Team:Waterloo/Project

From 2011.igem.org

| You can write a background of your team here. Give us a background of your team, the members, etc. Or tell us more about something of your choosing. | File:Waterloo logo.png 200px |

|

Tell us more about your project. Give us background. Use this is the abstract of your project. Be descriptive but concise (1-2 paragraphs) | File:Waterloo team.png Your team picture |

| Team Example |

| Home | Team | Official Team Profile | Project | Parts Submitted to the Registry | Modeling | Notebook | Safety | Attributions |

|---|

Contents |

Project

The goal of Waterloo's 2011 iGEM project is to implement self-excising ribozymes (introns) as biobricks. But first, what are self-excising ribozymes? Ribozymes are ribonucleic acid (RNA) enzymes and enzymes are reaction catalysts. So ribozymes are just RNA sequences that catalyze a (trans-esterification) reaction to remove itself from the rest of the RNA sequence. Essentially these are considered introns, which are intragenic regions spliced from mRNA to produce mature RNA with a continuous exon (coding region) sequence. Self-excising introns/ribozymes consist of type I and II introns. They are considered self-splicing because they do not require proteins to intitialize the reaction. Therefore, by understanding the sequences and structure of these self-excising introns and making them useable, we can use them as tools to make other experiments easier.

Introduction

This design provides a reasonable basis to implement in vivo applications involving RNA level regulatory sequences such as recombination sites. Since recombination sites can interrupt the functional production of a protein, the incorporated ribozyme portions can remove them before the translation phase of gene expression. Functional synthetic antibodies and plants capable of producing domain-shuffled Cry toxins are possible applications. This experimental investigation is a novel tool for producing a wide variety of these compounds with a supplementary regulation step.

A Little Bit About Group I Introns

All group I introns in bacteria have presently been shown to self-splice (with few exceptions) and maintain a conserved secondary structure comprised of a paired element which uses a guanosine (GMP, GDP or GTP) cofactor. Conversely, only a small portion of group II introns have been verified as ribozymes (they are not related to group I introns) and generally have too many regulators to easily work with. It is mainly the structural similarity of these introns that designates them to group II. We will mainly be working with group I introns, such as the phage twort.ORF143.

Group I introns contain a conserved core region consisting of two helical domains (P4–P6 and P3–P7). Recent studies have demonstrated that the elements required for catalysis are mostly in the P3 to P7 domain. They are ribozymes that consecutively catalyze two trans-esterification reactions that remove themselves from the precursor RNA and ligate the flanking exons. They consist of a universally conserved core region and subgroup-specific peripheral regions, which are not essential for catalysis but are known to cause a reduction in catalytic efficiency if removed. To compensate for this, a high concentration of magnesium ions, spermidine or other chemicals that stabilize RNA structures can be added. Thus, the peripheral regions likely stabilize the structure of the conserved core region, which is essential for catalysis.

Trans-Esterification Reactions

The secondary structures, such as P6, formed by group I introns facilitates base pairing between the 5' end of the intron and the 3' end of the exon, as well as generates an internal guide sequence. Additionally, there is a pocket produced to encourage binding of the Guanosine cofactor. The Guanine nucleotide is placed on the first nucleotide of the intron. The 3'OH of Guanosine group nucleophilically attacks and cleaves the bond between the last nucleotide of the first exon and the first nucleotide of the 5' end of the intron; concurrently, trans-esterification occurs between the 3'OH and the 5'phosphorous from the 5' end of the intron. Subsequent conformational rearrangements ensure that the 3'OH of the first exon is placed in proximity of the 3' splice site. In this way, further trans-esterification reactions and splicing occurs.

Fusion Proteins

Fusion proteins are combined forms of smaller protein subunits and are normally constructed at the DNA level by ligating portions of coding regions. A simple construction of traditional fusion protein involves inserting the target gene into a region of the cloned host gene. However, the subsequent project design, in its simple construction, interrupts the cloned protein with ribozyme sequences flanking a stop codon. The method proposed deals with excision and ligation at the RNA level, therefore, the unaltered DNA sequence does not code for a functional protein.

