Team:Glasgow/Results/Nissle

From 2011.igem.org

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

<h2>Methods</h2> | <h2>Methods</h2> | ||

| - | <p>Since our project was to examine the dispersal or fixation of a biofilm, we were in need of a chassis that had the ability to form them. Originally <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> was considered as a chassis, but it was quickly discarded. We found our chassis in <i>E.coli</i> Nissle 1917. It is non-pathogenic, and unlike <i>P.aeruginosa</i> it does not require a shuttle vector. However, the cells were not readily available, and had to be extracted from <i>Mutaflor</i> Tablets. We selected for the desired cells using MacConkey's agar </p> | + | <p>Since our project was to examine the dispersal or fixation of a biofilm, we were in need of a chassis that had the ability to form them. Originally <i>Pseudomonas aeruginosa</i> was considered as a chassis, but it was quickly discarded. We found our chassis in <i>E.coli</i> Nissle 1917 (Hancock, 2010). It is non-pathogenic, and unlike <i>P.aeruginosa</i> it does not require a shuttle vector. However, the cells were not readily available, and had to be extracted from <i>Mutaflor</i> Tablets. We selected for the desired cells using MacConkey's agar </p> |

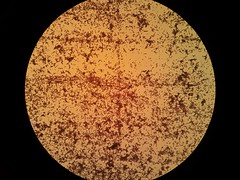

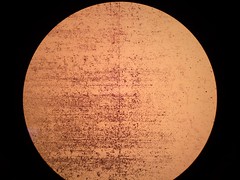

<p>To prove biofilm formation glass slides were put into 50ml tubes containing 20ml of LB broth. The LB covered around a third of the glass slide, this is the area where the biofilm would form. The LB was then inoculated with 20μl of fresh overnight culture of <i>E. coli</i> Nissle. These tubes were then left on a bench top shaker at room temperature for 24 and 48 hours. The glass slides were then removed and the biofilm was stained by standard gram stain method. Photographs were taked of the stained biofilms.</p> | <p>To prove biofilm formation glass slides were put into 50ml tubes containing 20ml of LB broth. The LB covered around a third of the glass slide, this is the area where the biofilm would form. The LB was then inoculated with 20μl of fresh overnight culture of <i>E. coli</i> Nissle. These tubes were then left on a bench top shaker at room temperature for 24 and 48 hours. The glass slides were then removed and the biofilm was stained by standard gram stain method. Photographs were taked of the stained biofilms.</p> | ||

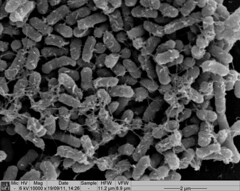

<p>Biofilm formation was also confirmed by SEM pictures that showed the extracellular matrix, such as Picture 1 below.</p> | <p>Biofilm formation was also confirmed by SEM pictures that showed the extracellular matrix, such as Picture 1 below.</p> | ||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

<p> After all of the above had been achieved, it was decided to make <i>E.coli</i> Nissle 1917 available to the Registry as a novel chassis for use in reseach and future projects involving biofilms.</p> | <p> After all of the above had been achieved, it was decided to make <i>E.coli</i> Nissle 1917 available to the Registry as a novel chassis for use in reseach and future projects involving biofilms.</p> | ||

<p> Unfortunately we were unable to transform the Nissle cells with our novel biobricks due to time constraints, and were therefore unable to operate our synthetic system within the biofilm.</p> | <p> Unfortunately we were unable to transform the Nissle cells with our novel biobricks due to time constraints, and were therefore unable to operate our synthetic system within the biofilm.</p> | ||

| + | <h4>Reference</h4> | ||

| + | <p>Hancock, V., Dahl, M. & Klemm, P., 2010. Probiotic <i>Escherichia coli</i> strain Nissle 1917 outcompetes intestinal pathogens during biofilm formation.Journal of Medical Microbiology. Vol 59, Jan 2010 pp 392-399. </p> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Revision as of 17:37, 21 September 2011

Results

Aims

-To find a transformable, biofilm forming chassis -To prove that E.coli Nissle form biofilms -To prove that E.coli Nissle are transformable with standard methods -To prove that E.coli Nissle are transformable with standard E.coli biobricks and can express them -To make E.coli Nissle available as a chassis to the Registry of Standard Biological Parts should the above be achieved -To transform our novel biobricks into E.coli Nissle and express them -To operate our entire synthetic system within E.coli Nissle biofilm

Methods

Since our project was to examine the dispersal or fixation of a biofilm, we were in need of a chassis that had the ability to form them. Originally Pseudomonas aeruginosa was considered as a chassis, but it was quickly discarded. We found our chassis in E.coli Nissle 1917 (Hancock, 2010). It is non-pathogenic, and unlike P.aeruginosa it does not require a shuttle vector. However, the cells were not readily available, and had to be extracted from Mutaflor Tablets. We selected for the desired cells using MacConkey's agar

To prove biofilm formation glass slides were put into 50ml tubes containing 20ml of LB broth. The LB covered around a third of the glass slide, this is the area where the biofilm would form. The LB was then inoculated with 20μl of fresh overnight culture of E. coli Nissle. These tubes were then left on a bench top shaker at room temperature for 24 and 48 hours. The glass slides were then removed and the biofilm was stained by standard gram stain method. Photographs were taked of the stained biofilms.

