <i>P. Aeruginosa Biofilms</i></h2> | + | |

| + | <h6> <a href="#top">Return to top</a></h6> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <a name="properties"></a><h2> Properties of <i>P. Aeruginosa Biofilms</i></h2> | ||

<table> | <table> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 48: | Line 71: | ||

<b>Method</b> | <b>Method</b> | ||

<p>As we were trying to specifically disperse areas of biofilm it was necessary to establish a base rate of dispersal of the biofilm without using any of the dispersal mechanisms we designed. This would allow us to show quantitatively the increase in rate of dispersal that our different dispersal biobrick could generate when compared to a biofilm of non-transformed bacteria.</p> | <p>As we were trying to specifically disperse areas of biofilm it was necessary to establish a base rate of dispersal of the biofilm without using any of the dispersal mechanisms we designed. This would allow us to show quantitatively the increase in rate of dispersal that our different dispersal biobrick could generate when compared to a biofilm of non-transformed bacteria.</p> | ||

| + | <p>This assay is assuming that you are measuring the base rate of dispersal after transferring the biofilm into fresh media. This assay was developed with the prospect of using it to measure an induced increase in dispersal.</p> | ||

<p>To measure the base rate of dispersal glass slides were put into 50ml tubes containing 20ml of LB broth. The LB covered around a third of the glass slide, this is the area where the biofilm would form. The LB was then inoculated with 20μl of overnight culture of <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i>. These tubes were then left on a bench top shaker at room temperature for a set amount of time (time points ranged from 1hr to 48hrs). After the biofilm had grown its allotted time the glass slide was carefully removed and placed into a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB (which completely covered the biofilm) and left to allow the bacteria to disperse for 1hr. The slide was then transferred to a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB. The biofilm is scraped off the slide using a thin flexible spatula. At this point both the dispersed cell and the biofilm scrapings were sonicated to stop clumping and plated in serial dilutions.</p> | <p>To measure the base rate of dispersal glass slides were put into 50ml tubes containing 20ml of LB broth. The LB covered around a third of the glass slide, this is the area where the biofilm would form. The LB was then inoculated with 20μl of overnight culture of <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i>. These tubes were then left on a bench top shaker at room temperature for a set amount of time (time points ranged from 1hr to 48hrs). After the biofilm had grown its allotted time the glass slide was carefully removed and placed into a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB (which completely covered the biofilm) and left to allow the bacteria to disperse for 1hr. The slide was then transferred to a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB. The biofilm is scraped off the slide using a thin flexible spatula. At this point both the dispersed cell and the biofilm scrapings were sonicated to stop clumping and plated in serial dilutions.</p> | ||

</br></br> | </br></br> | ||

| Line 73: | Line 97: | ||

<b>Figure 2: <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> biofilm growth over time.</b> These photographs were taken after 1hr, 14hrs and 48hrs of biofilm growth. They were stained using a Grams stain method that is designed specifically to avoid sheer forces being applied to the delicate biofilm structure. Details of this method are included in the <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:Glasgow/Lab_Book"><i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> biofilms</a> lab book. | <b>Figure 2: <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> biofilm growth over time.</b> These photographs were taken after 1hr, 14hrs and 48hrs of biofilm growth. They were stained using a Grams stain method that is designed specifically to avoid sheer forces being applied to the delicate biofilm structure. Details of this method are included in the <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:Glasgow/Lab_Book"><i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> biofilms</a> lab book. | ||

</br> | </br> | ||

| - | <h2><i>P. aeruginosa</i> in DISColi</h2> | + | <h6> <a href="#top">Return to top</a></h6> |

| + | |||

| + | <a name="discoli"></a><h2><i>P. aeruginosa</i> in DISColi</h2> | ||

<p>Although <i>P. aeruginosa</i> forms biofilms admirably and quickly under a range of conditions, we decided against using it as a chassis in the DISColi project.</p> | <p>Although <i>P. aeruginosa</i> forms biofilms admirably and quickly under a range of conditions, we decided against using it as a chassis in the DISColi project.</p> | ||

<p>The disadvantages of working with <i>P. aeruginosa</i> are: | <p>The disadvantages of working with <i>P. aeruginosa</i> are: | ||

| Line 79: | Line 105: | ||

<p>-It is not suitable for transformation with most standard biobricks, which are intended for primary use in <i>E. coli</i> | <p>-It is not suitable for transformation with most standard biobricks, which are intended for primary use in <i>E. coli</i> | ||

<p>-It is naturally resistant to many antibiotics, making selection for transformants practically impossible</p> | <p>-It is naturally resistant to many antibiotics, making selection for transformants practically impossible</p> | ||

| - | <h2>New Chassis</h2> | + | <h6> <a href="#top">Return to top</a></h6> |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <a name="chassis"></a><h2>New Chassis</h2> | ||