The ligation of protein coding sequences can create functional fusion proteins for many applications including antibody or pesticide production; however, this method of production is limited to producing the same fusion protein each time since the sequence is not modified in between the transcription and translation phases of gene expression. One disadvantage of this is the resultant resistance of a pathogen to antibodies or a target organism to pesticides. For example, a specific pesticide (Cry toxin) may eventually not be effective to its target plant if subsequent plant generations inhibit its uptake, overproduce the sensitive antigen protein so that normal cellular function persists, reduce the ability of this protein to bind to the pesticide or metabolically inactivates the herbicide. Similar mechanisms contribute to antibiotic resistance. Any resistant organisms will inevitably prevail in subsequent generations. Recombination sites could potentially be incorporated into the subsequent project design to circumvent some of the difficulties with traditional fusion proteins as a result of host resistance. However, recombination sites may interrupt the functional fusion protein from forming. Ribozyme segments at the RNA regulation level can potentially remove disrupting sequence after such shuffling occurs. Therefore, the intervening sequence maintains its DNA level functionality but is removed when no longer needed at the RNA level. Fusion protein design focused on the DNA level does not have this dynamic regulation.

The Cre-Lox System

In bacteriophage P1 exists the cre enzyme and recognition sites called lox P sites. This viral recombination system functions to excise a particular DNA sequence by flanking lox P sites and introduce the cre enzyme when the target is to be excised. The cre enzyme both cuts at the lox P site and ligates the remaining sequences together. The excised DNA is then degraded. This is similar to our project design; however, instead of requiring the addition of an enzyme at the desired excision time, the self-excising nature of ribozymes automatically functions during the normal process of gene expression (RNA level).

Project Details

Experimental Design

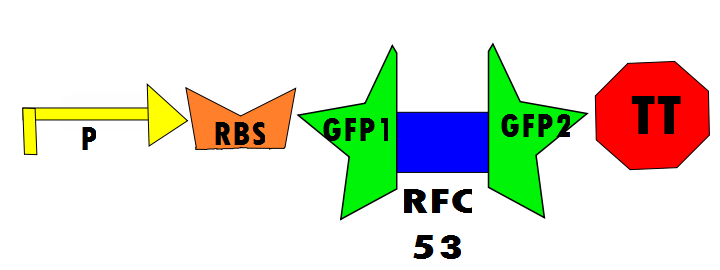

Our protocol will involves the insertion of a functional protein, split by the self-removing elements, between CUCUUAGU and AAUAAGAG in the P6 region of twort.ORF143. GFP (green fluorescent protein) is split into two parts, which will be referred to as GFP1 and GFP2. With a constitutive promoter, GFP1 and GFP2 will be separated by a class 1 A2 intron split into two (for now, IN1 and IN2) sequences that flank another sequence inserted into the P6 loop, which was chosen because anything attached to this region will remain outside the protein. Note that this experimental design also contains an in frame stop codon, which is expected to be spliced out of the sequence with IN1 and IN2 and will utilize the RFC53 convention. Following GFP2 is a transcriptional terminator (TT). The method of making this construct is detailed in RFC53.

Below is Figure 1 through Figure 3. They illustrate the order of parts in the design and the trans-esterification reaction that results in a function GFP:

Biobricks for Experimental

As per RFC 53 convention, enzyme digestions are followed in the particular order outlined below. The standard procedure makes this technique reproducible, therefore, more easily extrapolated to other applications. Compared to other protein fusion methods, this design facilitates additional regulation within necessary guidelines. However, the embedded post-transcriptional modification in this design is a complication to consider in simpler designs where regulation at this level is not necessary. As such, unnecessary bulk in plasmid vectors is known to add to metabolic load.

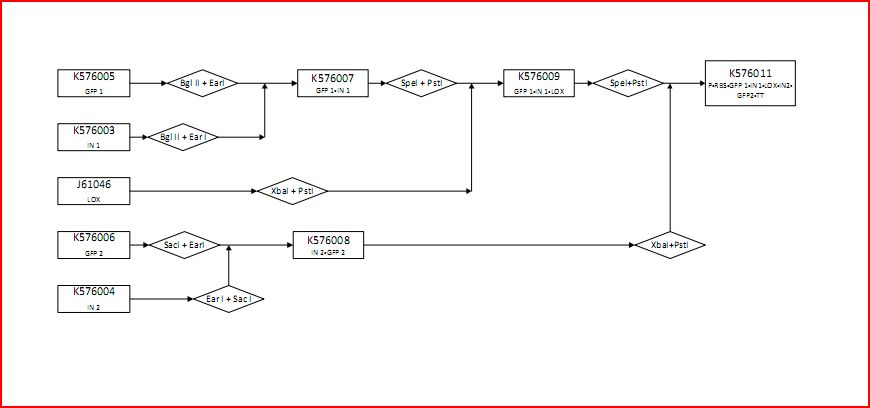

The following figure graphically shows the laboratory procedure for the experimental design in the form of an enzyme map:

