Team:NYMU-Taipei/modelling-protein-structure-champ-design

From 2011.igem.org

What is the CHAMP Design

CHAMP, the computed helical anti-membrane protein, is designed by one of the computational and genetic methods available to engineer antibody-like molecules that target the water-soluble regions of tansmembrane (TM) proteins (Hang Yin, et al., 2007).

Why We Use the CHAMP Design

The general purpose of CHAMP design is that though Transmembrane (TM) helices usually play essential roles in biological processes, companion methods to target the TM regions are lacking. The CHAMP design of TM helices that specifically recognize membrane proteins would advance the understanding of sequence-specific recognition in membranes and simultaneously would provide new approaches to modulate protein-protein interactions in membranes (Hang Yin, et al., 2007).

Now we want to let the CHAMP design play a pivotal role in our project to modulate the protein-protein interactions in membranes. But why is the CHAMP design so important in our iGEM project this year? In this year's Optomagnetic design, we want to use the designed peptide, CHAMP sequence, to inhibit the tight interaction between the two helices of membrane protein Mms13. Then we can successfully use mechanical force to change the conformation of Mms13 to induce the BiFC-based BRET phenomenon. If we do not have the target peptides, CHAMP, the two helices of Mms13 would tightly "stick" together and we can predict the results easily by the fundamental knowledge of physics that the magnetic force applied to the bacteria would not make any change to the conformation of Mms13 protein. If the two helices of Mms13 have tight interaction all the time, the wobbling light we expect in our project derived from BiFC-based BRET would not be excited. As the consequence of lacking the modulation of CHAMP, we would not get our final wobbling fluorescence but the constant light derived from a luciferase reaction; which means that we can only “turn on” neurons with constant light while the wobbling system can excite or inhibit the neurons for both “on and off” functions.

How to Design the CHAMP Peptides

We followed the design protocols in the paper- Supporting Online Material for Computational Design of Peptides That Target Transmembrane Helices (Hang Yin, et al., 2007) and Understanding Membrane Proteins. How to Design Inhibitors of Transmembrane Protein–Protein Interactions (J.S. Slusky, et al., 2009). However, because of the limited resources, we made little adjustments by using different programs, such as TMhit (Lo A., et al., 2009), ProtMod (Godzik A., et al., 2011), YASARA (Krieger E., et al., 2011), VMD (Klaus Schulten., et al., 2011), ΔG prediction server v1.0 (Hessa, T., et al., 2007) to finalize our CHAMP design. The study by Interaction and conformational dynamics of membrane-spanning protein helices (D Langosch, et al., 2009) and Helix-helix interaction patterns in membrane proteins (D Langosch, et al., 2010) gave us more knowledge about protein-protein interactions in transmembrane domains, and helped us during the CHAMP designing process.

Membrane peptide design

Transmembrane helical peptides can bind to targets with high specificity and affinity has been designed de novo (Hang Yin, et al., 2007). The method consists of four steps:

- Selection of a helical-pair structural motif based on sequence;

- Selection of a nativelike helical-pair backbone within the chosen structural motif;

- Threading the sequence of the targeted TM helix onto one of the two helices of the selected pair;

- Selection of the amino acid sequence of the designed peptide helix with a side chain repacking algorithm.

Our design based on these steps will be shown in the following sections.

Selection of a helical-pair structural motif based on sequence

Determining the domains of Mms13's amino acid sequence

The full sequence of Mms13 is (A.A.)

MPFHLAPYLAKSVPGVGVLGALVGGAAALAKNVRLLKEKRITNTEAAIDTGKETVGAGLATALSAVAATAVGGGLVVSLGTALVAGVAAKYAWDRGVDLVEKELNRGKAANGASDEDILRDELA.

