Team:Edinburgh/Phage Reactors 1.0

From 2011.igem.org

Update: Version 2.0 of this page now exists.

Contents |

Overview

There exist situations where:

- several enzymes are needed to produce the desired product

- these enzymes work synergistically

- these enzymes must work outside the cell

This proposal allows for the construction of scaffolds containing several enzymes, as well as ensuring that this complex is exported from the cell. This is accomplished by using phage as the scaffold, and attaching enzymes to it by protein fusion.

There are probably many uses of an external reaction scaffold, so this technique is fairly general and could hopefully be used for many purposes, just by swapping in the correct BioBricks. One example is a cellulosome, which is a complex of cellulolytic enzymes that can be used to turn cellulose (tough plant material) into sugar, which can then be fermented into fuel. This is something Chris is quite expert on, so could be a good fit for the lab.

Technical notes

The project would probably use phage M13, which is non-lytic (does not kill the bacteria). The major coat protein (p8 aka pVIII) already exists in the Registry as <partinfo>BBa_M13008</partinfo>, although DNA is not available. The entire genome is known (e.g. here is the entire M13KO7 genome) so primers can be designed. New England Bioworks claims:

- "The major coat protein pVIII is present at ~2700 copies per virion, of which ~10% can be reliably fused to peptides or proteins."

Ideally, we wouldn't have to work with infectious phage at all. Apparently, if M13 lacks a viable pIII protein it is non-infectious (so claim Cebe and Geiser, 2000).

Interestingly, MIT 2010 made use of the fact (from Rakonjaca and Model, 1998) that if pIII is deleted, very long phage particles will be formed and tethered to the membrane; this may be acceptable or even positive, if it anchors the bacteria to the substrate it's meant to use.

Phage itself can be ordered if needed, e.g. here. MIT 2010 used a phagemid with a pIII deletion, available from Progen Biotechnik (called hyperphage).

We should be able to manufacture our own phagemids using <partinfo>BBa_K314110</partinfo>, which is known to work! (A phagemid is a plasmid that contains both a plasmid-type origin of replication, but also a phage-type rolling circle origin so it can form single stranded DNA which is packaged into the phage capsid. The <partinfo>BBa_K314110</partinfo> part is exactly that: a phage-type rolling circle origin.)

Proteins can be fused to pVIII at its amino terminal (i.e. 5' end in the DNA), according to Weiss and Sidhu, 2000.

To attach several different proteins to the resulting phage, different fusions can be created and all of them expressed on a plasmid. It may be simplest if this is a different plasmid from the phagemid, though plasmid compatibility will have to be kept in mind.

Chris notes that the presence of repeated sequences on a plasmid can lead to genetic instability, but this will not be a problem in lab strains, which lack an important recombination enzyme. As for the use of this technology in industry, it will be possible to overcome this problem simply by synthesising coding sequences with as many altered (but synonymous) codons as possible. The (non-iGEM?) group MIT 20.109 Spring07 seem to have thought along these lines, e.g. compare <partinfo>BBa_M13008</partinfo> with <partinfo>BBa_M31281</partinfo>.

(An alternative is just to attach different enzymes to different coat proteins; pIII is known to work; maybe one of the other coat proteins as well...)

One thing to bear in mind is that the expression levels will need tuning; we need to make enough fusion proteins that some of them get onto the phage coat, but not so many as to gum up the works entirely.

Problems

- Because M13 is not lytic, the pVIII protein includes a Sec leader sequence which it uses to get to the bacterial membrane. Our fusion would need to get to the membrane somehow as well.

- The pVIII mature protein is fairly small (50 residues) so whatever we fuse to it will dwarf it. It may not be able to get through the membrane channel that M13 creates. This may be a fatal problem; the literature seems to take a dim view of attaching large proteins to pVIII, e.g. Sidhu et al (2000) say "In our experience, most large proteins display well below one copy per phage particle."

- It seems fusion to pIII works better, but there are only 5 copies of that on the phage, which sort of defeats the whole purpose...

- Can these problems be solved by other techniques or with other phage?

- T7 is lytic so does not need Sec, but it is claimed to be able to carry only 0.1 to 1 large protein per phage...

- It may be easier to fuse stuff to pIII but there are only five copies per phage.

- Thammawong et al (2006) report using the Tat pathway to get a (385 aa?) protein attached to M13 via pVIII.

- It may be possible to make pVIII with a small "zipper" protein attached to it; we can then attach another zipper to the protein of interest (i.e. the cellulase) and export it to the periplasm by whatever means necessary. The two will join together in the periplasm, and so will not need to pass through the membrane together. MIT 2010 seem to have accomplished the first step. The basic idea is similar to that of Paschke and Höhne (2005) (see Figure 1) and Wang et al (2010).

- Actually, this might be impossible if the phage exit channel blocks the protein of interest from interacting with pVIII. Does it?

- Currently the Tat solution or the "zipper" solution look the most promising but there is no doubt that complete failure is a possibility.