- K576005 contains the first component of GFP (GFP1)

- K576003 contains the first part of the intron sequence (IN1)

- J61046 contains the lox site

- K576006 contains the second component of GFP (GFP2)

- K576004 contains the second part of the intron sequence (IN2)

- K576007 contains GFP1 and IN1

- K576009 contains GFP1, IN1 and lox1

- K576011 contains the promoter (P), ribosomal binding site (RBS), GFP1, IN1, lox site, IN2, GFP2 and transcriptional terminator (TT). This is the final construct (experimental design).

Controls

Controls are necessary to prove that the design of this experimental investigation is functional and more practically for comparison of fluorescence in the laboratory. In the positive control, GFP1 and GFP2 flank either RFC25 or RFC53, which will not disrupt translation regardless of the linker. Therefore, fluorescence is expected. The experimental run will ideally show fluorescence resulting from the self-excision of IN1 and IN2.

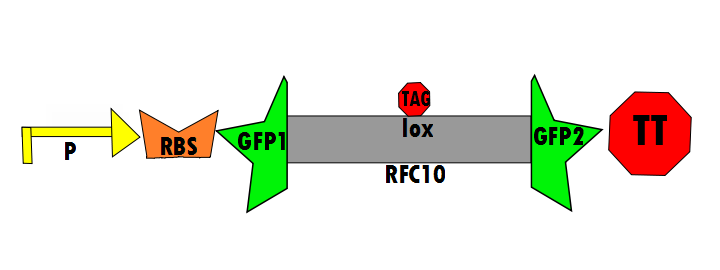

In the negative control (using the same constitutive promoter), GFP1 and GFP2, followed by a transcriptional terminator, flank RFC10 (Request For Comments) resulting in a stop-codon-containing scar. No fluorescence is expected for this component (background) because translation is interrupted. This is meant to control for the possibility of a non functional fusion protein. The expectation is that this fusion of GFP1 and GFP2 will not fluoresce, which is a consequence of some fusion protein techniques. Figure 6 shown below details the negative control design:

Biobricks for Controls

Figure 7 graphically shows the laboratory procedure for the control designs in the form of an enzyme map:

- K576005 contains the first component of GFP (GFP1)

- K576006 contains the second component of GFP (GFP2)

- K576013 contains the promoter (P), ribosomal binding site (RBS), GFP and transcriptional terminator (TT). This is the positive control.

- K576005 contains the first component of GFP (GFP1)

- J61046 contains the lox site

- K576006 contains the second component of GFP (GFP2)

- K576012 contains the promoter (P), ribosomal binding site (RBS), GFP1, lox site, GFP2 and transcriptional terminator (TT). This is the negative control.