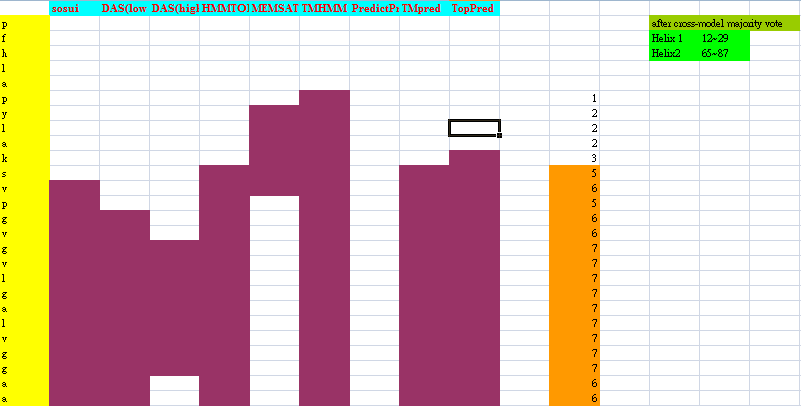

Because Mms13's structure is not 100% defined and known. We used several online prediction programs to specify the domains of Mms13 using amino acid sequences. We used sosui (Mitaku S., et al., 2002), DAS(low cut-off) (M. Cserzo, et al., 1997), DAS(high cut-off) (M. Cserzo, et al., 1997), TMHMM (Krogh A., et al., 2001), PredictProtein (Laszlo Kajan, et al., 2011), TMpred (K. Hofmann, et al., 1993), HMMTOP (G.E Tusnády, et al., 2001), MEMSAT-SVM (Nugent, T., et al., 2009), TopPred (Gunnar von Heijne, 1992). We then merged all the results using the cross-model majority vote to determine the boundaries of the two helices of Mms13.

Helix 1:a.a.12~29 and Helix2:a.a.65~87.

Selection of a helical-pair structural motif based on sequence

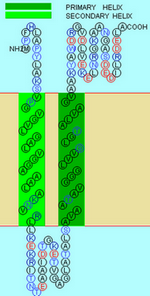

We choose the TM helix which has a G-X3-G sequence motif. The GxxxG motifs can induce the helices interaction since it leads to the formation of a flat helix surface and can maximizes van der Waal’s interactions and that the loss of side-chain entropy upon association is minimal for Gly. (William P Russ, et al., 2000) Moreover, the Gly residues in the motifs reduce the distance between the helix axes facilitating hydrogen bond formation between the Cα-hydrogens and the backbone carbonyl of the partner helix (A. Senes, et al., 2001). After searching along the helices of Mms13, we found the critical G-X3-G sequence motifs on helix1 of the Mms13 (See Figure 6).

Selection of a nativelike helical-pair backbone within the chosen structural motif

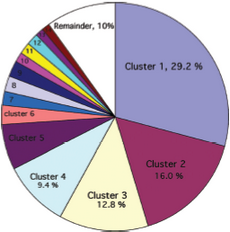

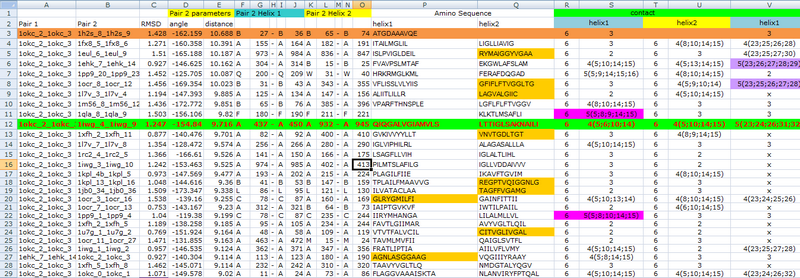

After the selection of a helical-pair structural motif, we have to select a nativelike helical-pair backbone as the templates for our CHAMP design. First, we follow the instructions to determine the template cluster. (R. F. S. Walters, et al., 2006) A library of 445 helical pairs from 31 proteins in the paper was clustered into groups based on their three-dimensional similarity. Different clusters have specific features and also show varying degrees of homogeneity. We finally choose cluster 2 as our candidates because of the antiparallel helices on Mms13 and the traits which belong to right-handed crossing angle on helix1. (For examples, the helix1 have small residues at the helix–helix interface, and they are also spaced at four-residue intervals.) The pie chart (See Figure 7) shows the fraction of the total number of pairs that fall within a given cluster and Table 1 (See Figure 8) shows some characteristics of the top 14 clusters.