<p>The decision not to use <i>P. aeruginosa</i> brought with it the obstacle of finding a new chassis that would form biofilm, but without any of the disadvantages of <i>P. aeruginosa</i>. Preferably a strain of <i>E. coli</i>...</p> | <p>The decision not to use <i>P. aeruginosa</i> brought with it the obstacle of finding a new chassis that would form biofilm, but without any of the disadvantages of <i>P. aeruginosa</i>. Preferably a strain of <i>E. coli</i>...</p> | ||

<p> We got lucky with <i>E. coli</i> Nissle 1917 : Our new biofilm chassis!</p> | <p> We got lucky with <i>E. coli</i> Nissle 1917 : Our new biofilm chassis!</p> | ||

<p><b>Continue to <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:Glasgow/Biofilm/Nissle"><i>E. coli</i> Nissle 1917</a></b></p> | <p><b>Continue to <a href="https://2011.igem.org/Team:Glasgow/Biofilm/Nissle"><i>E. coli</i> Nissle 1917</a></b></p> | ||

| - | < | + | <h6> <a href="#top">Return to top</a></h6> |

| - | < | + | |

| + | |||

| + | <a name="ref2"></a><h2>References</h2> | ||

<p>Flemming, H. & Wingende J., 2010. The Biofilm Matrix. Nature Reviews Microbiology 8, 623-633 </p> | <p>Flemming, H. & Wingende J., 2010. The Biofilm Matrix. Nature Reviews Microbiology 8, 623-633 </p> | ||

| + | <Chen, S "Pseudomonas Infection", Medscape, 2010, "http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/970904-overview" | ||

<p>Drenkard,E. & Frederick M. Ausube | <p>Drenkard,E. & Frederick M. Ausube | ||

| + | <p>Koppes, S "Research could lead to new non-antibiotic drugs to counter hospital infections" University of Chicago press release, 2009, "http://news.uchicago.edu/article/2009/04/14/research-could-lead-new-non-antibiotic-drugs-counter-hospital-infections" | ||

| + | <p>Todar, K "Pseudomonas aeruginosa", Online Encyclopaedia of Bacteriology, 2011, "http://textbookofbacteriology.net/pseudomonas.html" | ||

| + | <h6> <a href="#top">Return to top</a></h6> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 02:48, 22 September 2011

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Contents

Biofilm forming organisms

Results obtained from experimentation

Back to Biofilms

Back to Results

|

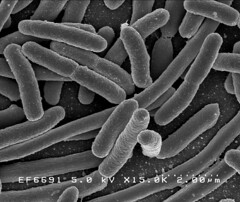

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen of a wide range of organisms that includes humans. Normally it lives in soil and water however it can be found in skin flora and artificial environments like the surface of a catheter. It is a rod shaped gram-negative bacteria that has unipolar flagellae for motility. Although it is aerobic it can survive in hypoxic conditions leading some microbiologists to consider it a facultative anaerobe. Pseudomonas aeruginosa naturally produces the coloured pigments pyocyanin (blue-green), pyoverdine (yellow-green) and pyorubin (red-brown). (Todar, K 2011) As an opportunistic pathogen it can cause nosocomial infections most commonly in the elder or immunocompromised. Most can lead to infections of the kidneys, lung or urinary tracts which are had to treat with conventional antibiotics after it has formed biofilm biofilms.(Chen, S 2010) Pseudomonas aeruginosa is commonly found in the gut of humans where it exists in a benign state and does not express any toxins that cause organ damage. However low levels of phosphate have been found to trigger the production of these toxins. This is significant as after organ surgery levels of inorganic phosphate in the body falls. (Koppes, S 2009) |

Figure 1: Electron micrograph of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This image shows clearly the unipolar flagella that provide cellular motility pili that aid adhesion. Photo by Dennis Kunkel Microscopy

|

Return to top

P.aeruginosa Biofilms

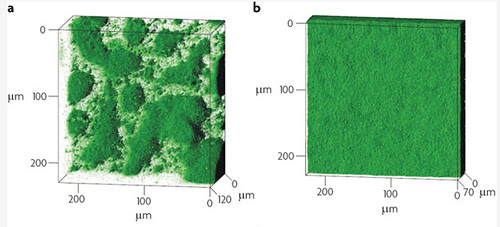

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the standard organism for the investigation of biofilms, as it is very adept at forming them. This ability is mainly due to the production of exopolysaccharides (EPS), most notably the protein alginate, that is produced by the mucoid strains of P. aeruginosa and leads to the production of notably thicker and more stable biofilms,though it is not essential for biofilm formation

The strain that was chosen for this project is the wild type PA01 strain, that forms stable smooth, and more homogenous biofilms.