Biofilm formation was also confirmed by SEM pictures that showed the extracellular matrix, such as Picture 1 below.

Picture 1: SEM image of Nissle biofilm showing the extracellular matrix |

Picture 2: 400x A gram-stained 16-hour E.coli Nissle biofilm |

Picture 3: 100x A gram stained 16-hour E.coli Nissle biofilm |

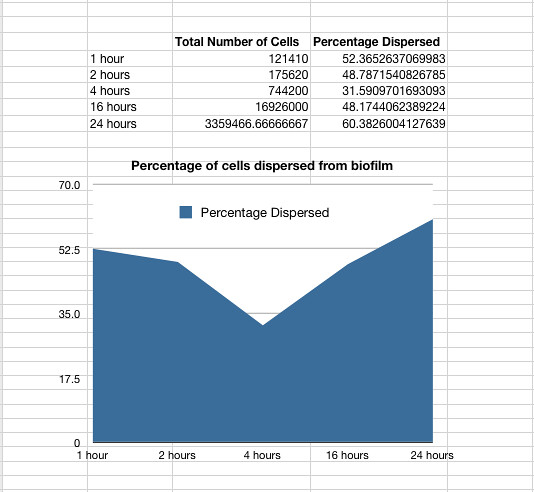

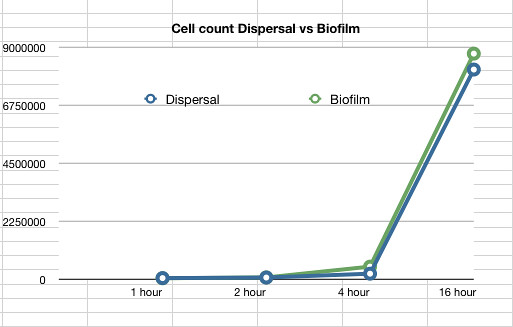

Once it had been shown that E.coli Nissle formed biofilms, a time series of biofilm formation was performed. The tubes containing the slides were left on the tabletop shaker for a set amount of time (time points ranged from 1hr to 24hrs). After the biofilm had grown its alloted time the glass slide was carefully removed and placed into a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB (which completely covered the biofilm) and left to allow the bacteria to disperse for 1hr. The slide was then transferred to a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB. The biofilm is scraped off using a spatula, and the resulting culture was vortexed for 1 minute to break up any residual chunks of biofilm. The culture containing the dispersed cells and the culture containing the broken-up biofilm were then plated in serial dilution to obtain an estimate of the number of cells in each culture. The results are shown below.

Graph 1: The total percentage of cells dispersed when a biofilm is transferred into new media vs time in hours

The data also showed that over time the amount of cells firmly within a biofilm increases at a similar rate to those that disperse and are not attached to the biofilm.

Graph 2: The estimated number of dispersed cells compared to the number of biofilm cells vs time in hours

Chemically and Electrically competent E. coli Nissle cells were made and successfully transformed with RFP. Electroporation was notably more efficient than any chemical transformation. Problems were caused by the cells' tendency to clump together, which we assume is caused by their long fimbriae that were visible on the SEM pictures. this problem can be countered by either vortexing or sonicating the culture before plating them. We expect sonication to be the more efficient method.

The transformed E.coli Nissle cells showed expression of RFP, in culture and within a biofilm, proving that they can express standard E.coli constructs. The results can be seen in Pictures 4 through 6 below.

Picture 4: RFP transformed E.coli Nissle overnight culture |

Picture 5: A 24-hour biofilm of RFP E.coli Nissle |

Picture 6: Streaked RFP transformed E.coli Nissle |

After all of the above had been achieved, it was decided to make E.coli Nissle 1917 available to the Registry as a novel chassis for use in reseach and future projects involving biofilms.

Unfortunately we were unable to transform the Nissle cells with our novel biobricks due to time constraints, and were therefore unable to operate our synthetic system within the biofilm.

Reference

Hancock, V., Dahl, M. & Klemm, P., 2010. Probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 outcompetes intestinal pathogens during biofilm formation.Journal of Medical Microbiology. Vol 59, Jan 2010 pp 392-399.

"

"