After determining the cluster, we still have to choose one final template within 71 candidates in cluster 2. We first eliminate the candidates to 27 templates through the prediction of van der Waals minimum distance of the helical pairs because the final rank is based on the uniformity of packing, which was assessed by finding structures with the minimal number of inter-atomic contacts that are closer than 1.0 Å from the expected van der Waals minimum distance. (Hang Yin, et al., 2007)

Then to get the most matched template of our CHAMP design, we use the online program-TMhit (Lo A., et al., 2009) inferring helix-helix interactions from residue contact in Mms13. We select the best template pairs by finding the template which having one helix with the most residue contacts with Mms13 and whose sequence of another helix have the most residue alignments with Mms13. After comparison, we choose protein 1iwg: A437-A450 and A932-A945 as the template pairs for our CHAMP design. Part of data for comparison is shown in Figure 9).

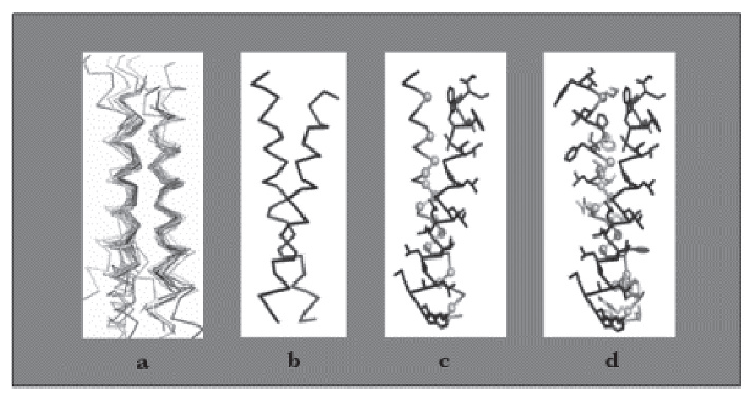

Threading the sequence of the targeted TM helix onto the selected pair

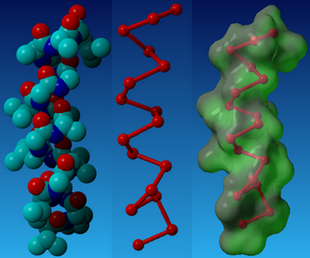

By using the online program-ProtMod-Protein Structure Modeling-Alignment (Godzik A., et al., 2011), we get the pdb file of the repacking structure, where Mms13 is aligned on the helix of the chosen template-1iwg: A437-A450.

After having both materials: the aligned Mms13 and the selected template pairs (1iwg: A437-A450; A932-A945), we threaded the Mms13 aligned sequence onto the corresponding helix. The threading process was finished by matching G-X3-G motif of Mms13 to the motif on the template structure. The backbones of the complex were then minimized to remove clashes with the threaded Mms13 sequence (See Figure 12).

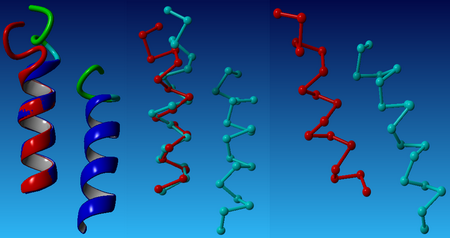

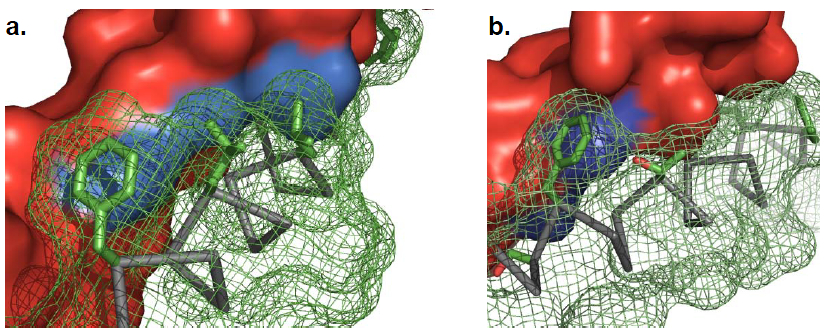

Selection of the amino acid on CHAMP design with a side chain repacking algorithm

Then, we gave a second stage repacking of the minimized structure and select the one showed a uniformly packed interior. We first find the proximal positions between Mms13 and the CHAMP template since the effect of the peripheral sequences are less dominant in the helical interaction. We use YASARA View (Krieger E., et al., 2011) to calculate the minimal inter-helical distances while using VMD (Klaus Schulten., et al., 2011) to show the hydrophobic regions, and both to specify the proximal positions between helical pairs. The results are shown in Figure 13 and 14.