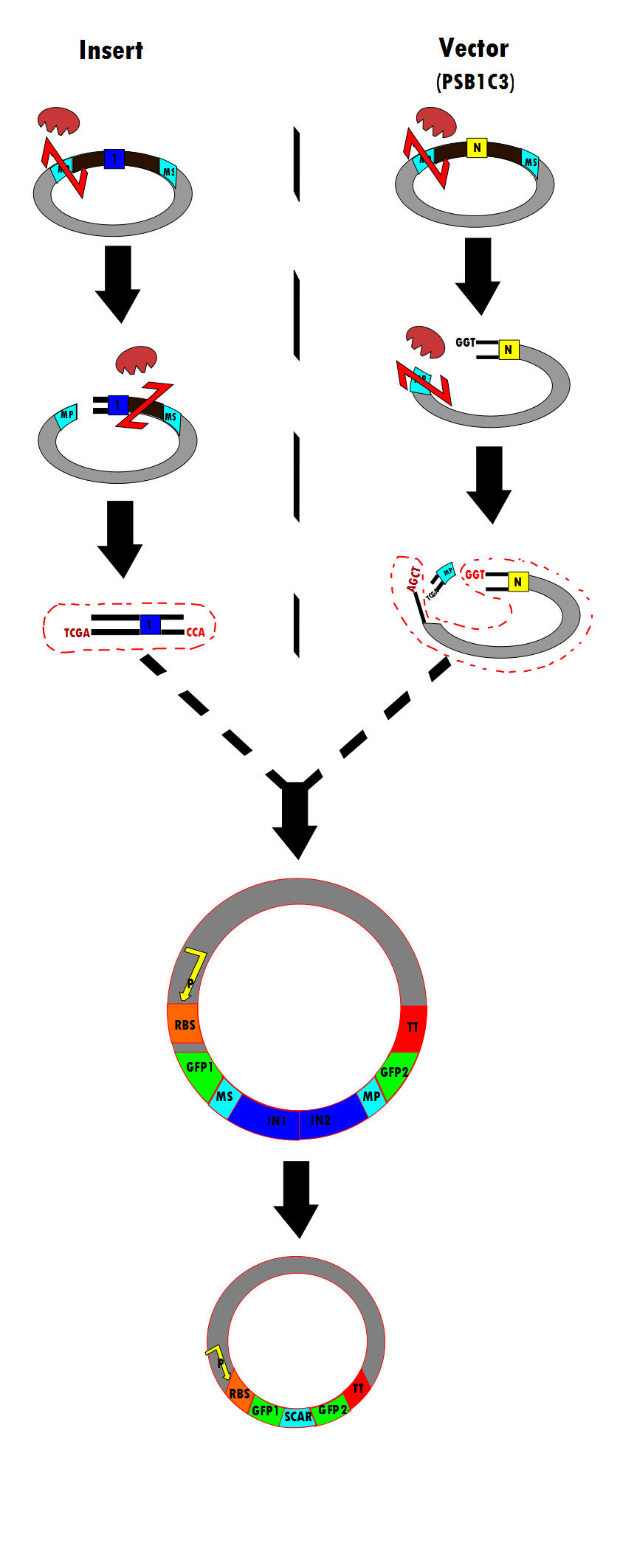

Making the Construct with RFC53

Figure 8 is a flow chart of the general work flow involved in the construction of our experimental plasmid, as per RFC53 conventions.

- (1) The insert is isolated through a series of enzyme digestions. One intron (in blue) is shown here as a representation. The insert is isolated for subsequent ligation.

- (2) Similarly, the pSB1C3 vector is isolated through enzyme digestion. Note that "N" indicates that this is the vector portion. The vector is also isolated for the ligation step. It must be noted that pSB1C3 vector contains a cu site of SacI, an enzyme that is used in RFC 53. BBa_K371053 resolves this issue by mutating the cut site of SacI.

- (3) The two components (insert and vector) are ligated together to produce the final construct.

- (4) According to the experimental design, the final construct will contain self-excising ribozymes, which in the last step result in a non-disruptive ligation scar and, therefore, the expression of GFP.

Preliminary Testing

Although completion of a preliminary version of the final construct was achieved, lack of GFP fluorescence proved suspicion of questionable band placements during second and third stage electrophoresis. Final diagnostic digestion reaction confirmed abnormalities from designed constructs. Testing via digestion was completed for every intermediate, control and final constructs. Consequently, BBa_K576003, K576004, K576005, and K576006 were the only parts able to be confirmed. All the other intermediates and constructs have questionable band location which disrupted final construct fluorescence.

The above electrophoresis picture describes the resultant bands from the diagnostic digestion. Although bands 5, 6 and 7 (sub clones) have been confirmed, the adjacent positive control (band 8) and all GFP and intron digestions are not consistent with the expected patterns. The GFP-INT and GFP-INT-lox constructions (bands 9, 10 and 11) have been verified as inaccurate. The questionable placements of these bands indicate that the cut sites, thus the fragment length and containing sequence, do not match the planned construction. Therefore, it is not likely that they contain functional GFP, introns or lox, which would result in a lack of fluorescence in the final stage of construction. Further testing to reconstruct the contaminated clones is necessary for the functional final product; however, lab work has stopped due to time constraint. A diagnostic digestion at each step is recommended to circumvent any similar issues upon the continuation of this project.

"

"