Figure1: Biofilm architecture in muciod and non-mucoid P.aeruginosa strains. a) Typical biofilm architecture of the mucoid (alginate over-expressing) SG81 strain b)The smoother biofilm architecture typical of non-mucoid strains such as the wild type PA01 that was used in this project

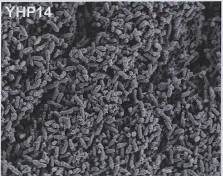

It has long been postulated that P.aeruginosa has significant resistance to a wide range of antibiotics because of it's ability to form sturdy, resistant biofilms. Drenkard & Ausube showed that biofilm formation is strongly correlated to antibiotic resistance, allowing P.aeruginosa to thrive in almost any environment.

Image 1: 1000x EM of P. aeruginosa biofilm, showing its densely packed structure (courtesy of Dan Walker, University of Glasgow) |

Image 2: 15,000x EM of E.coli for comparison. No fimbriae or EPS is visible. (courtesy of Rocky Mountain Laboratories) |

Return to top

Properties of P. Aeruginosa Biofilms

|

Method

As we were trying to specifically disperse areas of biofilm it was necessary to establish a base rate of dispersal of the biofilm without using any of the dispersal mechanisms we designed. This would allow us to show quantitatively the increase in rate of dispersal that our different dispersal biobrick could generate when compared to a biofilm of non-transformed bacteria. This assay is assuming that you are measuring the base rate of dispersal after transferring the biofilm into fresh media. This assay was developed with the prospect of using it to measure an induced increase in dispersal. To measure the base rate of dispersal glass slides were put into 50ml tubes containing 20ml of LB broth. The LB covered around a third of the glass slide, this is the area where the biofilm would form. The LB was then inoculated with 20μl of overnight culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These tubes were then left on a bench top shaker at room temperature for a set amount of time (time points ranged from 1hr to 48hrs). After the biofilm had grown its allotted time the glass slide was carefully removed and placed into a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB (which completely covered the biofilm) and left to allow the bacteria to disperse for 1hr. The slide was then transferred to a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB. The biofilm is scraped off the slide using a thin flexible spatula. At this point both the dispersed cell and the biofilm scrapings were sonicated to stop clumping and plated in serial dilutions. |

Figure 1: Number of viable cells in biofilm compared to number of cells dispersed from the biofilm in one hour. The base rate of dispersal remains roughly proportional to the number of cells in the biofilm. The information for the time point hour 14 for the biofilm was not available. |

To make the images of biofilm formation, biofilms were formed on glass slides inserted into 50ml tubes. The tube was filled with 20ml of LB broth and inoculated with 20μl of over night culture of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. The biofilms were left to form for the time indicated on the images.

Results The number of cells that dispersed from the biofilm seemed to be proportional to the number of cells in the biofilm with a ratio of roughly 5 dispersed:1 in biofilm. Figure 1 shows the number of dispersed cells when compared to the number of cells in the biofilm in both a graph and a table. Figure 2: Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth over time. These photographs were taken after 1hr, 14hrs and 48hrs of biofilm growth. They were stained using a Grams stain method that is designed specifically to avoid sheer forces being applied to the delicate biofilm structure. Details of this method are included in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms lab book.

Figure 2: Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth over time. These photographs were taken after 1hr, 14hrs and 48hrs of biofilm growth. They were stained using a Grams stain method that is designed specifically to avoid sheer forces being applied to the delicate biofilm structure. Details of this method are included in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms lab book.

Return to top

P. aeruginosa in DISColi

Although P. aeruginosa forms biofilms admirably and quickly under a range of conditions, we decided against using it as a chassis in the DISColi project.

The disadvantages of working with P. aeruginosa are:

-It is difficult to transform, and would require a shuttle vector we had no access to

-It is not suitable for transformation with most standard biobricks, which are intended for primary use in E. coli

-It is naturally resistant to many antibiotics, making selection for transformants practically impossible

Return to top

New Chassis

The decision not to use P. aeruginosa brought with it the obstacle of finding a new chassis that would form biofilm, but without any of the disadvantages of P. aeruginosa. Preferably a strain of E. coli...

We got lucky with E. coli Nissle 1917 : Our new biofilm chassis!

Continue to E. coli Nissle 1917

Return to top

References

Flemming, H. & Wingende J., 2010. The Biofilm Matrix. Nature Reviews Microbiology 8, 623-633

Koppes, S "Research could lead to new non-antibiotic drugs to counter hospital infections" University of Chicago press release, 2009, "http://news.uchicago.edu/article/2009/04/14/research-could-lead-new-non-antibiotic-drugs-counter-hospital-infections"

Todar, K "Pseudomonas aeruginosa", Online Encyclopaedia of Bacteriology, 2011, "http://textbookofbacteriology.net/pseudomonas.html"

"

"