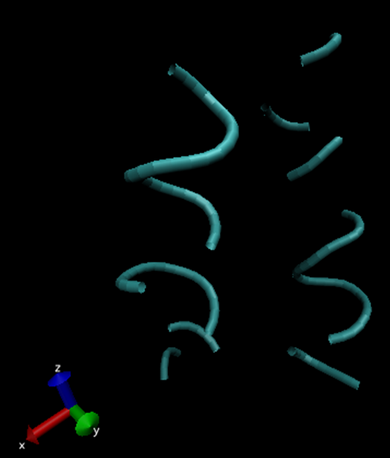

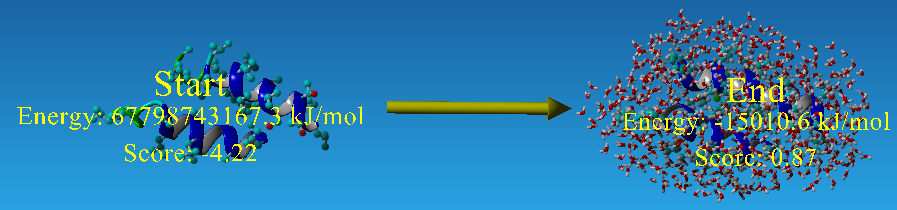

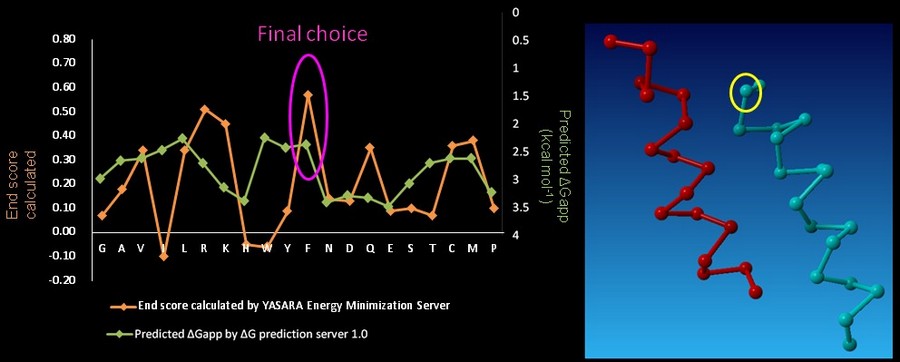

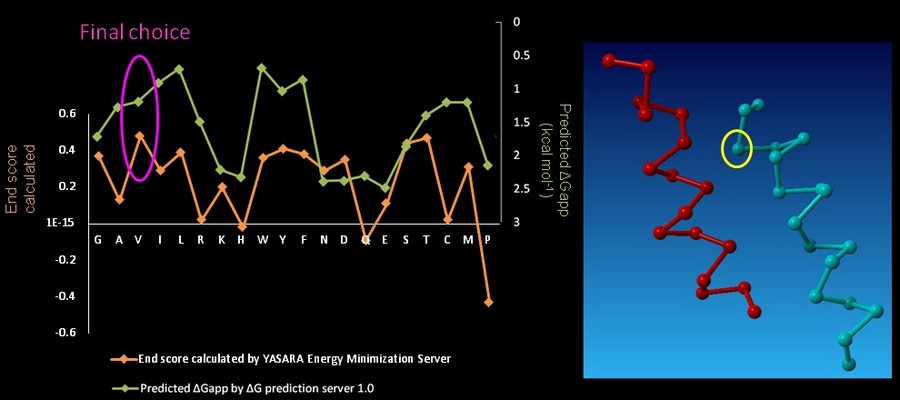

On CHAMP anti-mms13 helix, seven proximal positions were selected for secondary repacking based on their proximity to the mms13-threaded helix. We use YASARA Energy Minimization Server (Krieger E., et al., 2009) and ΔG prediction server v1.0 (Hessa, T., et al., 2007) to choose the residue sequences of proximal residues. We calculated the potentials following the potential energy functions (Hang Yin, et al., 2007) showed in Figure 15.