An example complete system

A complete system could contain:

- A plasmid, chloramphenicol resistant, probably pSB1C3, with:

- An f1 origin of replication, namely <partinfo>BBa_K314110</partinfo> (this is probably optional, but see below for rationale)

- Fusions of relevant proteins with Tat signals to mature pVIII, e.g.:

- Promoter-RBS-Tat-Endoglucanase-pVIII (based on <partinfo>BBa_K392006</partinfo>)

- Promoter-RBS-Tat-Exoglucanase-pVIII (based on <partinfo>BBa_K392007</partinfo>)

- Promoter-RBS-Tat-β-glucosidase-pVIII (based on <partinfo>BBa_K392008</partinfo>)

- A compatible plasmid, kanamycin resistant, with:

- The entire working M13KO7 genome, but perhaps with pIII deleted, maybe also the phage origin deleted?

The 2nd plasmid produces a normal phage capsid, while the 1st plasmid produces pVIII-fusions which will incorporate into it. The DNA incorporated into the capsid will mostly be from the 1st (safe, non-infectious) plasmid, because M13KO7 preferentially places DNA with an f1 origin into the capsid (according to New England Biolabs). This won't matter if we delete pIII, since in that case there is no possibility of producing infectious phage.

Alternatives

An alternative would be to have everything on one plasmid.

Another alternative would be to use BRIDGE to get the M13KO7 genome (again, perhaps minus pIII) into the E. coli chromosome, so we only have to worry about the plasmid that codes for our fusion proteins.

Two options, originality, and MIT 2010

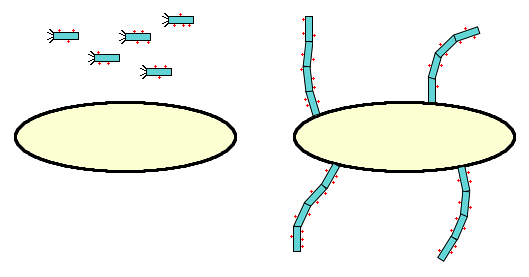

As this idea was originally conceived, it would use free-floating phage particles. Only after seeing the phage component of MIT's 2010 project did the pIII-deletion become a part of the idea.

The original idea (free phage) looks nothing like MIT's project, whereas the later version (phage tendrils) looks somewhat similar to it. However, although the techniques used are the same, the goal is very different; MIT worked to cross-link phage filaments to create a novel biomaterial, whereas we will demonstrate this technique's value for catalytic uses.

Building upon other people's work is very much in keeping with the "open-source biology" ethos of iGEM. For example, Bristol 2010 showed that it's possible to do well with an adaptation of prior work. It would be sad if every team felt they had to start from scratch. Still, if we wish to appear more original, we could go with the free phage idea.

One possibility is to do both; it should be possible to convert a tendril phenotype into a free-phage phenotype by supplying the pIII gene (i.e. <partinfo>BBa_K415138</partinfo>). This would enable comparisons so we find out which is best.

A modelling component

This project has a natural modelling component. Cellulosomes contain several different enzymes that assist in the conversion of cellolose into sugar. It would be good to optimise what the ratio of these various enzymes should be. Modelling will be needed for investigation of other possible phage reactors as well.

Also, since both wildtype and modified pVIII proteins are being produced, we will want to choose what that ratio is as well.

Vincent suggests that there are population dynamics to be modelled for the alternative system where the phage are actually infectious.

Testing

As proof of concept (i.e. something we can accomplish in a short time) perhaps it would be sufficient to get just one fusion protein working. We need to prove that the enzyme part is actually getting out of the cell, so we must demonstrate that some substance which cannot enter the cell is nevertheless being degraded.

A fairly easy test would be to use a fusion of amylase to pVIII, and assay for starch degradation, which is very easy. There is no amylase BioBrick (with DNA available) in the Registry, so we'd have to make it.

References

- Cebe R, Geiser M (2000) Size of the ligand complex between the N-terminal domain of the gene III coat protein and the non-infectious phage strongly influences the usefulness of in vitro selective infective phage technology. Biochemical Journal 352: 841-849.

- Paschke M, Höhne W (2005) A twin-arginine translocation (Tat)-mediated phage display system. Gene 350(1): 79-88 (doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.02.005).

- Rakonjaca J, Model P (1998) Roles of pIII in filamentous phage assembly. Journal of Molecular Biology 282(1): 25-41 (doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2006).

- Sidhu SS, Weiss GA, Wells JA (2000) High copy display of large proteins on phage for functional selections. Journal of Molecular Biology 296(2): 487-495 (doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3465).

- Thammawong P, Kasinrerk W, Turner RJ, Tayapiwatana C (2006) Twin-arginine signal peptide attributes effective display of CD147 to filamentous phage. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 69: 697-703 (doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0242-0).

- Wang KC, Wang X, Zhong P, Luo PP (2010) Adapter-directed display: a modular design for shuttling display on phage surfaces. Journal of Molecular Biology 395(5): 1088-1101 (doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.068).

- Weiss GA, Sidhu SS (2000) Design and evolution of artificial M13 coat proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology 300: 213-219 (doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3845).

Other useful links

- Kehoe JW, Kay BK (2005) Filamentous Phage Display in the New Millennium. Chemical Reviews 105(11): 4056-4072 (doi: 10.1021/cr000261r).

- Sidhu SS (2001) Engineering M13 for phage display. Biomolecular Engineering 18: 57-63.

- Willats WGT (2002) Phage display: practicalities and prospects. Plant Molecular Biology 50: 837-854 (doi: 10.1023/A:1021215516430).

"

"