YASARA Energy Minimization Server (Krieger E., et al., 2009) is performed to calculate the EvdW + EHbond + Eelectrostatic + Econtact . Though the program is based on predicting the potentials in the water, we can still rank the prefer residues by using the result scores as support for our decision. The other program, ΔG prediction server v1.0 (Hessa, T., et al., 2007), in the other hand, we use it for computing the Esolvation + Eself potentials. The results of ΔG prediction server v1.0 (Hessa, T., et al., 2007) were ranked as well. By the cross-program comparison, we decided which residue is best for the corresponding proximal position.

For each step of the energy calculation process, the identity of one of the proximal positions on the CHAMP helix was mutated. (Hang Yin, et al., 2007) By using the exhaustive enumeration and the cross-program ranking strategy, we determined whether the mutation is either accepted or rejected and set the best candidate residue for the corresponding proximal position. Only the rotamers with high probabilities of occurrence within helical backbones are considered. The data for energy calculation is showed in Figure 18 and 19.

In the paper, when the identities of the proximal positions were determined, the membrane-exposed residues could then be fixed. The membrane-exposed positions are determined by random assignment of hydrophobic residues, with 60% probability given to Leu and 10% to Ala, Ile, Phe, and Val. (Hang Yin, et al., 2007) Though it could be done by random selection, we still use ΔG prediction server v1.0 (Hessa, T., et al., 2007) computing the energy to choose the CHAMP design with least energy.

The main targeting sequences of the CHAMP peptide was finally set, the last step was adding the solubilizing groups at the N- and C-termini to insert the CHAMP into the lipid membrane. We added both Lys residues to the termini of our CHAMP design. (Lys or polyethylene glycol-containing amino acids are used in the paper since the amino acids with positive charge can be driven by the negative charge of the lipid bilayer). (Hang Yin, et al., 2007) Our CHAMP design was then completed.

References

- Hang Yin, Joanna S. Slusky, Bryan W. Berger, Robin S. Walters, Gaston Vilaire, Rustem I. Litvinov, James D. Lear, Gregory A. Caputo, Joel S. Bennett, William F. DeGrado (2007). Supporting Online Material for Computational Design of Peptides That Target Transmembrane Helices. Science 315, 1817.

- J. S. Slusky, H. Yin and W. F. DeGrado (2009). Understanding Membrane Proteins. How to Design Inhibitors of Transmembrane Protein—Protein Interactions. PROTEIN ENGINEERING Nucleic Acids and Molecular Biology 22, 315-337.

- Lo A., Chiu Y.Y., Rødland E.A., Lyu P.C., Sung T.Y., and Hsu W.L. (2009) Predicting helix-helix interactions from residue contacts in membrane proteins. Bioinformatics 25, 996-1003.

- Lukasz Jaroszewski, Zhanwen Li, Xiao-hui Cai, Christoph Weber, and Adam Godzik. (2011) FFAS server: novel features and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W38–W44.

- Krieger E, Vriend G. (2002) Models@Home: distributed computing in bioinformatics using a screensaver based approach. Bioinformatics 18(2), 315-8.

- Krieger E, Koraimann G, Vriend G. (2002) Increasing the precision of comparative models with YASARA NOVA--a self-parameterizing force field. Proteins 47(3):393-402.

- Krieger E, Nabuurs SB, Vriend G. (2003) Homology modeling. Methods Biochem Anal.44:509-23.

- Krieger E, Joo K, Lee J, Lee J, Raman S, Thompson J, Tyka M, Baker D, Karplus K. (2009) Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Protein 77 Suppl 9:114-22.

- Venselaar H, Joosten RP, Vroling B, Baakman CA, Hekkelman ML, Krieger E, Vriend G. (2010) Homology modelling and spectroscopy, a never-ending love story. Eur Biophys J. 39(4):551-63.

- Joosten RP, te Beek TA, Krieger E, Hekkelman ML, Hooft RW, Schneider R, Sander C, Vriend G. (2011) A series of PDB related databases for everyday needs. Nucleic Acids Res. 39(Database issue):D411-9.

- William Humphrey, Andrew Dalke, and Klaus Schulten. (1996) VMD – Visual Molecular Dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics 14:33-38.

- R. Sharma, T. S. Huang, V. I. Pavlovic, K. Schulten, A. Dalke, J. Phillips, M. Zeller, W. Humphrey, Y. Zhao, Z. Lo, and S. Chu. (1996) Speech/gesture interface to a visual computing environment for molecular biologists. In Proceedings of 13th ICPR 96, volume 3, pp. 964-968.

- Rajeev Sharma, Michael Zeller, Vladimir I. Pavlovic, Thomas S. Huang, Zion Lo, Stephen Chu, Yunxin Zhao, James C. Phillips, and Klaus Schulten. (2000) Speech/gesture interface to a visual-computing environment. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 20:29-37.

- David J. Hardy, John E. Stone, and Klaus Schulten. Multilevel summation of electrostatic potentials using graphics processing units. Journal of Parallel Computing 35:164-177.

- Hessa, T., Meindl-Beinker, N., Bernsel, A., Kim, J., Sato, Y., Lerch, M., Lundin, C., Nilsson, I., White, SH. and von Heijne, G. (2007) Molecular code for transmembrane-helix recognition by the Sec61 translocon. Nature. 450, 1026-1030.

- Hessa, T., Kim, H., Lundin, C., Boekel, J., Andersson, H., Nilsson, I., White, SH. and von Heijne, G. (2005) Recognition of transmembrane helices by the endoplasmic reticulum translocon. Nature 433, 377-381.

- Dieter Langosch, Jana R. Herrmann, Stephanie Unterreitmeier and Angelika Fuchs. (2009) Structural Bioinformatics of Membrane Proteins- Helix-helix interaction patterns in membrane proteins.

- Dieter Langosch, Isaiah T. Arkin. (2009) Interaction and conformational dynamics of membrane-spanning protein helices. Protein Science 18: 1343–1358.

- Hirokawa T., Boon-Chieng S., and Mitaku S. (1998) SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics, 14:378-9.

- Mitaku S., Hirokawa T. (1999) Physicochemical factors for discriminating between soluble and membrane proteins: hydrophobicity of helical segments and protein length. Protein Eng. 11.

- Mitaku S., Hirokawa T., and Tsuji T. (2002) Amphiphilicity index of polar amino acids as an aid in the characterization of amino acid preference at membrane-water interfaces. Bioinformatics, 18:608-16.

- M. Cserzo, E. Wallin, I. Simon, G. von Heijne and A. (1997) Elofsson: Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in procariotic membrane proteins: the Dense Alignment Surface method. Prot. Eng. vol. 10, no. 6: 673-676.

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 305(3):567-80.

- Laszlo Kajan, Yachdav, G., Burkhard, R. (2011). High-throughput protein feature prediction in the cloud. Bioinformatics (submitted).

- K. Hofmann & W. Stoffel. (1993)TMbase - A database of membrane spanning proteins segments. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler:374,166.

- G.E Tusnády and I. Simon (2001) The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics 17:849-850.

- Nugent, T. & Jones, D.T. (2009) Transmembrane protein topology prediction using support vector machines. BMC Bioinformatics. 10:159. Epub.

- Jones DT. (2007) Improving the accuracy of transmembrane protein topology prediction using evolutionary information. Bioinformatics. 23: 538-544.

- Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. (1994) A Model Recognition Approach to the Prediction of All-Helical Membrane Protein Structure and Topology. Biochem. 33: 3038-3049.

- Gunnar von Heijne. (1992) Membrane Protein Structure Prediction, Hydrophobicity Analysis and the Positive-inside Rule. J. Mol. Biol. 225:487-494.

- William P Russ, Donald M Engelman. (2000) The GxxxG motif: A framework for transmembrane helix-helix association. Journal of Molecular Biology 296, Issue 3: 911-919

- Alessandro Senes, Iban Ubarretxena-Belandia, and Donald M. Engelman. (2001) The Cα—H⋅⋅⋅O hydrogen bond: A determinant of stability and specificity in transmembrane helix interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.31; 98(16): 9056–9061.

- R. F. S. Walters and W. F. DeGrado. (2006) Helix-packing motifs in membrane proteins. PNAS vol. 103 no. 37:13658-13663.

- Krieger E, Joo K, Lee J, Lee J, Raman S, Thompson J, Tyka M, Baker D, Karplus K Proteins. (2009) Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins.77 Suppl 9:114-22.

"

"